|

Search Help |

|

Links Robert Graves Website Other RG Resources |

Critical Studies

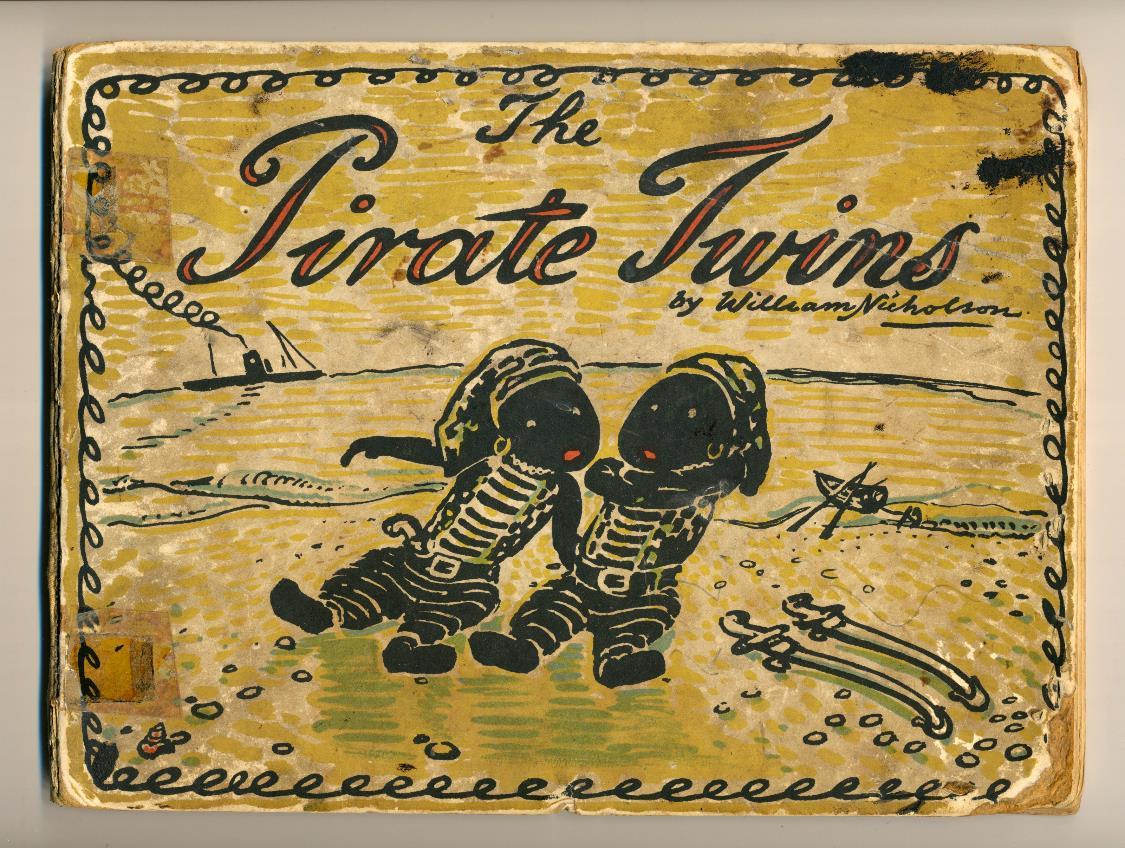

William Nicholson and the Pirate Twins

Abstract: The Pirate Twins, black sock dolls designed and created and named by Nancy Nicholson, intersect the story of her life with Robert Graves as well as that with her father, Sir William Nicholson, who used them as models for the eponymous picturebook published within a month of Good-Bye to All That. The small, but triumphant, pirates echo Nicholson’s treatment of a giant pirate in his costume designs for Peter Pan (1904); they are a characteristic, revelatory contribution to the artist’s canon.

Keywords: Robert Graves, black protagonists in children’s literature, pirates in children’s literature, modernist picturebooks

