Biographical Studies

‘The Most Terrible of His War Poems’: Robert Graves, Siegfried Sassoon, and the Hidden Anxieties of Post-War Homoerotic Revelation

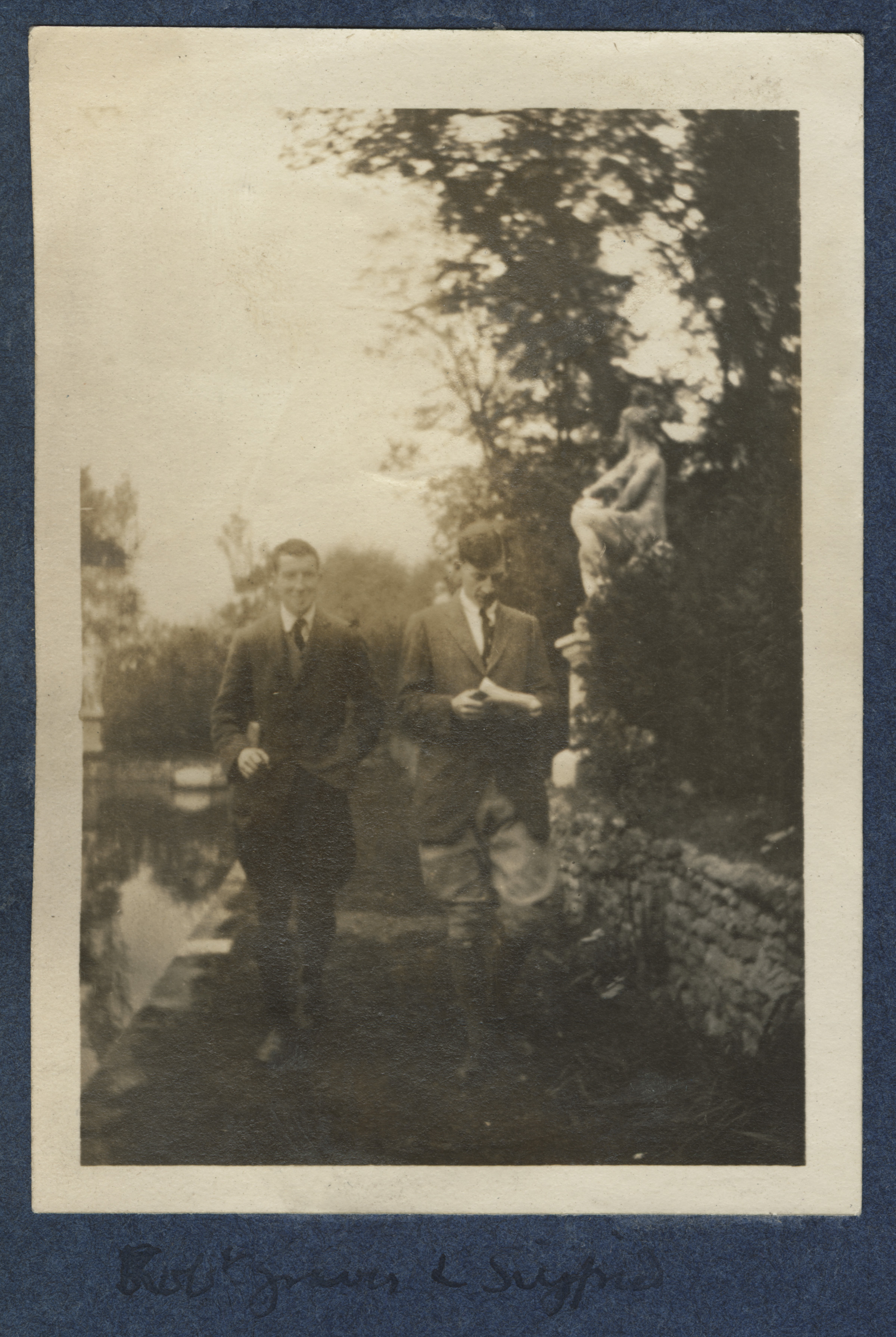

Robert Graves and Siegfried Sassoon, c.1920

by Lady Ottoline Morrell, snapshot print

Abstract: The article explores Siegfried Sassoon’s semi-covert expression of his intensified anxiety about Graves’s public discussion of his life with particular attention to a darkly jocular epistolary poem that Sassoon had sent from the American Red Cross Hospital to Graves, adding new detail to the relationship between Graves and Sassoon, one of the most fascinating in twentieth-century letters.

Keywords: homoeroticism, epistolary poetry, friendship, Oscar Wilde

___

One of the most vexed literary relationships in the history of the First World War in Britain is that between Robert Graves and Siegfried Sassoon, an intense, emotionally protracted friendship that began in wartime, when Graves and Sassoon were fellow soldiers with literary aspirations, but which did not survive the 1929 publication of Graves’s memoir Good-Bye to All That (GBtAT). Graves’s publisher Jonathan Cape had sent Sassoon an advance copy of the book, doubtless hoping for a favorable endorsement but which prompted Sassoon – just six days before the volume’s publication – to demand the removal of several pages related to Sassoon, among them a final reference to Sassoon’s mother grieving though spiritual communication for her dead son Hamo, who had died in battle, and an epistolary poem that Sassoon had written to Graves on 24 July 1918. Although Graves had reprinted the poem in truncated form, Sassoon was alarmed by the possible public display of his addled state. Sassoon’s objections forced Cape, probably out of fear of legal action, to redact what was printed on those pages and to blot out the sentences with asterisks in those editions that had not yet been printed. After a bitter exchange of letters in 1930, the two men did not speak for some three years.

