|

Search Help |

|

Links Robert Graves Website Other RG Resources |

Bibliography

Verses for Margaret Russell

Abstract: This note brings to light an unrecorded poem written by Robert Graves in 1940 for Margaret J. Russell, who had been Jenny Nicholson’s nanny, 1919-1921.

Keywords: occasional verse, domestic life, Margaret Russell

__

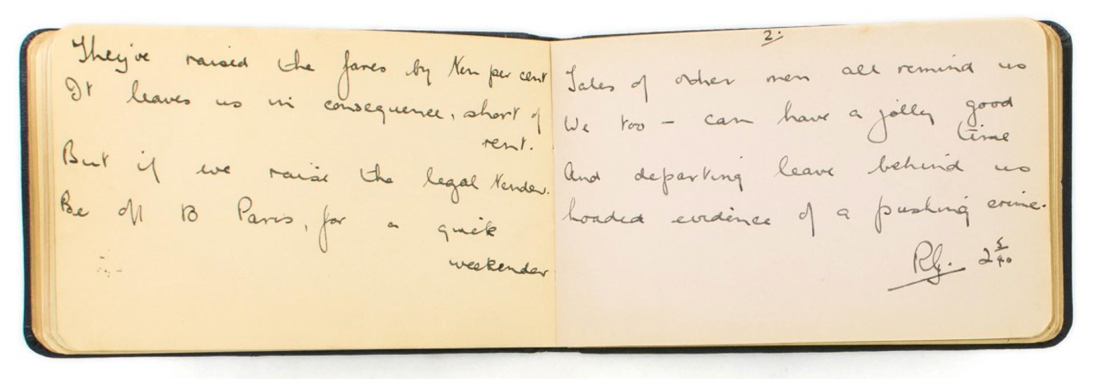

They’ve raised the fares by ten percent.

It leaves us in consequence, short of rent.

But if we raise the legal tender,

Be off to Paris, for a quick weekender.

Tales of other men all remind us

We too – can have a jolly good time

And departing leave behind us

Loaded evidence of a pushing crime.

RG. 2 5/40

The eight-line unpublished poem is written on the verso and recto of facing leaves in a small oblong autograph book that belonged to Margaret J. Russell (née Reed), whose signature appears on the front pastedown.

Miranda Seymour describes Russell as ‘a doting Geordie nanny’.

Two years later, however, in February 1921, Nancy dismissed her for ‘spoiling little Jenny’ (Seymour, p. 100), or perhaps, for failing ‘to follow [...] strict instructions as to diet and daily routine’ for Jenny and David,

Dismissing Margaret took a curious form. Rather than break the news themselves, Robert and Nancy sent her to Graves’s parents in Wales ‘on the pretext of a holiday [...] relying on Amy to hand her their letter of dismissal’ (Wilson, p. 266; Assault, pp. 241-42).

Imagine the effect on Margaret. For two years, Jenny had been the centre of her life, as if she were Jenny’s mother.

Margaret was working at a doll’s dress for Jenny when told of her dismissal; and she cried out: ‘Oh my Jenny! My darling Jenny!’ in floods of tears. APG who witnessed this miserable scene, wrote sympathetically in his diary that evening: ‘I hope Nancy will get as faithful a servant in her place”’. (p. 242)

Despite everything, Margaret remained on affectionate terms with Graves, as the many entries in his diary (1935-1939)

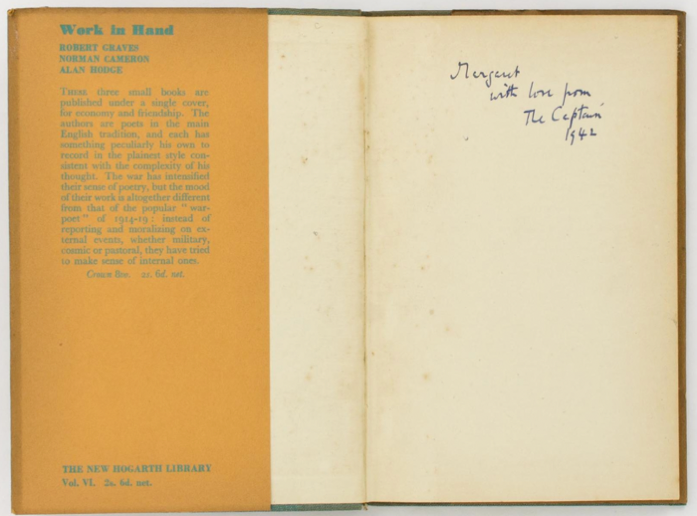

Along the way, Margaret fell into the habit of addressing Graves as ‘Captain’ and referred to him as ‘The Captain,’ the rank he’d achieved in the Royal Welch Fusiliers.

Photograph courtesy of Michael Treloar, Bookseller.

Her surviving letters suggest she was able to speak freely to him and trusted her opinions would be valued. In 1948, soon after his friends Dorothy and Montagu Simmons and their children left England for America to join Riding and her new companion and collaborator, Schuyler Jackson, on their farm at Wabasso to work on the etymological dictionary project,

They have a bungalow near the Jacksons and are now in the throes of grapefruit picking and packing for export ... I feel they have done the wrong move, but I am such a stick-in-the-mud I may be wrong. (R. P. Graves, White Goddess, p. 150)

Margaret was not wrong: the Simmonses were soon scrambling to return home.

In 1941, a year after inscribing the verse in her autograph book, Graves and his new wife, Beryl, re-hired Russell to come to Vale House for ‘five or six weeks’ to help with the housework.

Michael Joseph is Editor of The Robert Graves Review, and Vice President of the Robert Graves Society. Recent publications include ‘How English Poetry Learned to Get Angry after 500 Years of Having a Stiff Upper Lip’, in Emotions as the Engine of History (London: Routledge, 2021), and three poems in Book 2.0 (Spring 2022). ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8117-5739.

Carl Hahn is Bibliography Editor of The Robert Graves Review. He is presently revising and updating Fred Higginson’s bibliography of Robert Graves. Recent publications include ‘The Plague of Modern Scholarship: Theses and Dissertations on the Subject of Robert Graves’ in The Robert Graves Review 1.1 (2021).

NOTES