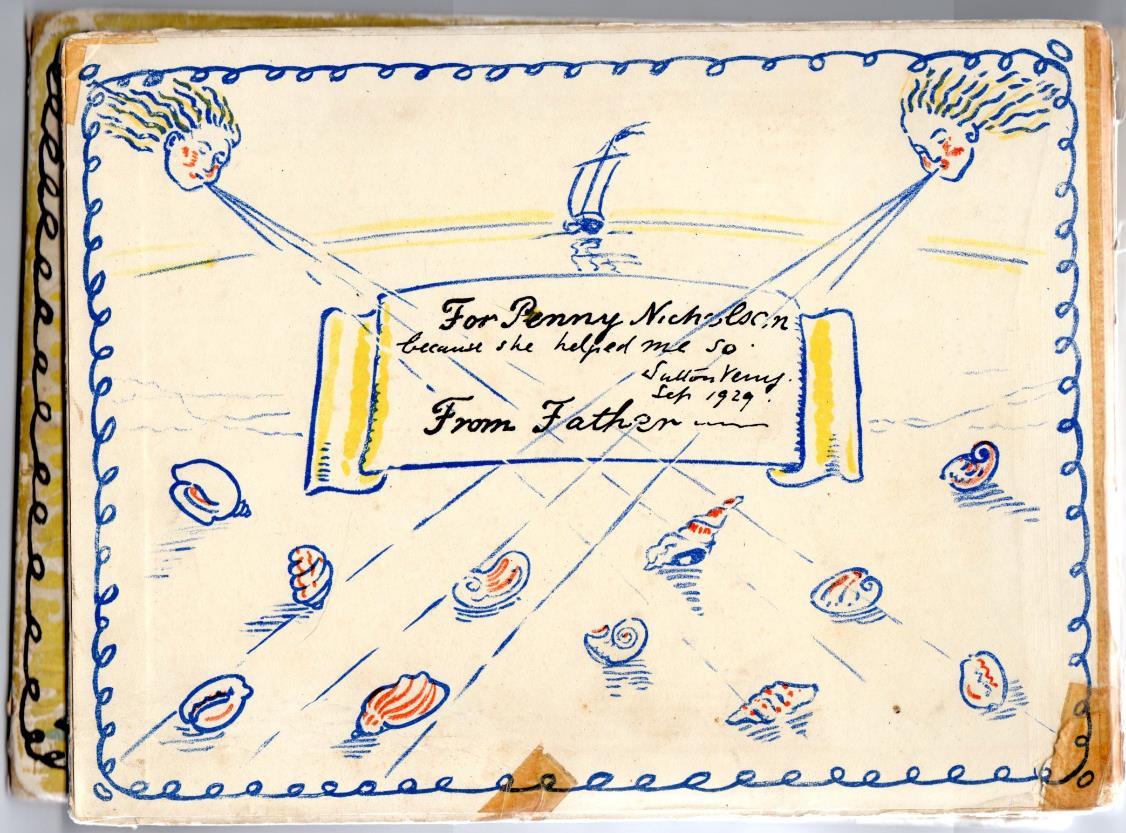

Cover of Nancy Nicholson’s copy of The Pirate Twins.

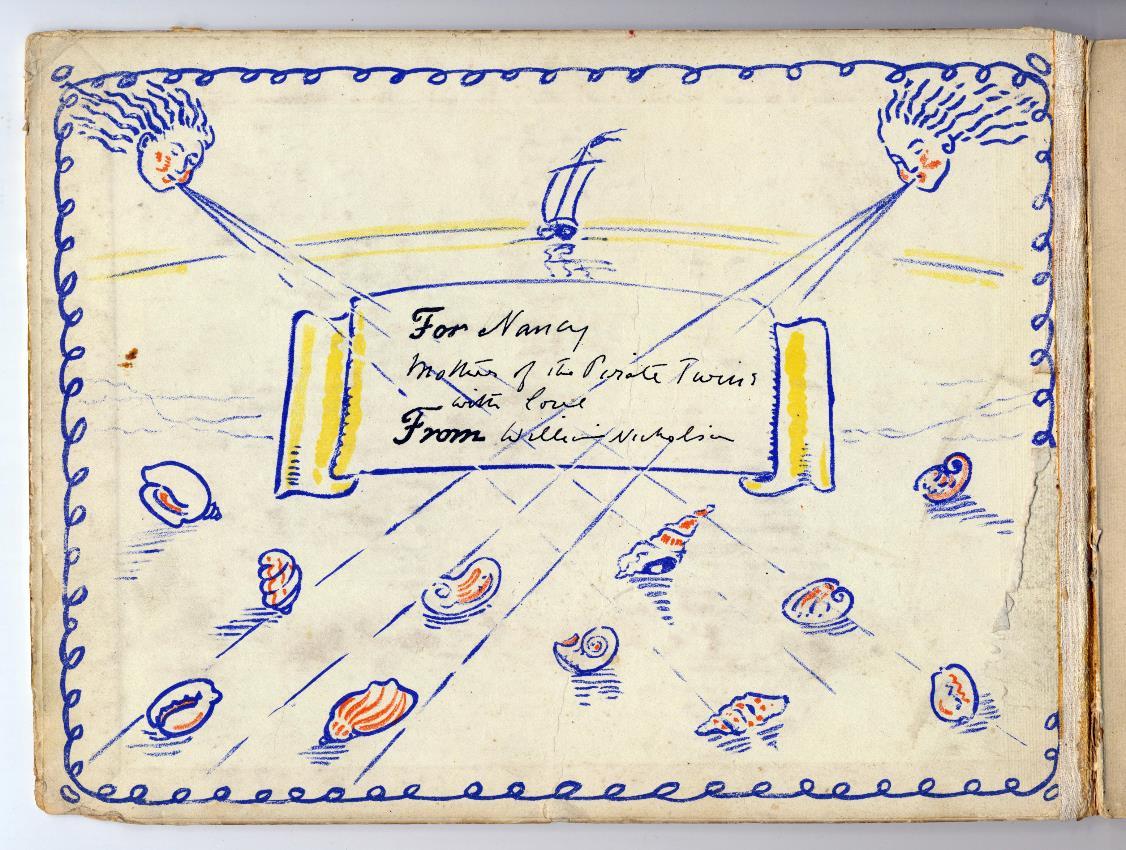

Dedication in the front of Nancy Nicholson’s copy of The Pirate Twins Permission Carola Stuart Wortley, in trust for Manuela Graves.

Pirates

The Pirate Twins (1929) by the English painter Sir William Nicholson is a milestone in children’s picturebooks.

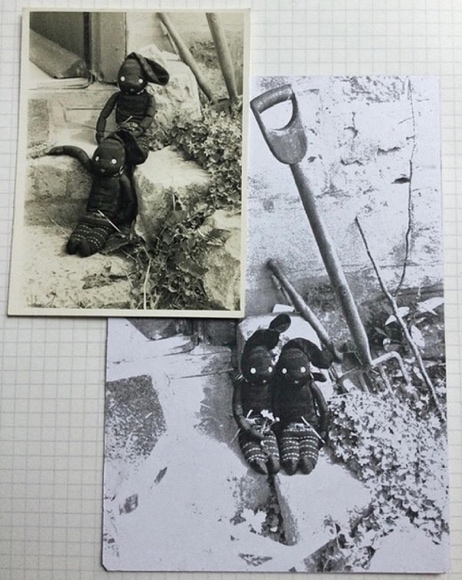

As Sam Graves noted, WN bought some black patterned socks in France and ‘had second thoughts about them’.

more. Each of the Graves/Nicholson children had a pair of them. Two of these remain, which may have belonged to Jenny Nicholson.

Photo by Nancy Nicholson of Alexander and Bartholomew, ‘Taken on Nancy’s roadside step in Ansty.’ Permission Carola Stuart Wortley, in trust for Manuela Graves.