In a long 7 February 1930 letter Sassoon expressed what he called his ‘exasperation’ with Graves as he catalogued all of the errors he found in GBtAT, a book, Sassoon wrote, which had arrived like ‘a Zeppelin-bomb’, although he was partly forgiving about the retracted poem: ‘Your printing of my verse letter without my permission was excusable’, wrote Sassoon. ‘You could not have known that I should be shamed by its emotional exhibitionism (though you may have remembered that I tried to get it back from you some years ago, and you evaded me by sending a copy of it).

This elicited a 20 February 1930 response from Graves in which Graves summarized, with cool directness, what he saw as the causes for their falling out – namely, Sassoon’s feelings about Graves’s wife Nancy and paramour Laura Riding as well as Sassoon’s supposed sexual feelings for Graves:

The friendship that was between us was always disturbed by several cross-currents; your homosexual leanings and I believe your jealousy of Nancy in some way or other; later Nancy being in love with you (which no doubt you noticed and were afraid of) for several years (until 1923 or so) then your literary friendships which I could not share; finally your difficulty with the idea of Laura. But it never seemed impossible to me until you broke down over the Gosse business. I can’t remember about Hardy; I remember forwarding a request to you from a publisher about his life. When a man dies, I regard him as dead and never go into mourning: a necessary hardness that I have cultivated in the last five years. Your delicate and restrained writing: be yourself, Siegfried.

This represents a raw tangle of personal and literary judgement and speculation, evoking not one but two sets of imagined love triangles as well as self-revelation about Graves’s ‘necessary hardness’. The accusation of falseness, restraint, and preciosity on Sassoon’s part is a running theme throughout Graves’s understanding of Sassoon. Although he initially claimed to admire Sassoon’s collection of verse The Heart’s Journey (1923), he later dismissed it as ‘lace-Valentine vulgarity’ and a ‘monument to [Sassoon’s] emotional shortcoming’.

Graves’s letter generated a defensive response from Sassoon, who forthrightly addressed the accusations of jealousy and homosexual attraction:

I was never jealous of Nancy. But I would have liked to have seen you independently sometimes. In her presence I was nervous and uneasy. She didn’t give one much assistance, did she? For you I felt affection; but physical attraction never existed.

Graves responded with a resentful remonstrance about the withholding of money: ‘Signing fat checks for your friends; the indelicate irony of it is that had you thought of signing one when you heard of ‘my troubles’ – which left us all without money – I would not have been forced to write Goodbye to contribute to the work of restoration’.

To a considerable degree both writers resisted the advances of literary modernism – specifically, the achievement of T. S. Eliot, about whom Sassoon expressed querulousness. Yet much of the tension between Graves and Sassoon stemmed from their competing accounts of the war and their different investments in war writing. The array of autobiographical narratives of his war experience that Sassoon produced – the Sherston trilogy, an autobiographical trilogy beginning with The Old Century, three-volume Diaries, the often-autobiographical poetry, not to be mention the voluminous body of letters, most of them still unpublished – create a self-consciously shifting narrative. While Graves said most of what he thought about the war in GBtAT, Sassoon was a lifelong purveyor of innumerable wartime personae, no single one of them necessarily on speaking terms with any other. In the 2 March 1930 letter to Graves defending himself against Graves’s insinuation that he had been disingenuous in his Sherston memoirs, Sassoon admitted that he had split himself into five-fold personae. ‘No one is more aware than I am that Fox-Hunting Man is mere make-believe’, he wrote. ‘But it isn’t (as your review implied) a piece of facile autobiographical writing. Sherston is only 1/5 of myself, but his narrative is carefully thought out and constructed.

Far more than is the case with any other British World War I writer including Graves, Sassoon has been construed by critics and historians as a paradigmatic case of wider cultural concerns. For Paul Fussell, Sassoon’s relation with young men at the Front, as well as with his psychiatrist W. H. R. Rivers, provided the male ‘dream friends’ who had been the imaginary companion of Sassoon’s boyhood fantasies. Through her exploration of Sassoon’s relation with Rivers, Elaine Showalter suggests that the coded Sherston memoirs comprise a ‘disguised epic of homoerotic feeling’.

More recently, there has been a wealth of new information, along with a seemingly tolerant understanding of homosexual issues, provided by the biographers Paul Moeyes, Jean Moorcroft Wilson, Max Egremont, and John Stuart Roberts.

Welcome as this attention is for literary scholars of the First World War, a didactic biographical momentum often shapes these newly frank accounts. That the survivor of the Somme and skirmishes around Morlancourt, the veteran of Craiglockhart mental hospital, one of the war’s key dissenting voices, had been brought down by the dandiacal Tennant and that he then retreated into a sterile married life, morosely conflicted about his sexuality, has come to serve as the dominant myth of Siegfried Sassoon. The protest poet whose 15 June 1915 ‘A Solder’s Declaration’ was a rare instance of outrage against a war that would end in some ten million deaths became, the unstated biographical logic goes, the helpless casualty of a misguided romantic infatuation. ‘The final indignity for Sassoon’, writes the critic Elizabeth Lowry in a 1999 review of Roberts’s biography in the Times Literary Supplement, ‘was a desperate fling with Stephen Tennant, a tubercular piece of country-house totty’.

