|

Search Help |

|

Links Robert Graves Website Other RG Resources |

Obituaries

Beryl Graves (1915-2003), the wife of Robert Graves, who inspired and edited his love poetry

The wife of Robert Graves, who inspired and edited his love poetry

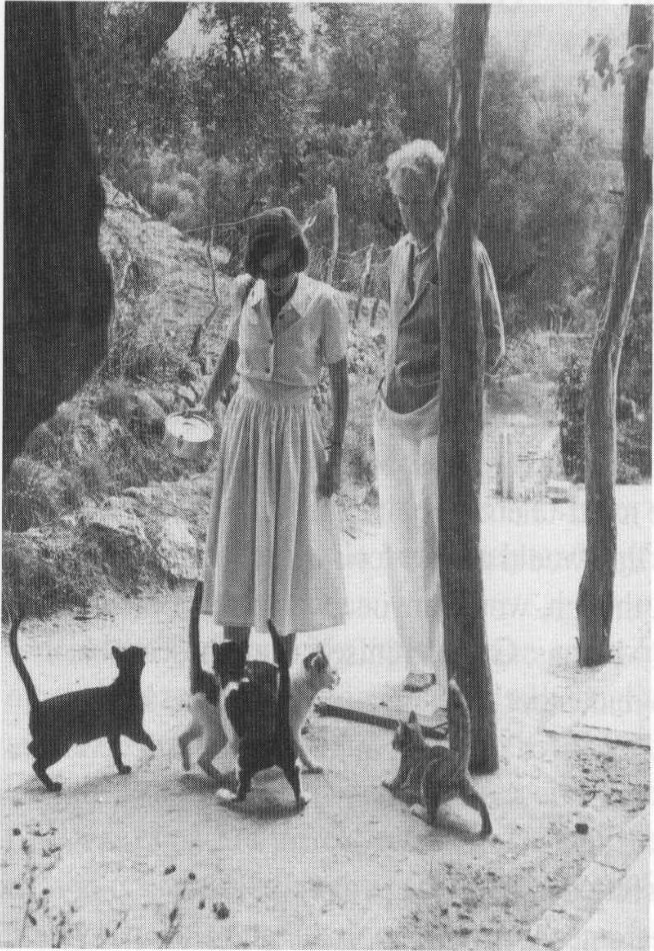

Beryl in Deyå with Robert and some of her cats, 1954 Photo by Daniel Farson/OHulton

Beryl in Deyå with Robert and some of her cats, 1954 Photo by Daniel Farson/OHulton

Archive/Getty Images

This obituary was first published in the Guardian on I November 2003 and is reproduced here, with only minor changes, by kind permission of Guardian Newspapers Ltd.

Beryl Graves, who died aged 88 on 27 October 2003, inspired some of the finest English love poems of the twentieth century. Fifty years after most of them were written by her husband Robert, she produced (with Dunstan Ward) a scholarly edition of them that will stand as the authoritative text.

Beryl was born in Hampstead, London, the daughter of Sir Harry Pritchard,

President of the Law Society, and educated at Queen's College, Harley St. In 1932, she won a place at Oxford to study politics, philosophy and economics, one of the first generation of women to be granted full membership of the university and to be awarded full degrees.

While at Oxford she developed a strong political intelligence and joined the university Labour club. On her 21st birthday she toasted the electoral victory of the revolutionary Popular Front in Spain, unaware that this would unleash a series of events that would lead her, a year later, to meet the poet and writer Robert Graves, who had also celebrated the Republican left's historical victory, but who was forced to abandon his home in Mallorca when the violence of the ensuing Civil War threatened to engulf him.

When she met him, Graves, 20 years her elder, had achieved international recognition through Goodbye To All That (1929) and the two Claudius novels (1934). He had moved to Mallorca in 1929, following the separation from his wife Nancy Nicholson and their four children, and the attempted suicide of his companion and literary partner, the American poet Laura Riding. He and Riding settled in the idyllic mountain village of Deyå, on the north-west coast of the island, where they created a small artistic community. By the time they left in 1936, Graves had recreated himself as a poet under Riding's stern influence, but their relationship had soured.