In a July 1919 letter to his sister Rosaleen, Robert Graves appears to be discussing the pirate dolls as a potential source of much-needed income in the second year of his marriage to Nancy, a time when plans for children’s projects were being discussed. Richard Perceval Graves notes: ‘Another scheme, mentioned in the same letter, involved marketing a black gollywog doll of Nancy’s design. Examples of these dolls “went everywhere with them” at that time; and Robert asked Rosaleen to tell their father that he and Nancy were in the process of having their design patented’.

The Pirate Twins are not golliwoggs; they do not have the minstrel faces or bushy hair characteristic of the Florence Upton creation.

The Pirate Twins is taken seriously by scholars because it is an early and unusually fine example of a book in which narrative line is carried by a deft integration of the visual and literary elements and, of course, is beautifully drawn. The book contributes to Nicholson’s canon in meaningful ways because it is a legitimate extension of his artistic vision. He had chosen not to be solemn about the things that he was most serious about; the wit and playfulness of his pages was the hallmark of his defiance of the painting tradition he had inherited. He had put some of his most brilliant creative work into still lifes of food and fish, for example, which serve a narrative function in the Pirate Twins book. His oil paintings were fundamentally concerned with ‘magic’, often based upon painterly illusion or an unusual viewpoint. As his daughter Eliza noted, ‘it was as if he were training to be a magician, and we were helping him’.

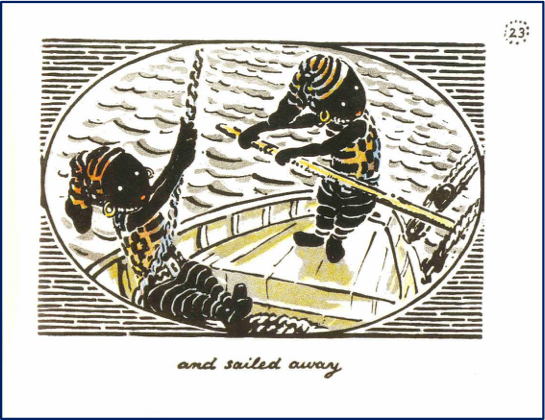

The Twins escape back to sea. Andrew Jones Art, 2005. William Nicholson’s writings and drawings ©Desmond Banks.

The Pirate Twins is an intimate book because it looks hand drawn, including the borders of the pictures and page numbers, and has no printed material in it. As Greg M. Smith notes, line drawings convey the knowledge that they are the subjective view of a single hand, and the simplicity and casual style of the book emphasize this.

Dedication in Eliza Banks’ copy from her father. She was called Penny (from Pennywort) as a child. William Nicholson’s writings and drawings ©Desmond Banks.

The little girl in The Pirate Twins, Mary, is also in Clever Bill (1926), the first of WN’s picturebooks. Eliza Banks, his younger

daughter with his second wife, Edith Stuart Wortley, explained in her essay about Clever Bill that the model for Mary in that book was RG and Nancy’s daughter Jenny (Eliza’s slightly older niece).

Jenny, David, Catherine and Sam were living with Nancy, two miles away in the next village. We quickly became a small, very active group of five, always playing together, running across the meadows visiting each other, bicycling, exploring our Wiltshire downs and woodlands.

John and Anne, Eliza’s half-brother and sister by her mother’s first marriage, were older than this group but present: their playthings also became part of Clever Bill. Eliza and Jenny both wore the sunbonnets shown in the books when they went out, and Mary’s dress was one that Nancy had made for Jenny.

But the little girls, even if present, were no longer the right size to model for Mary in 1929, and perhaps earlier memories were also playing a part. Nancy, for example, posed in a similar bonnet for a childhood portrait;

The related family background – Eliza Banks’ contention that The Pirate Twins is about her father’s life – has been the most-discussed aspect of the story.

Peter Pan and the Black Pirate

1904 drawing of the ‘Black Pirate’ costume sketch as used in the first production ofPeter Pan. Permission Karpeles Manuscript Library.

Pirates reoccur in WN’s career, but the most relevant black pirate may be one that was created when Nancy (1899-1977) was about five. WN designed the costumes for the first production of Peter Pan in 1904.

It may be that the Black Pirate, conceived of grandly, simply did not fit within the play. The two men differed widely in what they thought the play was about. Nicholson’s sketch of Peter, for example, looks like James Dean (a rebellious male adolescent), not the androgynous figure of the stage. The pirates also are differently conceived. Barrie’s pirates are meant to be a thrill, but they are also meant to be summarily vanquished as part of the self-aggrandizing fantasy of the boys. Coral Island, Treasure Island, etc. are Barrie’s sources, and this is Barrie’s resolution (Alton, pp. 379-83). This inevitable resolution means that a pirate such as the Black Pirate, whose giant size is most of his identity within the script, will be undermined within this play. It is easy to see as comic a sword fight between a giant man and a child hardly reaching his waist that ends in the child winning.

But Nicholson’s favourite author in boyhood and young manhood was Alexandre Dumas.

The flames of the Leicester grew thicker and thicker. Tongues of fire flickered out of her portholes; climbed her masts; devoured her sails.

The loaded guns burst, one by one. Then, all at once, there was a deafening explosion. The body of the ship split, and a geyser of flame shot skyward. The observers watched fragments of masts and riggings hurtle through the air and plunge into the sea. Of the Leicester, nothing remained but debris.

And Georges gets the girl. Winning pirates are what the Pirate Twins are, too, and they win in a plot very like that of Peter Pan – only, of course, the Twins are Peter.