My examination of the Graves-Sassoon friendship is drawn substantially from three archival sources: Sassoon’s copy of GBtAT located in the Beinecke since 2015; the annotated copy Sassoon and Edmund Blunden created on the evening of 7 November 1929 located in the Berg Collection at the New York Public Library; and the letters of Sassoon’s friend, the eminent writer Edmund Gosse, located in the Rutgers University Library, a correspondence that was drawn on for a 1931 volume edited by Evan Charteris so that references to an anti-homosexual wartime campaign in Britain, generated by the Maud Allen ‘Salome’ case, were deleted, possibly at Sassoon’s instruction. Sassoon’s affiliation with Gosse was long-standing and professionally advantageous; his mother had been friends with Gosse’s wife Nellie and his Uncle Hamo had been the best man at Gosse’s wedding. Moreover, although Gosse regarded some of Sassoon’s war-related poetry to be too bruisingly sardonic and his 1917 public rebellion against the war a troubling lapse in judgment, the older man had served as valuable mentor as Sassoon embarked on his literary career. (In an examination of the Gosse-Sassoon correspondence Paul Fussell has suggested that the sometimes-fitful relation between the two men resembles the troubled relationship at the heart of Gosse’s memoir Father and Son (1907).

The friendship between Graves and Sassoon has continued to draw biographical and critical attention, some of it based on new archival sources. In a 3 February 2016 Times Literary Supplement essay on Sassoon’s copy of Graves’s memoir in the Beinecke, Jean Moorcroft Wilson characterized the much-annotated volume as a ‘work of art’ that further discloses Sassoon’s animus against Graves. Wilson does not note, however, that there is a specificity to that animus, one related to Sassoon’s fears of homosexual revelation that GBtAT evidently had stirred up in the poet. As we shall see, among several details of the annotated Beinecke volume is a coy reference by Sassoon to what is probably a homosexual blackmail case, an undated newspaper account of which Sassoon had inserted into his copy of Graves’s memoir.

I want to explore Sassoon’s anxieties about Graves’s public discussion of their relationship. The Beinecke, Berg, and Rutgers archival evidence suggests that in the post-World War I period, as both Graves and Sassoon emerged as major public figures, Sassoon became increasingly cautious about his visible-but-invisible reputation as a lover of men and that he worried about references to his sexuality in Graves’s writing – quite understandably given that homosexual relations were illegal in Britain until 1967 (as it happens, the year of Sassoon’s death). Sassoon’s awareness of his sexuality dates back at least to 1906. In a 27 July 1911 letter to the pioneering socialist and homosexual activist Edward Carpenter, he wrote:

Until I read The Intermediate Sex, I knew absolutely nothing about of that subject (and was entirely unspotted, as I am now), but life was an empty thing, and what idea I had about homosexuality was absolutely prejudiced, and I was in such a groove that I couldn’t allow myself to be what I wished to be, and the intense attraction I felt for my own sex was almost a subconscious thing and my antipathy for women a mystery to me. It was only by chance that I found my brother (a year younger) was exactly the same. I cannot say what it has done for me. I am a different being and have a definite aim in life and something to lean on, though of course the misunderstanding and injustice is a bitter agony sometimes. But having found out all about it, I am old enough to realize the better and nobler way, and to avoid the mire which might have snared me had I know 5 years ago. I write to you as the leader and a prophet’.

Leaving aside his conflation of male same-sex desire and ‘antipathy’ towards women, Sassoon’s clear-eyed self-understanding here is remarkable. His optimism about the future he saw as heralded by his ‘leader and prophet’ would not, however, outlast the war, when the forces of a social purity campaign and existing legal strictures made daily life inhospitable to many homosexual men.

The apprehensions disclosed in the Beinecke volume echo those that were evident in the circumstances surrounding Sassoon’s threatening 1929 letter to Graves’s publisher. What partly had alarmed Sassoon in 1929 was that Graves had discussed a visit to the Sassoon home at Weirleigh and had witnessed Sassoon’s mother trying to communicate with her dead son, Hamo, who had been killed in the war, in what Graves described as an alarming middle-of-the-night séance. In GBtAT he recalled telling Sassoon. ‘I am leaving this place’, after an evening of rattling noises and screams in the night. ‘It’s worse than France’. On this incident Sassoon’s comment in the annotated Blunden-Sassoon volume is wickedly personal. Where GBtAT Graves describes Sassoon’s mother’s demeanor with the observation that ‘She was religious and went about with a vague bright look on her face’, Sassoon underlines the sentence and writes

I remember RG’s visit to Weirleigh only for the fact that he stayed a week and never took a bath. Would he like it if I put that in a book? The incidents described are almost entirely apocryphal. To me this passage is unforgiveable.

Sassoon does not explain what part of Graves’s account is ‘apocryphal’ although Graves did make small alterations of fact perhaps as a way of protecting certain individuals (for example, by referring to Sassoon’s younger brother Hamo without his name and as Sassoon’s ‘eldest brother’).

Nonetheless, what must have been even more alarming to Sassoon was that Graves – without Sassoon’s permission – had included in his autobiography a 24 July 1918 free-form, bitterly jocular epistolary poem that Sassoon had sent from the American Red Cross Hospital to Graves on that same day. (Sassoon had been accidentally injured by a bullet from a British soldier who had mistaken him for a German, a near-deadly incident of ‘friendly fire’.) Sassoon’s verse-letter seems to have been part of epistolary badinage on the part of the two poets. Sassoon’s ‘A Letter Home’, written from Flixécourt, France in May 1916, was an affectionate poem written to Graves later included in Sassoon’s first collection of verse, The Old Huntsmen.

Robert, when I drowse tonight,

Skirting lawns of sleep to chase

Shifting dreams in mazy light,

Somewhere then I’ll see your face

Turning back to bid me follow.

With similar tender regard, Graves wrote a 1917 verse poem to his friend imagining St. Peter, Graves and Sassoon on a happy journey:

And one day we three

Shall sail together on the sea

For adventure and quest and fight

And God! What Poetry we’ll write!

