|

Search Help |

|

Links Robert Graves Website Other RG Resources |

Critical Studies

Collaboration & Adaptation: Laura Riding & Robert Graves’s ‘Greeks and Trojans’

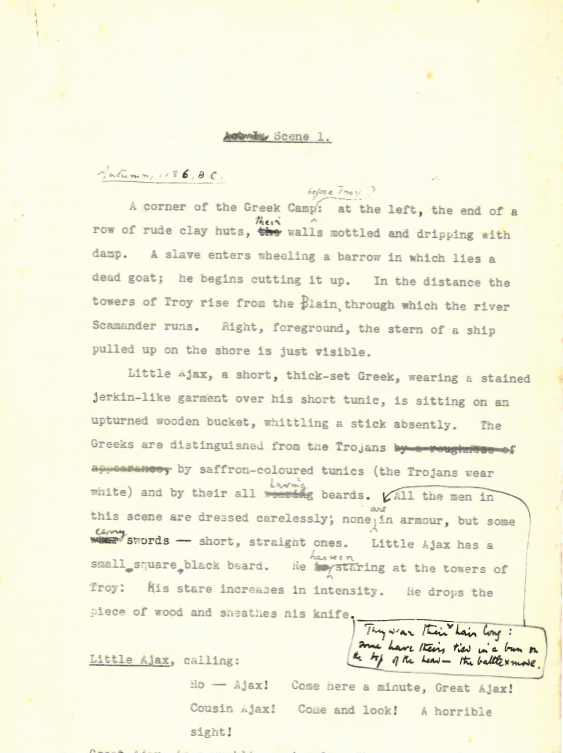

Riding’s edits note the scene’s season and date and appear fainter while Graves’s appear in a boxed insertion and are more darkly inked.

Collaboration & Adaptation: Laura Riding & Robert Graves’s ‘Greeks and Trojans’

The problem of determining the true story of Troy is not one for the scholar at all. It is a poet’s problem, requiring a delicate balance between a sense of the past and a sense of the present—since a story of past events must include the present from which they are viewed.

Abstract This article reports on the recent recovery of a screenplay, ‘Greeks and Trojans’ (c. 1937), which is based on Laura Riding’s historical novel A Trojan Ending (1937), adapted for film by Robert Graves, and which enlarges the corpora of both Riding and Graves. Background is given on Graves’s commercial venture with London Film Productions founder and producer Alexander Korda, the aborted filming of I Claudius in the 1930s, as well as Korda’s interest in the ‘Greeks and Trojans’ project. The essay gestures to continued contemporary public interest in Graves, Riding, and the Trojan cycles.

Keywords: classical revisionist studies, literary adaptations, cinema studies, Trojan War

_

The colorful history of the literary partnership of Robert Graves and Laura Riding has, of late, become something of a screen sensation. William Nunez’s 2021 biopic The Laureate won Film of the Festival at the 2021 Oxford International Film Awards as well as Best Feature, Best Director (Nunez), and Best Actor (Tom Hughes). The Laureate dramatizes an early period in the Graves-Riding relationship, during the mid- to later-1920s, through the depiction of an often-tumultuous love triangle entangling Nancy Nicholson, Graves, and Riding – then, later, Irish poet Geoffrey Phibbs. Graves’s literary legacy has, more importantly, found its way to film through other genres as in the highly successful 1976 BBC Television adaptation of his historical novel I Claudius (1934), with its all-star cast to include Sir Derek Jacobi as Claudius, Dame Siân Phillips as Livia, George Baker as Tiberius, Sir John Hurt as Caligula, Sir Patrick Stewart as Sejanus, and many other now notable British talents.

As it happened, the I Claudius film had been slated for a much earlier staging under contract with Alexander Korda, the Hungarian-British film director, producer, and founder of London Film Productions (1932) and Denham Film Studios (1935/6-1952). Graves’s enormously successful Claudius books had unsurprisingly attracted Korda’s attention, as he had been successful with a run of historical re-enactments, including The Private Life of Henry VIII (1933), The Rise of Catherine the Great (1934), and he was busy filming Rembrandt (1936) during this period in the mid-Thirties. Korda visited Graves in Deià in January 1935 to discuss a contract for the film rights to I, Claudius. He planned for the Austrian American filmmaker Josef von Sternberg to direct the film and to cast Charles Laughton as Claudius, Merle Oberon (Korda’s wife) as Messalina, Emlyn Williams as Caligula, and Flora Robson as Livia. Graves’s March 1935 diary records the projected filming timeline, the signing of the contract, and Korda’s interest in other projects including Graves’s and Riding’s collaborative novel No Decency Left (1932) and a screenplay based on T. E. Lawrence’s life.