Beryl and Laura were alike in that each had a sharp intellect and formidable strength of character, but where Laura could be delusional and judgmental, Beryl was the embodiment of sanity and tolerance. She was also young, strikingly beautiful and had a playful sense of humour.

When Riding expelled Graves from her circle in 1938, he and Beryl were already in love. Graves's loves were never without complications, however. This time it was the fact that Beryl was already married to his friend Alan Hodge. Beryl and Alan settled matters quickly and without fuss and he and Graves went on to write two books together.

In the 1930s and 1940s Graves wrote the extraordinary group of love poems to Beryl which have established his poetic reputation. These poems celebrate a sense of liberation and hope, at having been rescued from personal destruction by love, as well as his deep admiration for Beryl's strength and self-containment:

In your sleepy eyes I read the journey

Of which disjointedly you tell; which stirs

My loving admiration, that you should travel Through nightmare to a lost and moated land, Who are timorous by nature.

There is also a playfulness, as in 'Despite and Still':

Have you not read

The words in my head, And I made part

Of your own heart?

We have been such as draw

The losing straw -

You of your gentleness,

I of my rashness,

10 GRAVESIANA THE JOURNAL OF THE ROBERT GRAVES SOCIETY

Both of despair — Yet still might share This happy will:

To love despite and still.

After the war, Graves returned to Deyå, this time with Beryl and their three young children, William, Lucia and Juan. Their fourth child, Tomås, was born in Spain. Graves found Canellufi, the house he had left at a few hours' notice in 1936, to be untouched by the war. Beryl created an atmosphere of friendship, fun and creativity around Canellufi that had been missing in the ideologically driven and self-consciously artistic community established by Laura.

Whereas Laura had tried to create a community firmly in her own image, with herself as its centre, Beryl was unassuming, with a tendency to put others, and especially Robert, before herself. As Graves became increasingly famous, she welcomed endless visitors from around the world and presided with grace and wit over numerous dinners, picnics, parties and impromptu plays and readings. The important things of life became embedded in the daily rituals of playing with children, gardening, harvesting the olives, cooking for friends. She had a passion for keeping animals, from the pair of alligators she had raised as a child, to the Abyssinian cats she flew over from Harrods. She travelled widely, read voraciously in English, Spanish and Russian, and studied the night sky.

Graves's poetry, however, was fuelled by an emotional turmoil which a settled home did not provide. As he became older, he became more, rather than less, obsessed with achieving a body of poetry that he described as a pursuit of 'personal truth', and a resistance to the erosion of value in a society driven by money, power and technology. Such poetry came only when 'the emotions of love, fear, anger, or grief are profoundly engaged' and he orchestrated this by developing romantic attachments to a series of four young women who became known as his muses.

After the First World War he had resisted psychiatric treatment for his shell shock, because he feared that a cure would make him a less interesting writer. It was, he said, 'less important to be well than to be a good poet'. In a similar way, it now seemed less important to be happy, than to pursue his poetic vocation to what seemed its inevitable conclusion.

For the most part, the muse relationships were idealistic and platonic. Even so, Beryl's position was understandably difficult. She responded with characteristic strength of character. She shared Graves's vision of the importance and value of his work as a poet and maintained an unwavering belief in him and their pledge to love each other 'despite and still'.

The result was that their love endured, and all but one of the muses joined her own circle of close friends. In his last years Beryl nursed Robert through a form of Alzheimer's with compassion and devotion.

O Guardian Newspapers Limited, 2003.

Beryl Graves, Editor, and Honorary President of the Robert Graves Society, born 22 February 1915, died 27 October 2003.

Paul O’Prey is Vice-Chancellor of Roehampton University.