A decade later, however, such affectionate regard on the part of both men would shade into acrimony over a range of subjects, from Sassoon’s annoyance at Graves’s attitude towards Thomas Hardy and Edmund Gosse (both of whom Graves considered too doggedly Victorian in their literary sensibilities) to Graves’s negative review of Memoirs of a Fox-Hunting Man, which Graves claimed had ‘side-stepped the moral question’. At times the disagreement centred on Sassoon’s idealized sense of his wartime comrades versus Graves’s mordant appraisal of his fellow combatants. This became most apparent in an exchange in which Sassoon, in a postscript to a 7 February 1930 letter, objected to Graves reference in GBtAT to British officers in Amiens having visited brothels while their battalion was briefly housed in Montagne, to which Graves responded with a crude personal jab at Sassoon’s supposed lack of erotic experience: ‘It doesn’t take long to fuck; but perhaps you don’t know about that’.

The Berg Collection’s copy of GBtAT reveals Blunden and Sassoon’s shared, caustic enmity towards Graves. For example, Blunden mocks Graves’s ‘callous egotism’ and his role as ‘merely the showman, out to create a sensation’. Graves became aware of Blunden and Sassoon’s mischievous undertaking, calling the annotated volume ‘a bomb under my monument’.

Despite his morally and probably legally indefensible decision to try to publish ‘Dear Roberto’ without gaining consent from Sassoon, Graves was correct in his characterization of the poem. This is the most terrible of Siegfried’s war writings because the poem distils so many of the apprehensions and fantasies preoccupying Sassoon as the war came to an end. As Patrick Campbell has noted of the verse letter, ‘In the poems of Counter-Attack, Sassoon had characteristically played down his feelings by the frequent use of irony or by allowing the victims of war to speak for themselves. Here there is no such distancing’.

The poem begins in both the first- and third-person, as he describes the ‘quivering songster failed to die | Because the bloody bullet missed its mark’. But the poet/patient is troubled, afflicted with what is a gnarled neologism, ‘Sleeplessexasperucide | O Jesu make it stop!’ The literary set that had hailed him is evoked is another neologism, a jumbled reference to the ‘first afternoon when MarshMoonStreetMiekeljohnArdoursandenduranSitwellitis prevailed’ – Rupert Brooke’s friend Eddie March, Oscar Wilde’s one-time lover and friend Robbie Ross (who resided on Moon Street in London), Roderick Meiklejohn – and the poet Robert Nichols, Osbert Sitwell, as well as a ‘Jolly Otterleen knocking at the door’ (the society hostess Ottoline Morrell, in the poem bearing ‘some golden daisies and some Raspberries’ in a box only to be turned away by a nurse), but none of them affectionately and, indeed, the concluding “itis” suggests they collectively constitute a disease. The references represent, too, a bored catalogue of do-gooders who cannot save the psychically wounded poet, a ‘quivering songster who failed to die’, and who, as the poem develops, suffers less from shellshock than self-disgust at the heroic public protest posture that Sassoon has come to assume, a role that, as well see, is imperilled by a secret sexual self.

One recurring theme of the poem is an anxiety and despair on the speaker’s part that in taking a public stance against the war effort and in entering a hospital he has abandoned his fellow soldiers:

My God, My God, I’m so excited; I’ve just had a letter

From Stable who’s commanding the Twenty-Fifth

Battalion

And my company, he tells me, doing better and better.

Pinched six Saxons after lunch,

And bagged machine-guns by the bunch.

This forced jocularity, in which the killing of Germans has the ease of a sports triumph and in which the name of the commander, Stable (Officer Stable Wintringham) provides a neat counterpoint to the clearly unstable Sassoon, gives way to the poet’s guilt and shame about his absence from the front:

But I – wasn’t there –

O blast it isn’t fair,

Because they’ll all be wondering why

Dotty Captain isn’t standing by

When they come marching home.

But I don’t care: I made them love me

Although they didn’t want to do it, and I’ve sent them

a glorious Gramophone and God sent you back to me

Over the green eviscerating sea –

This represents a remarkable contrast to one of Sassoon’s most famous war poems, ‘Banishment’, of the year before, written at Craiglockhart Hospital in 1917, in which it is the love of his fellow combatants that becomes a heart-wrenching inducement to Sassoon’s ‘mutiny’ and his decision to return to the front:

They trudged away from life's broad wealds of light.

Their wrongs were mine; and ever in my sight

They went arrayed in honour. But they died, –

Not one by one: and mutinous I cried

To those who sent them out into the night.

The darkness tells how vainly I have striven

To free them from the pit where they must dwell

In outcast gloom convulsed and jagged and riven

By grappling guns. Love drove me to rebel.

Love drives me back to grope with them through

hell;

And in their tortured eyes I stand forgiven.

Whereas the ‘love’ of the ‘Dear Roberto’ poem is forced upon Sassoon’s fellow soldiers, who reluctantly assent to it, here the ‘love’ that drives the poet to rebel and return to battle is unassailably pure, in a scenario in which Sassoon is

‘forgiven’ by his beleaguered co-combatants.

The ‘love’ between Sassoon and his fellow soldiers is thus complicated, questioned, and imperilled in the verse poem to Graves. The teasing obliquity of Graves’s comment – ‘I cannot quote it in full’ – only became clear when the poem was published in full in 1979. Some of Graves’s changes to the poem were clearly protective of his friend; where Sassoon had written of himself as ‘Dotty Captain’ Graves substituted ‘Captain Sassons,’ at once respectful of military rank and plainly affectionate in its referencing of one of Sassoon’s nicknames. Moreover, what Graves had left out of the poem in GBtAT would have had socially and even legally perilous implications for Sassoon. This is especially true of the penultimate lines of the poem:

O Rivers please take me. And make me

Go back to the war till it break me.