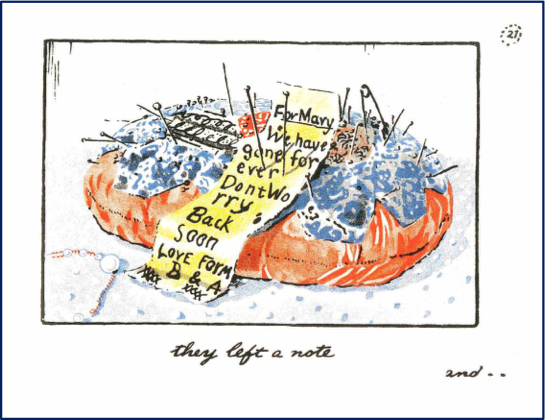

The Pirate Twins’ farewell note, using the initials of Alexander and Bartholomew. Andrew Jones Art, 2005. William Nicholson’s writings and drawings ©Desmond Banks.

The Pirate Twins (and ‘Trips’)

Good-Bye to All That (1929) includes an anecdote from 1918 that quotes Robbie Ross as telling RG that he should not marry Nancy Nicholson because ‘there was negro blood in the Nicholson family, that it was possible that one of Nancy’s and my children might revert to coal-black’.

Faber and Faber 1929 edition, with WN’s addition of a third Pirate (in the bathtub) for ‘The Pirate Trips’ [see below]. William Nicholson’s writings and drawings ©Desmond Banks.