Following their evacuation from Mallorca on 2 August 1936, at the start of the Spanish Civil War, and while in London, Graves (and sometimes Riding) visited with Korda at the Denham Studios where Korda expressed interest in additional projects, including a Graves-Riding sketch about Spanish refugees. According to Richard Perceval Graves, Elizabeth Freidmann, and others, the notion for a dramatization of Riding’s soon-to-be-published historical fiction, A Trojan Ending (1937), was Graves’s idea and Korda was receptive to the proposal. Korda’s interest in Riding’s novel’s subject is not surprising as, while working in Hollywood, he had directed the 1927 black-and-white silent film The Private Life of Helen of Troy, an historical romance that made his reputation in the American film industry. Graves soon shouldered the task of adapting her novel to dramatic form.

Filming of I Claudius began in February 1937. Unfortunately, after one month, on 18 March, Merle Oberon was injured in a car accident and the shooting was soon stopped. Many film scholars have lamented this thwarted project, even though there were problems with Charles Laughton’s handling of the role of Claudius. Critic Warren Clements of The Globe and Mail remarked: ‘A truly wrenching what-if was the loss of the 1937 version of I, Claudius, with Charles Laughton as the limping, stuttering, intensely admirable soon-to-be-Roman-emperor Claudius.’

Collaboration & Adaptation

‘Greeks and Trojans: A Play in Six Scenes’ is Graves’s adaptation of A Trojan Ending, Riding’s extensive rewriting of the last year of the legendary battle between Troy and Greece, including the sacking of the Trojan stronghold. In particular, Riding works to redress the infamous or damaged reputations of her chosen subjects: Helen of Troy, Cressida, Cassandra, and even the Trojan army legendarily defeated by the Greeks. Scenes unfold almost entirely in domestic spaces, rather than battlefields, as sites for dramatic action – the palace bedrooms and the viewing tower, presented as alternative seats of power where women might be present and able to speak. Just as Graves reanimated Roman and Byzantine emperors in I, Claudius (1934), Claudius the God (1935), and Count Belisarius (1938) with distinctly modern pathologies, so, too, did Riding imbue her legendary women with contemporary complexities and ambitions in both A Trojan Ending and her other historical novel Lives of Wives (1939).

Riding’s recovery of historical women in her novels as well as in the screenplay adaptation offers an example of feminist re-envisioning of the classical past concurrent with variations proposed by other modernist-period women writers, to include Mary Butts, Naomi Mitchison, Mary Renault (Eileen Mary Challans), Virginia Woolf, and the notable classicist Jane Ellen Harrison, to name but a few examples. These authors ventured creative refigurations and variations on historical narratives – what Riding would later term ‘suppositious histories’ or, as more recently proposed by Saidiya Hartman, ‘critical fabulations’.

Across the period of their working partnership (1926 through 1940) Graves and Riding collaborated on projects and consulted with one another during the writing process for works in draft. Both writers did considerable research for their history projects and Graves provided background notes for both of Riding’s historical novels. Their collaborative spirit extended to the many initiatives that attracted and engaged writers, artists, and intellectuals arriving in Deià to contribute to the dictionary projects, Seizin Press publications, as well as to work on their own books and art ventures.

William Graves, Robert’s oldest surviving son and his literary executor, informed me about the unfinished screenplay now housed in the Special Collections Research Center at Southern Illinois University (USA).

The Afterlife of Scripts

Invasions, wars, conflicts are still much with us and the classical period, including the Trojan War, distinctively, continues to occupy contemporary cultural space. The 2018 BBC/Netflix collaboration Troy: Fall of a City is case in point and already it has generated scholarly discussion: as in the 2022 collection Screening Love and War in Troy: Fall of a City.

A version of this paper was delivered at the Fifteenth International Robert Graves Conference in Palma, Mallorca, Spain, 12-16 July 2022.

Anett K. Jessop is an associate professor of English in the Department of Literature and Languages at the University of Texas at Tyler (USA) where she teaches late-nineteenth-through twenty-first-century American literature and creative writing. Her research and teaching specializations include modernist studies, classical reception studies, poetry and poetics, philosophies of language, feminist and gender studies, as well as Mediterranean and Middle Eastern studies. Recent publications link modernist writing and revisions of classical history, myth, and genre.

NOTES