Some day my brain will go BANG,

And they’ll say what lovely faces were

The soldier lads he sang.

These excised lines represent a doubly meaningful self-revelation of homoerotic affiliation on Sassoon’s part – first in its reference to the poet’s Craiglockhart Hospital physician,

W. H. R. Rivers, the pioneering Freudian psychiatrist and anthropologist who helped introduce the ‘talking cure’ to the treatment of ailing military officers. Earlier in the poem Sassoon affectionately describes Rivers as ‘the “reasoning Rivers” who ran solemnly in, | With peace in the pools of his spectacled eyes and a wisely omnipotent grin’.

However, in the closing, emotionally heightened lines of the poem, the physician becomes a more vexed figure. ‘O Rivers please take me’ – the grateful patient, in a usually unstated psychoanalytic scenario, cries out for an amorous embrace from the understanding analyst, only for Sassoon to then immediately undercut that emotional plea with a complaint against the physician’s evident complicity in the war effort. ‘O Rivers please take me. And make me | Go back to the war till it break me’.

Complicating Sassoon’s relationship with Rivers is the question of the lifelong bachelor Rivers’s own sexuality, a matter of some biographical conjecture.

Graves, however, was in possession of the poem and some of Sassoon’s fears would soon be justified. For mysteriously, the poem as it originally appeared in Graves’s memoir was published later that year under the name ‘Saul Kain’, a pseudonym Sassoon had employed for his first collection of poetry, The Daffodil Murderer (1913). Published by The Unknown Press and entitled ‘A Suppressed Poem’, 500 copies were printed without Graves’s name and once again minus the lines referencing Rivers, the ‘lovely faces’ of lads, and Sassoon’s Jewish identity, introduced with the comment, ‘Siegfried had been shot through the head while making a daylight patrol through long grass in No Man’s Land. And he wrote me a verse letter’. Suspicion about this pirated edition fell on Graves, although the attribution has been denied.

Ultimately, however, Graves had the last word in the Sassoon-Graves feud when he publicly spoke of his former friend’s sexuality. Less than two years after Sassoon’s death in a 1969 interview in the Paris Review, Graves replied to a question as to why he did not write poetry about his war experience as Owen and Sassoon had done. He responded that he had destroyed his early ‘journalistic efforts’ (a telling terms since Sassoon had once criticized his friend’s ‘journalistic’ writing), adding that ‘Sassoon and Owen’ had written ‘journalistic’ verse and noted that both men ‘were homosexuals, though Sassoon tried to think he wasn’t. To them, seeing men killed was as horrible as if you or I had to see fields of corpses of women’.

At long last Graves was able to accomplish what he could not in 1929 – namely, to speak ‘in full’ of Sassoon’s erotic preferences. In Graves’s telling, Sassoon and Owen saw their wartime comrades (and perhaps enemy combatants) as potential lovers, a potentiality that was destroyed in the grim reality of combat, perhaps a reference to (the classicist in Graves would have been aware of the history) the Sacred Band of Thebes, a troop of soldiers consisting of 150 male lovers which formed the elite force of the Theban army in 4th century BC. While Graves’s acrid tone here makes it clear he was not evoking an exalted homoerotic ancestry, as literary history it did capture something important, anticipating what Fussell would boldly and influentially taxonomize in The Great War and Modern Memory (1975) as ‘ladlove’, in which military life represented a homoerotic idyll from a more restrictive social environment in England itself, what Fussell was careful to describe as not an ‘active, unsublimated kind of [homosexuality]’ but something more like the ‘“idealistic”, passionate but non-physical “crushes” which most of the officers had experienced at public school’.

In the Blunden-Sassoon copy of GBtAT, bonds of male-male affection are apparent, as when Sassoon becomes protective of his friend Wilfred Owen, who, like Sassoon, had been cautious about revealing his homosexuality and whose early biographers suppressed what they knew about their subject’s romantic and erotic relations.

Owen wasn’t shaky. He’d been shell-shocked, but had recovered. The ‘cowardice’ was only an indefinite idea which worried R. G. picked it up from Scott- Moncrieff. R’s paragraph about O. is one of the worst things in his book, but no doubt he doesn’t count as a poet.

Sassoon’s dismay regarding the alleged cowardice of the friend whom he first me at Craiglockhart Hospital in 1917, and whose poetry he had helped to shape in the three months they spent together there, indirectly speaks of larger concerns. One of the innovations in treating shell-shocked officers developed by Sassoon’s physician, W. H. R. Rivers, was to guide his patients towards a realization that their psychic distress was not the result of cowardice but, rather, a natural reaction to the mind-shattering conditions of combat. Rivers’s therapeutic method was to place an emphasis on understandable mental anguish, as opposed to shameful ethical failure, as the key to curing his patients, an insight that Rivers in part drew from his reading of Freud.

Eventually Sassoon’s poem to Graves appeared as ‘Dear Roberto’, six years before Graves’s death, in Jon Silkin’s 1979 anthology of First World War poetry published by Penguin. In this version all of the excised lines were restored. Thus, Sassoon’s verse poem acquired a semi-canonical status. It resurfaced in full in the 1995 edition of GBtAT, edited by Richard Percival Graves, a volume that also restored the references to Laura [Riding] Jackson that Graves had eliminated in the 1957 edition of his book. The poem appeared in full yet again in full in Sassoon’s War Poems published by Faber in 1983, although, curiously, the poem is not included in Sassoon’s Collected Poems issued by Faber in 2002, which is essentially the volume first published in 1947. In a sense, the epistolary poem makes explicit the veiled or only partly visible homoeroticism of Sassoon’s published poetry.