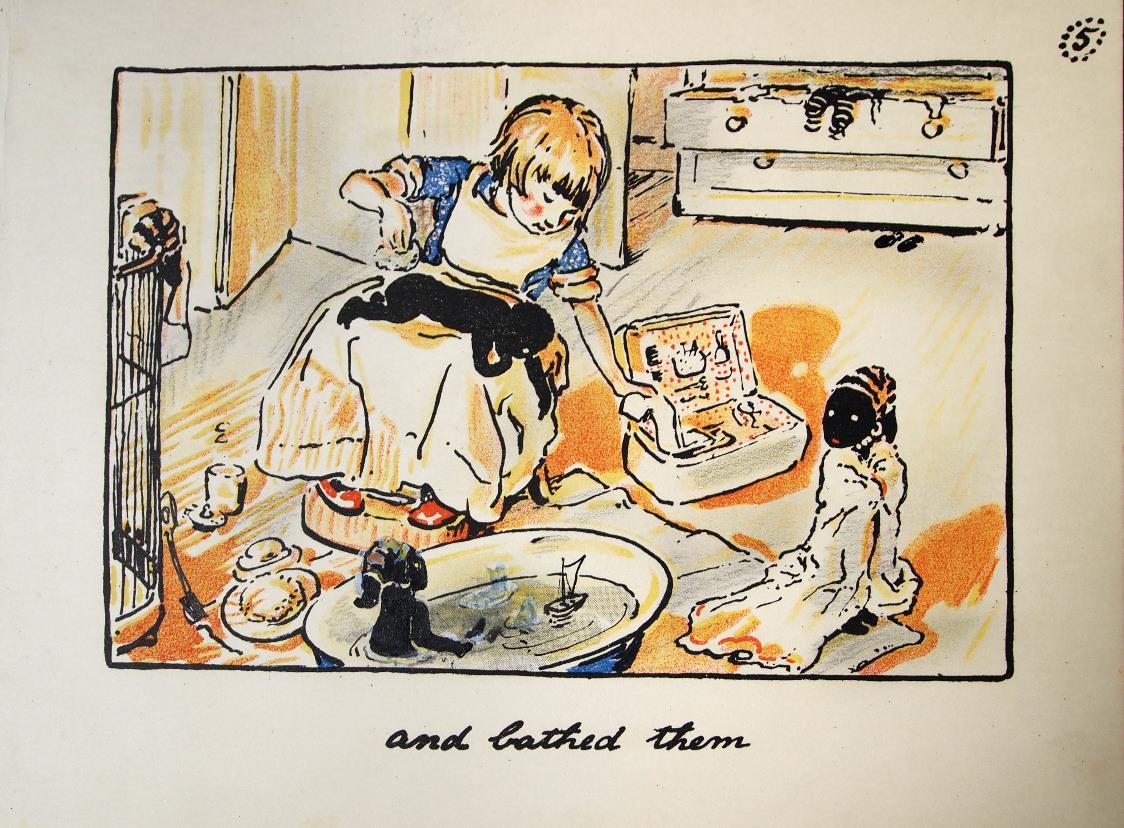

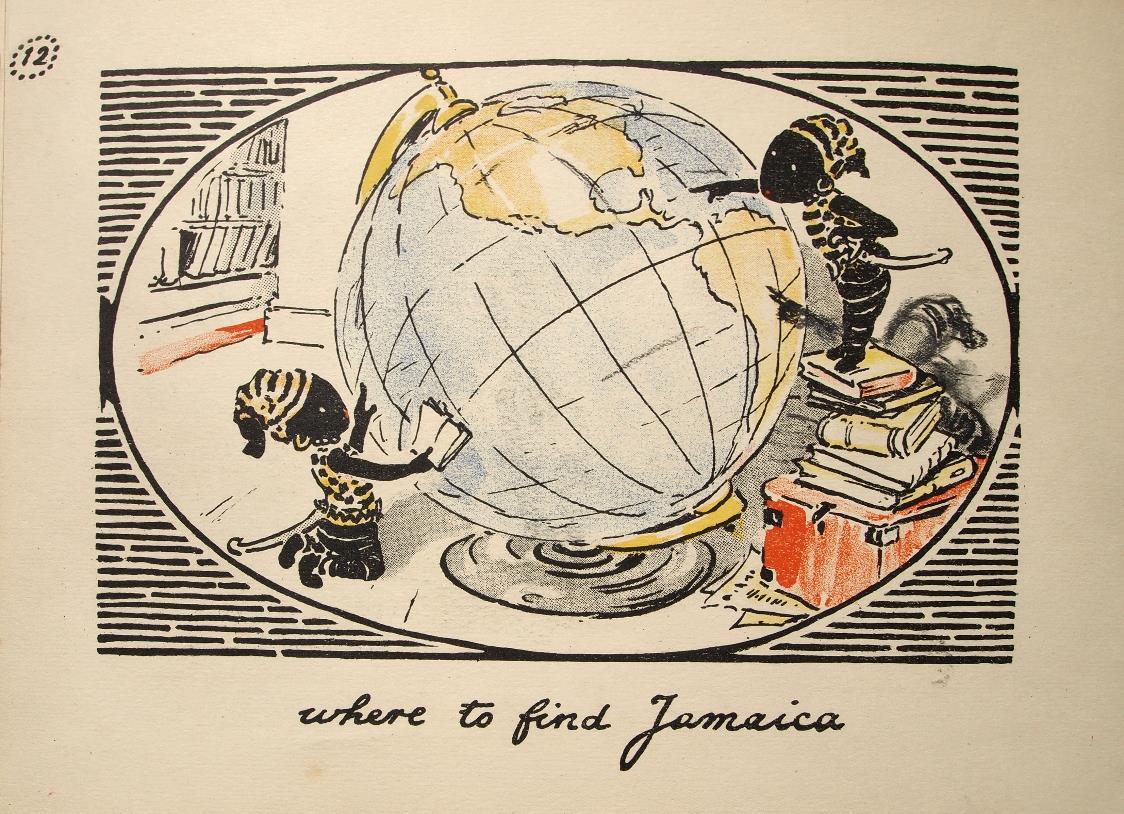

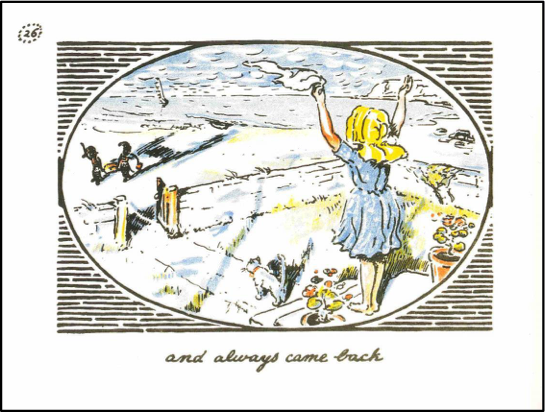

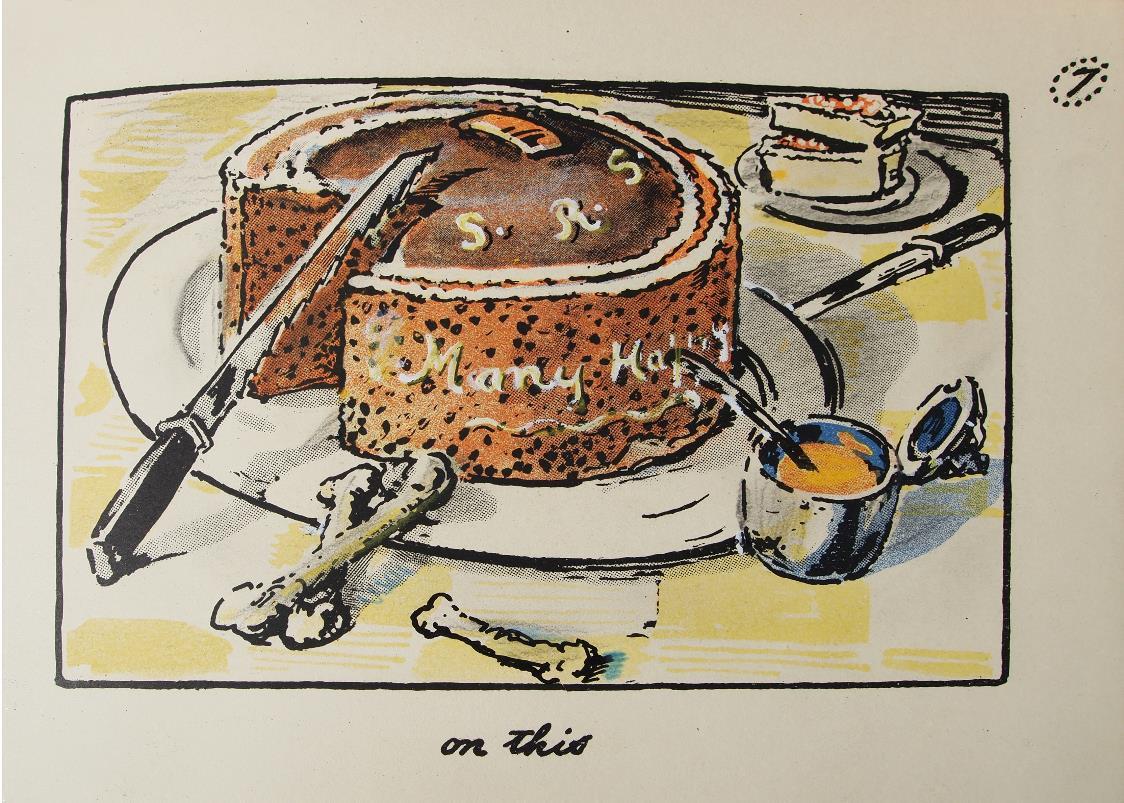

The Pirate Twins (1929) begins with the young child, Mary, finding an open scallop shell in the surf, which, by the third picture (when we are able to look inside and it has grown much bigger in relation to Mary) is shown to contain the Pirate Twins, two small black figures (they don’t come up to Mary’s waist) in antique pirate costumes: horizontal striped shirts, gold earrings, large buckled belts, and stocking caps. Mary, with a bunchy maternal bottom apparently caused by stuffing her dress into her underclothes to wade, takes them firmly by the hands and leads them home, where she starts bringing them up properly. She engages in bathing, feeding, teaching various lessons, and otherwise ‘playing house’ with these unexpectedly encountered seafarers. Their intractableness to domestic management is subtly evoked in the pictures first, then in the narrative, until the moment when they steal a boat and sail away, but always come back for Mary’s birthday: a particularly festive picture with sun shining in the window, curtains blowing, gulls sailing by, and a fine cake.