Sassoon’s sexuality was not the only aspect of his identity that was camouflaged or excised in Graves’s truncated version of the poem. The original poem included references to Sassoon’s Jewishness (‘Yes, you can touch my Banker when you need him. | Why keep a Jewish friend unless you bleed him?’), a reference to Graves having asked Sassoon, the descendant of Jewish traders from Persia, for a loan – that is, some of his ‘Persian gold’ – for what Richard Perceval Graves has characterized as a ‘dairy-farming scheme’.(RPG, Good-Bye, p. 364) More mysteriously, the line ‘the wonderful and wild and wobbly witted sarcastic soldier-poet with a plaster on his crown’ loses the word ‘sarcastic’ in Graves’ reprinting of the poem, as if sarcasm were not a trait worth ascribing to Sassoon, although arguably sarcasm is the dominant tone of the poem. The subsequent line – ‘Who pretends he doesn’t know it (he’s the Topic of the Town)’ – is also cut by Graves, perhaps out of concern that Sassoon’s mental ‘wobbliness’ might be construed as guileful malingering to avoid charges of treason. Perhaps out of fear of offending a powerful hostess, Sassoon’s reference to ‘Ottolean’ – Lady Ottoline Morrell, a perennial target of spoofing by her friends in later years – is altered in Graves truncated poem to ‘Thingumbob’.

Sassoon’s copy of GBtAT in the Beinecke is a revelatory scrapbook, at times frankly personal and at other times recondite: sometimes both. Among the disparate items, for example, is a newspaper clipping (the newspaper and date are unclear) with the headline. ‘The Hon. Evan Morgan. Blackmail Suggested in Case in which His Name is Figured’. The article reads:

A suggestion that there might be blackmail behind a case in which was mentioned the name of the Hon. Evan Morgan, son of Viscount Tredegar, was made by Mr. Dummett, the magistrate at the Marlborough-street today. William Torquil James Goodwin, aged 21, was sentenced to three months imprisonment on a charge of loitering in Mayfair, W, with intent to commit a felony. A companion, Colin Smith, aged 20, described as a valet, was remanded in custody. Goodwin’s defense was that he called at a house in Charles Street to deliver a letter to Mr. Morgan asking for a job. He had been introduced to Mr. Morgan about three months ago by a friend, Philip Ford, at a hotel. Mr. W. F. Hood asked leave to address the court on behalf of Mr. Morgan, but the magistrate suggested that he should reconsider the proposal; it was pretty obvious what these men were. Mr. Hood said Mr. Morgan knew Goodwin and he helped any boy who was down and out. Mr. Dummonett [sic] said he appreciated that he did not impute anything to Mr. Morgan. The men were thorough undesirable persons.

It is likely that Sassoon knew Morgan, who had been in the Royal Welch Fusiliers along with Sassoon and Graves, and who in later years had a career as a poet and writer on art before a series of financial and homosexual entanglements with ‘rent boys’ alienated him from respectable circles and his family.

The Maud Allan case presented an especially fraught challenge to such men. Although none of Sassoon’s biographers have noted the case, it had a powerful impact on Sassoon and his friends. The storm erupted when Noel Pemberton Billing, a member of parliament and maverick right-wing journalist, attacked the Canadian dancer Maud Allan in his newspaper The Vigilante for fomenting what he sensationally called ‘The Cult of the Clitoris’. Further, Billing maintained that there existed a Black Book containing the names of 47,000 leading British men whose sexual perversions rendered them liable to blackmail by the Germans. Among those named were former Prime Minister Herbert Asquith and his wife Margot, targeted by Pemberton for their pacifist positions during the war but also for their affiliations with London’s artistic coteries.

Wilde’s ‘Salome’ provided the ideal target for a public campaign against sexual dissidents. Almost from the very first performance of the play in Paris in 1896, observers had an understanding of this updated biblical myth as sexually perverse, not only a play about a femme fatale but various kinds of erotic obsession. One of the trial’s indirect casualties – Robbie Ross, Oscar Wilde’s former lover and lifelong confidante – counted himself one of Sassoon’s closest friends; Sassoon’s Counter-Attack had been dedicated to him. The ‘Dear Roberto’ poem not only mentions Ross but Half-Moon Street, the street on which Ross resided as had Wilde before him and Sassoon and Osbert Sitwell had in later years. Sassoon probably wrote the Counter-Attack dedication to Ross – written amid the events surrounding the Maud Allan case – out of concern for Ross’s mounting troubles. In a 25 June 1918 letter from Gosse to Sassoon there is the following passage – expunged either by Sassoon or Gosse’s editor Evan Charteris from the letter reprinted in the Life and Letters of Edmund Gosse. Gosse, who had attended the Allan trial at the Old Baily, discusses the case’s effect on Wilde’s friend, a passage over which Sassoon has written by hand ‘Omit para. 2’ (and, indeed, the paragraph is omitted in the Charteris volume without any indication that there has been a deletion):

I am very glad you have dedicated your book to Robert Ross, whose unselfish goodness deserves every tribute. I am sorry to say he has been very much disturbed in spirit by the fetid and bedlamite vapours of the Billing trial – our [illegible] of the Titus Oates spirit in the ignorant and idle spirit of the lower middle class. But R. R. is better now, I think. His year long persecution (to me absolutely inexplicable and unpardonable) has shattered his nerves. To need to be assured every ten minutes, by all his friends in turn, that nothing matters and that it doesn’t matter whether it does or not. You must be one of those who uphold his courage. Really, if he could see it, his position is no worse but rather better than it was, for he no longer alone but has 46,999 comrades in misfortune!