There are mysteries in the text. The first is, who is raising Mary? She appears to be living a separate life in the house, which is apparently occupied by others who have a piratical taste for crustaceans, rich cake, and rum. The ‘others’ are never seen or referred to. The second is a question of what the Pirate Twins might be. They most resemble the cloth dolls that Nancy made in their minimalist faces, flexible arms, rounded feet, and adult proportions. But Nicholson enhances the possibilities already there. He gives them clever hands and an un-doll-like expressiveness. Moreover, their physical nature appears as waterproof and resilient and hungry as that of humans, though their size changes drastically to fit their different tasks. Their appearance, rising from the surf like Venus, is funny (although it is not part of the story, properly speaking, a kind of alternative creation myth on the endpaper), but the ‘magical’ aspect of the Twins is reinforced by Nicholson’s framing of the pages. Schwartz’s reference to Jacques Callot’s inspiration in Nicholson’s work, the ‘transformations that come from seeing the world through a telescope’ and the ‘delights and deceptions’ of looking, applies here (pp. 47-48). The size of the globe and alphabet book, for example, is unknown, so the Twins’ smaller stature next to these items cannot be judged. A more perplexing problem exists in the outdoor scenes of the Twins marching in the surf or looking at the Milky Way through telescopes. It is hard to see where or how the reader would need to be standing in order to see the Twins in this way, unless a lens of some kind is being used. And the boat! Is it a toy boat next to another toy boat on the beach? Or have the Twins become large enough to manage an ordinary craft?

A conundrum about size and a foreshadowing of the escape. Faber and Faber 1929 edition, with WN’s preliminary sketch of a third Pirate. William Nicholson’s writings and drawings ©Desmond Banks.

The ‘new way of reading’ that was a feature of the Clever Bill advertisements means that in order to experience the tension between Mary’s desire for motherly play and the Twins’ desire to go back to pirating, each image must be ‘read’ in order to see the signs of the impending rebellion: the little boat in the bath, the scimitars acquired from the dress-up trunk, the crossed bones and knife on the cake plate, the snarling lobster, the sailor life in the alphabet book, the fact that the Twins have found the Caribbean on the globe. The pictures anticipate and amplify. They are the source of jokes, as well. To readers who know that Nicholson’s still lifes, as Merlin Jones remarked, sometimes have to do with knives cutting and opening up,

Arguably a turning point in the story, bagpipes may also allude to the Isle of Skye origin story. Andrew Jones Art, 2005. William Nicholson’s writings and drawings ©Desmond Banks.

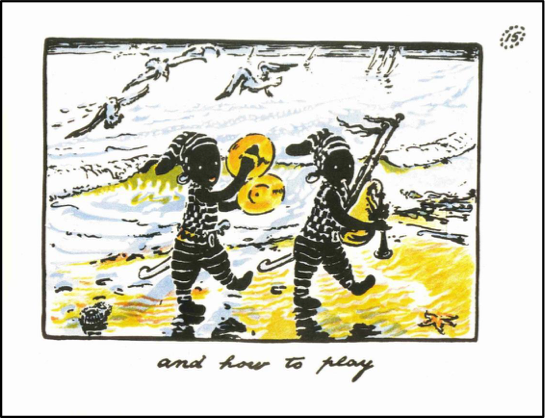

In terms of the Nicholson canon, a surprise occurs on the ‘play’ page before the overt rebellion: the eyes of the Pirates suddenly meet the gaze of the reader. They appear to have discovered that someone is looking at them. WN often did not paint a direct gaze; he favoured profiles when photographed and most often when he painted portraits (Schwartz, p. 84). And this is also the technique in Clever Bill for Mary and her toy soldier. But the Pirates, while playing in the surf, are revealing themselves while making a discovery that changes the rest of the text. Their silent, but self-reflexive, moment apparently provides them with critical mass to do something about their situation.

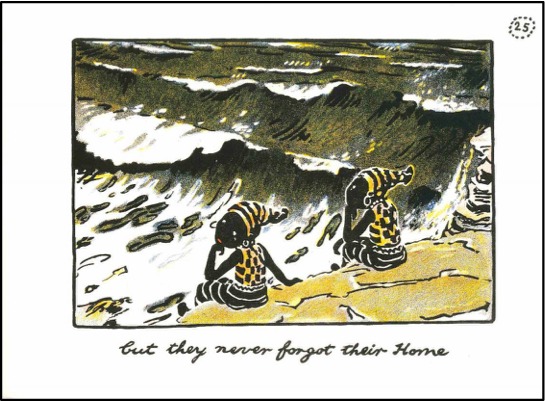

The picture following the rebellious escapade (when the runaway Twins sit on a rocky cliff over turbulent grey waves with tears rolling down their faces) is also an important turning-point. ‘But they never forgot their home’ it says, and the left-hand twin looks over his shoulder directly at the reader, again. The Twins’ self-revelation can appear to be Nicholson’s, as well. From his daughter Eliza’s point of view, the Pirates are her father because they were rebels as her father was, in some ways. He had, after all, run away to Paris to be an art student rather than accepting solid, middle-class prosperity; and he was devoted to his mother. She also mentions his tendency to hurry back to the women in his life (wives or mistresses) with bouquets.

Andrew Jones Art, 2005. William Nicholson’s writings and drawings ©Desmond Banks.

Although the authorial connection with the Twins is meaningful to those who admire his work, it does not really untangle the perplexities of gender and race variously raised in connection with the story. Picturebooks that depend upon pictures to convey narrative are always open to a variety of truths from a variety of readers. Modernist texts such as this one compound the difficulty. The issues can be looked at as a series of balancing acts, the kind that make the grotesque the grotesque: It is tedious that Mary (whose image in the book is greatly outweighed by that of the Twins) has the thankless role of trying to colonize the Twins. But she is young, and ‘house’ is an age-appropriate game. Additionally, she is imaginative (unlike Wendy) and the Twins enjoy her tutorial activities – she is their ‘home’. And Mary and the Cat are resilient; they are glad to see the Twins again, but there is no indication that they have been lost without them. They all seem to understand each other well.

There is no doubt that within the text (or within the autobiographical connections) the Pirate Twins are considered rebels against Mary’s attempt to guide their activities, and that their colour as well as their mysterious seafaring origin may be considered a reason for this, where Mary is white and the Twins are black in a racist society. Enjoying the possibilities and the identity of being a Pirate Twin may be a position of strength for Nicholson as a man and artist. But it can be associated with stereotype for others, nonetheless. Playing dominoes in bed (the Twins’ final rebellious act) is funny rather than horrific unless a reader feels that this activity reflects on the teachableness or rectitude of black children or, more likely, the author’s ability to take such children seriously.

The addition of the Cat completes the harmonious reunion. The Pirate Twins had previously ‘put things into’ the cat’s milk: polliwogs and hot sauce, apparently. Andrew Jones Art, 2005. William Nicholson’s writings and drawings ©Desmond Banks.

Their survival strategies are engaging and efficient. They are not faithless; they are simply determined to live their lives in their own way. The happy ending ‘always came back | in time for | Mary’s birthday’ is a bargain. The Twins love and miss Mary, but they come home on their own terms.

The Pirate Twins are a matter for personal judgment, but they were intended as role models, unlike the Barrie pirates who exist only to be vanquished. WN’s pirates prevail. If they are a self-revelatory statement about himself, being true to oneself was a lesson he was willing to pass on. He left an incomplete version of ‘The Pirate Trips’ containing the initials of his son Ben Nicholson’s and Barbara Hepworth’s triplets (Sarah, Simon, and Rachel, born 1933) in icing on the rich cake. It is a copy of The Pirate Twins with an additional ‘twin’ added in the illustrations.

Faber and Faber, 1929, with WN’s addition of his grandchildren’s initials, birthday greeting on the side of the cake, and extra bone on the table. William Nicholson’s writings and drawings ©Desmond Banks.

In reviewing the history of ‘fantasy in everyday life’ (or magical realism) in children’s literature, critics often look to the work of E. Nesbit (1858-1924), in which parents are tidily sent off to warm climates for their health or otherwise out of the way so that children may encounter magic without awkward questions. The Pirate Twins and Clever Bill belong to this tradition. They are also artifacts of an era in which British children were frequently in the hands of caregivers who were not their parents, a recurring topic in the annals of the Graves/Nicholson children. From the beginning of Nicholson’s publishing career – his An Alphabet, his London Types, his wartime picture ‘A Belgian of Tomorrow’, those Peter Pan pirates – he had demonstrated a belief that children are tough and capable.

But Mary’s lone state (not surrounded by other family children or helpers, next to the sea that gives and takes away, surrounded by mystery), hints at the inner resources and spunk that such a child must have. Written at a time when the golden Sutton Veny days were in the past, hellos and good-byes are not casually conceived. Mythic echoes of the Selkie Girl, who returns to the sea, creep in. The grotesque, which makes it hard for the story’s admirers and repudiators to clarify their discussion, also balances the hilarious and the sad.