Gosse references here the seventeenth-century English priest Titus Oates, who fabricated the so-called ‘Popish plot’, an alleged conspiracy by Catholic Church authorities in England to kill King Charles II, while there is more than an element of snobbery in Gosse’s distaste for the supposedly shiftless, unenlightened ‘lower middle class’, presumed supporters of Billing’s campaign. Meanwhile, the wry allusion to Billing’s innuendo concerning 47,000 compromised British men is a bitter testament to the perils faced by men such as Ross and Sassoon in the wake of Billing’s social purity campaign.

If Sassoon was uneasy in 1918 with the contradictory loyalties of soldier and versifier, the role of openly homosexual writer clearly had become even more untenable – an impossibility given the necessarily public nature of his role as protest poet. In a sense, there was no difference between the poet’s status as ‘Mad Jack’ – the daring soldier who went from hunting foxes in the English countryside to hunting Germans in No Man’s Land – and the radical opponent of the war effort who, even after his protest letter, returned to the front out of what Sassoon declared was the ‘love’ of his fellow soldiers. But the Maud Allan trial served to expose that ‘love’ as a covert, treasonous act of sexual malfeasance, just as the ‘Dear Roberto’ poem revealed the poet to have harboured an illicit attraction to men.

‘The papers are full of this foul “Billing case”’, Sassoon wrote in his diary for 2 June 1918. ‘Makes one glad to be away from “normal conditions”’.

I gave him a cheery word and a grin, and he smiled at me, standing there in his grimy slacks and blue jersey. I wonder if he thought it a strange thing to do? I hadn’t spoken to him since I talked to him like a father when he was awaiting his court marshal. Something drew me to him when I saw him first. ‘Linthwaite, a nice name,’ I thought, when he told me he was a first Battalion man. Then I saw him, digging away at road-mending, and he’s got a rotten pair of boots, which were an excuse for conversation, and I’ve loved him ever since (it is just as well he’s not in my present Company). And when he got into trouble I longed to be kind to him. And I talked to him about ‘making a fresh start, and not doing anything silly again’, while he stood in front of me with his white face, and eyes full of tears. I suppose I’d have done the same to any man in the Company who had a good character. But there was a great deal of sex floating about in this particular effort. No doubt he dreams about ‘saving my life’. I wish I could save his.

This extraordinary passage, in which tender fatherly feelings on Sassoon’s part give way to erotic attraction and intense emotion in the other man, though not explicitly expressed by Sassoon. Such feelings are then quickly denied because in his impulse to save the other man Sassoon notes that ‘there was a great deal of sex floating about’, as if the impulse to help or ‘save’ Linthwaite would be tainted or negated by erotic desire. It is a characteristically Sassoonian moment in which the desire for another man is obliquely introduced as an intensely vivid experience, paused over and even savoured, only to be immediately contained as somehow unallowable.

The Maud Allan case had repercussions among Sassoon’s coterie. Wilfred Owen was readying himself for what proved to be his final return to the front. Stationed in Ripon, he met a drummer boy whom he had known before the war. Owen called it an ‘emotional experience, and when he was declared fit for service he wrote to a cousin on 4 June – as the Allan trial was coming to a close – ‘Drummer Boy of Dunsden wept when I said goodbye. (I had seen him 3 times!) This you must not tell anybody. Such things are not fit for this generation of vipers’.

The Billing case represented, notably, the failure of Bloomsbury liberalism when confronted with a campaign that drew on a ferocious wartime paranoia which (this represented an ‘advance’ on the Wilde case) linked same-sex degeneracy with international treason and government corruption. In a 4 June 1918 diary entry, Cynthia Asquith noted her shock at the resolution of the trial

Papa came in and announced that the Monster Billing had won his case, Damn him! It was such an awful triumph for the ‘unreasonable’, such a tonic to the microbe of suspicion which is spreading through the country, and such a stab in the back to people unprotected from such attacks owing to their best and not their worst points. The fantastic foulness of the insinuations that Neil Primrose and Evelyn de Rothschild were murdered from the rear makes one sick.

The case signalled the startling afterlife of the mephitic atmosphere of the Wilde trials of twenty years before, this time over a specific work by the playwright, the Biblical drama of a young princess who harbours a necrophiliac passion. As with Wilde’s several trials, the charges of homosexuality were pointed, although this time the supposed dangers of lesbianism, somewhat inexplicably linked to accusations about pervasive male homosexuality, were basic to Billing’s defence. Allan was accused of promoting lesbianism and Grein was tarred with charges of homosexuality; ultimately Allan lost in court. ‘If one of the consequences of the Billing case is to give new value to the ancient virtues’, editorialized the London Times, ‘then there may be some compensation after all for the work of a scandalous week’.

Questions about Sassoon’s sexuality circled among London’s cognoscenti in later years. Writing to her nephew Quentin Bell in December of 1933, Virginia Woolf (who had reviewed Counter-Attack favourably in the Times Literary Supplement) wrote of the circle of young male acquaintances surrounding Stephen Spender and his live-in-house mate Jimmy Younger – W. H. Auden. J. R. Ackerley, William Plomer, all of whom were, according to Woolf, ‘wearing different coloured lilies’.

Their great sorrow at the moment is Siegfried Sassoon’s defection; he’s gone and married a woman, and says –Rosamund [Lehmann] showed me his letter – that he has never till now known what love meant. It is the saving of life he says; and this greatly worries the Lilies of the Valley, among whom is Morgan of course, who loves a crippled bootmaker; why this passion for the porter, the policeman, and the bootmaker?