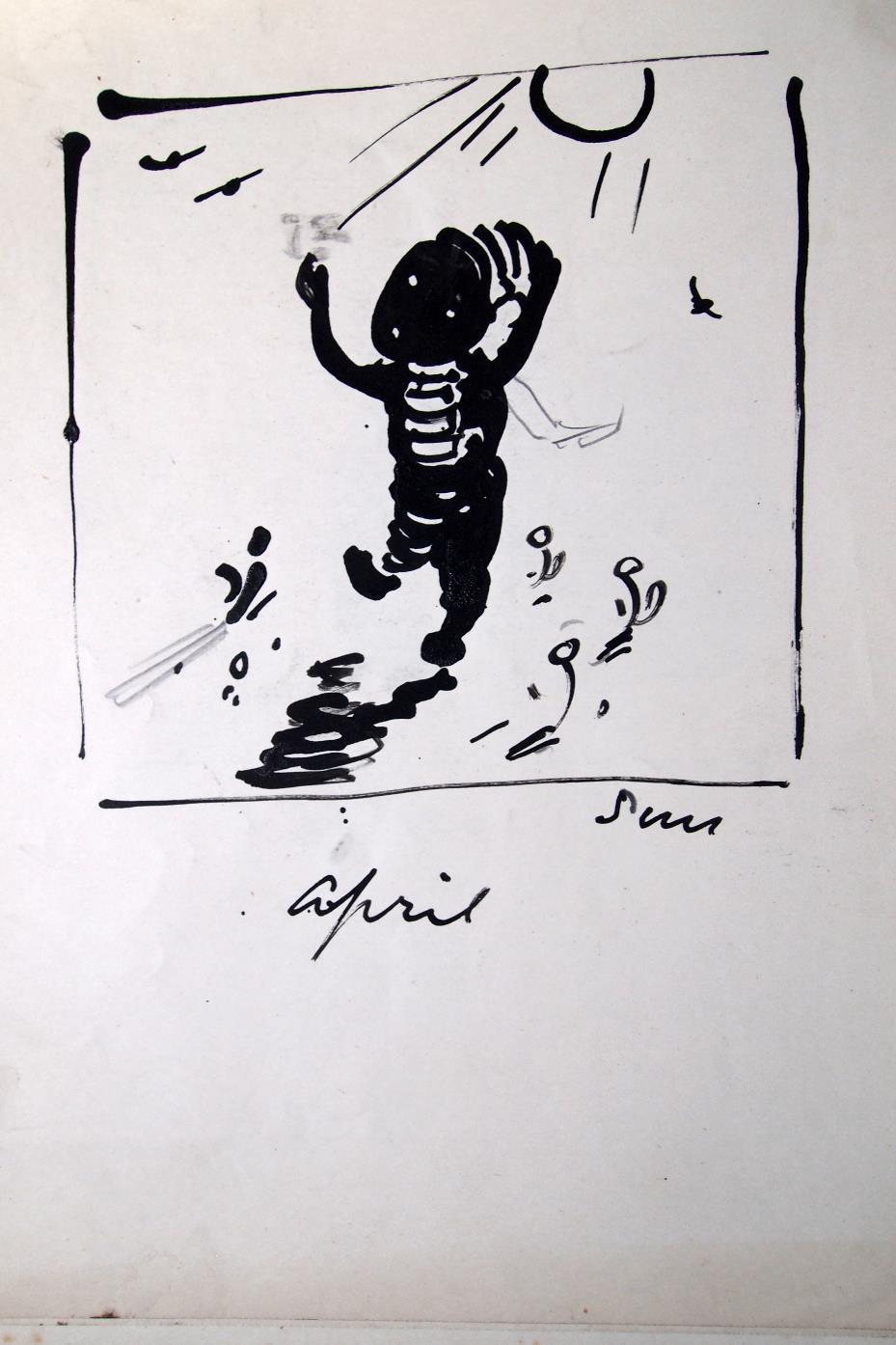

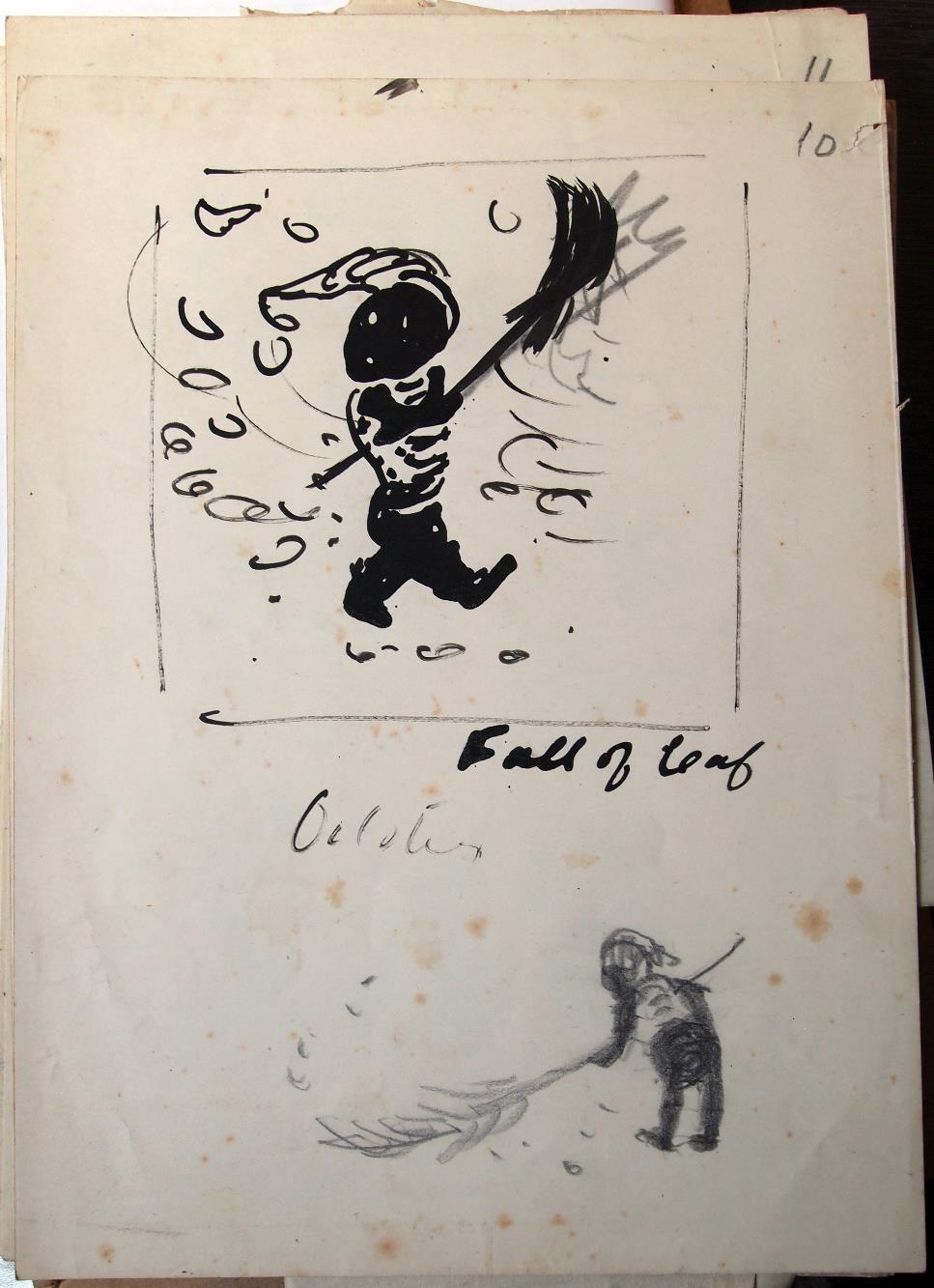

One of nine sketches of the Pirate Twins intended for a calendar. William Nicholson’s writings and drawings ©Desmond Banks.

Another sketch of the Pirate Twins. William Nicholson’s writings and drawings ©Desmond Banks.

Marilynn Strasser Olson, distinguished professor emerita, English Department, Texas State University, was an associate editor and editor of the Children’s Literature Association Quarterly from 1991-2000. Children’s Culture and the Avant-Garde (2012) and subsequent essays concern the connection of children’s literature and art; Olson has contributed to articles on astronomy, art, and literature with her husband, Donald W. Olson. She is currently co-editing a study of favourite presidential childhood reading.

NOTES

to Andrew Jones September 2004. Used by permission of Maurice Sendak; Sendak mentions The Pirate Twins as an influence on Where the Wild Things Are: Maurice Sendak, Caldecott & Co. (New York: Farrar Straus Giroux, 1988), p. 166.