Woolf’s wry response is less opprobrium about male same sex relations in her circle, where they of course were common, than a querulous fascination with such relations across class boundaries, while her repeated reference to lilies evokes one of Wilde’s signature flowers. (The ‘Morgan’ Woolf mentions is the novelist E. M. Forster, two of whose lovers, Harry Daley and Bob Buckingham, were policemen.)

It is difficult not to sustain a sense that throughout his life Sassoon was conflicted not so much about sexuality as about the possibility of public revelation. On 26 March 1921, Sassoon recorded his ambition to write something larger – the great English novel about homosexual experience, what he called

one of the stepping stones across the raging (or lethargic) river of intolerance which divides creatures of my temperament from a free and unsecretive existence among their fellow men. A mere self-revelation, however spontaneous and clearly expressed can never achieve as much as – well, another Madame Bovary dealing with sexual inversion, a book the world must recognize and learn to understand! Oh, that unwritten book! Its difficulties are overwhelming! It must be written by a man free from social limitations; someone who has known joy and sorrow and bitterness, but has won his way into serenity and detachment, but an imaginative and creative condition which can control, and yet feel, the tragedy which he is creating, that others may be wiser. And it must be absolutely free from any propagandistic feeling. It must be as natural as life itself. A Tess created from my own experience! That such a book will be written in English, I do not doubt. This century will produce it. May I live to read it, even though it is by another hand than mine.

In its prophetic ambition and idealism Sassoon’s visionary dream of a novel of homosexual amours that would evoke Flaubert and Hardy’s classic fictions of scandalous, tragic women recalls the romantic fervour about the recognition of (especially the self-recognition of) male same-sex passion that is evident in his youthful letter to Edward Carpenter. Yet later, with characteristic ambivalence and self-torment, Sassoon dismisses such a project. On 17 July 1939, he scribbles over this passage, ‘Nothing would surprise me now. But I am still awaiting the masterpiece. Homosexuality has become a bore; the intelligentsia have captured it’.

Of course, there were many differences between Graves and Sassoon beyond matters of sexuality. Graves was keenly aware that, unlike the financially well-heeled Sassoon, he was a working writer with a growing family to support. Notably, too, Graves did not want to keep writing about the Great War. He only included one poem about the war in his 1955 Collected Poems. All his life Sassoon tried to write of matters unrelated to the war, but he kept returning to it. In yet another fissured triangular relationship in the Graves-Sassoon personal saga, both men became divided in their perspectives on Gosse. Sassoon had given Graves a letter of introduction to the older writer. ‘We had a long and inspiring conversation’, Graves explained to Sassoon. ‘He was an awfully nice man.’ Graves had been especially gratified by Gosse’s praise of his second book, David and Goliath. In 1930, however, Graves dismissed Gosse as a ‘vain and snobbish old man’, someone to whom he had been ‘polite’ for ‘too long’ and who had been ‘backbiting me, to strangers, in his usual grotesque way’.

I shall be glad to become a Gosse, if it means preserving vitality and enthusiasm and hatred of humbug until I am seventy-nine (with a little pardonable – self-defensive –vanity added).

This final rift was influenced perhaps by Graves’s awareness that Gosse had been an advocate for Sassoon, yet another instance of Sassoon benefiting from the privileges of his family’s social connections. The break spoke, too, of Graves’s longstanding sense that Sassoon was beholden to literary niceties, distortions, and pretences, dependably status-conscious to a fault. In fact, anxieties about exactly those matters animate the 1918 verse-poem, the first line of which marks a repeated caustic self-reproach about orchestrated fame: ‘I’d timed my death in action to the minute | The Nation with my deathly verses in it).’

In the last lines of the ‘Dear Roberto’ poem there is a striking shift into direct address, a break into epistolarity elsewhere absent in this ‘epistolary poem’. After his confession of dissident desire – ‘And they’ll say what lovely faces were | The soldier lads he sang’ – the speaker turns directly to Graves. ‘Does this break your heart?’ quickly followed by a defensive hauteur – ‘What do I care?’ The final lines aim at a Roberto held, perhaps, far too dear.

The author would like to thank the Berg Collection at the New York Public Library, the Beinecke Library at Yale University, and Rutgers University Libraries for the help of their staffs in researching the material discussed in this essay.

Richard A. Kaye is Professor in the Department of English at Hunter and in the Ph.D. Program at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York (CUNY). He is the author of The Flirt’s Tragedy: Desire without End in Victorian and Edwardian Fiction (2002) and the editor of The Picture of Dorian Gray in the Twenty-First Century (2025). His essays and reviews have appeared in Modern Fiction Studies, Studies in English Literature, Victorian Literature and Culture, Modernism/Modernity, The Wallace Stevens Journal, English Literature in Transition, and Modern Language Quarterly. He is the editor of the D. H. Lawrence Review.

NOTES

Unsigned Review, ‘Georgian Poetry’, Times Literary Supplement, 27 December 1917, p. 646.

Contemporaries (Spring 1994).

(London: Faber and Faber, 1983), p. 108.

Graves’ blunt characterization of his former friend may have been in part defensiveness about his own sexuality; four years earlier, in a BBC television interview with Malcolm Muggeridge broadcast on November 16, 1965, Graves was repeatedly asked about what Muggeridge called Graves’s ‘homosexual phase’ at Charterhouse, a characterization that Graves, visibly exasperated, denied with an equally blunt response: ‘I am not a faggot myself.’ Explaining Charterhouse, Graves explained, ‘If you keep boys away from girls then you get homosexuality’, and went on to cite Shakespeare’s Sonnets in which, Graves explained, Shakespeare was in love with a woman but then a man is introduced into the scenario and the ‘whole thing ended in tears’.

(London: Secker and Warburg, 1984), pp. 464-65.