|

Search Help |

|

Links Robert Graves Website Other RG Resources |

Bibliography

Derick Boothby’s White Goddess

Abstract: This essay is an examination of a signed and bound copy of The White Goddess that once belonged to Major Frederick Boothby, a member of the Bricket Wood Coven, the first modern Wiccan Coven, and a glance at his ten-year correspondence with Robert Graves.

Keywords: Wicca, Frederick Alexander Colquhoun Boothby, Rosalie May Julia Loveday

__

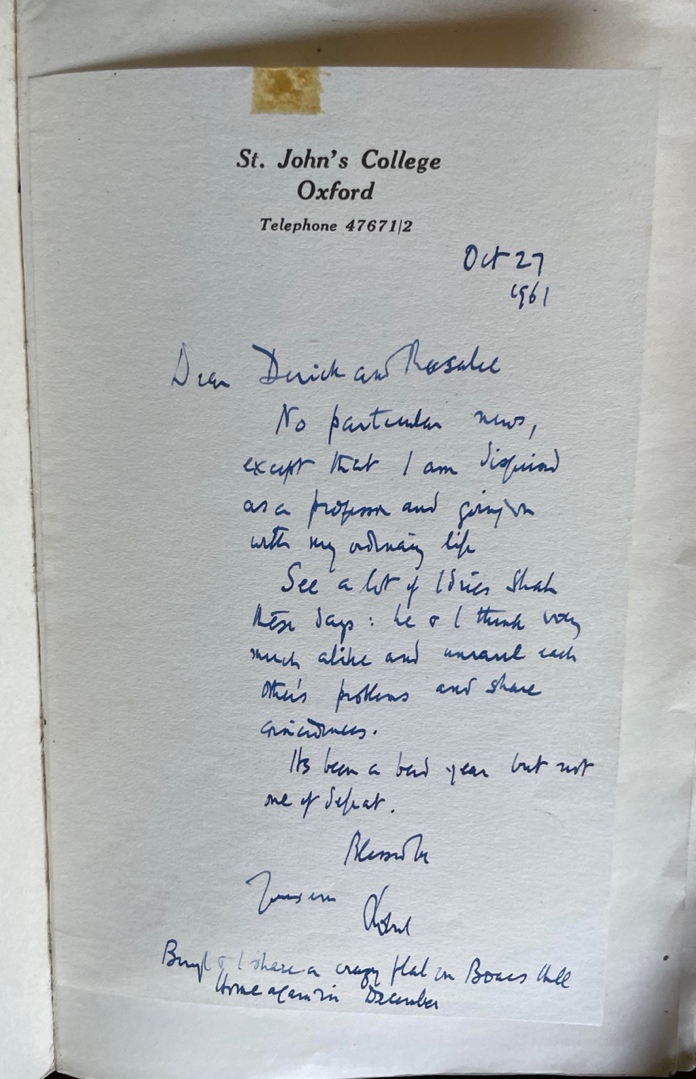

Holograph letter from Robert Graves to Frederick Boothby

and Rosalie May Julia Loveday, 27 October 1961

I had always wanted to own a book signed by Robert Graves. He is by far my favourite poet. His prose stands alone, without peers. His skill at translating, and his unique views of mythology fascinate me. While searching one night for just the right treasure, I came upon a signed copy of the 1961 Faber Paperback Edition of The White Goddess. This was an expanded and enlarged edition, though the publisher was downplaying that fact. Books printed prior to 1966 contain no ISBN. The copyright page simply reads, ‘Faber 1961’. There is a reference to this edition in WorldCat, with the OCLC identifier, 560153136. The original first edition of this work was published in 1948 by Vintage Books with an OCLC identifier of 1319479372. The particular copy I purchased was the 1961 Faber Paperback Edition purveyed by Brimstones, in England. However, this copy was exceptional, rebound in black Moroccan leather with a Yapp edge, in the style of family bibles, and stamped in metallic silver lettering. It was by far the most economical option out of all the signed copies of The White Goddess I viewed. Further, its uniqueness attracted me.

When I opened the package from Brimstones, an envelope containing a letter from William Graves, the author’s eldest surviving son, fell out of the book. The letter was dated 25 April 1996 and written to architect Peter Page (now deceased). Page had written to ascertain the identities of ‘Derick and Rosalie’, the original owners of the book. William didn’t know but suggested perhaps ‘Derick’ was the poet Dereck Savage. He said that he felt compelled to send Mr Page’s letter to the Robert Graves Trust Researcher at St John’s College Oxford to record the existence of the signed copy.

Page was an astute book collector who had amassed over 15,000 books in his lifetime. When he passed away, the first pick of his books went to the Beinecke Library at Yale University, the rest were then sold at auction. Brimstones of England acquired what was left after the auction. As far as I could tell, Page never did learn the identities of ‘Derick and Rosalie’; the responsibility to solve this mystery had fallen to me.

However, the book had not exhausted its store of surprises. Further inspection uncovered a small note written from Robert Graves on St Johns College letterhead to ‘Derick and Rosalie’, dated 27 October 1961.

The title leaf had two unique modifications. Graves had signed the title page in blue pencil, adding in red, ‘Blessed Be She’.

In an email to William, I shared my discoveries and hoped he might have gleaned more information about the identities of ‘Derick and Rosalie’. William kindly and promptly replied on 25 July 2021. He was now able to identify them as Major Frederick ‘Derick’ Alexander Colquhoun Boothby (1 September 1909 – 27 February 1979) and Rosalie May Julia Loveday (dates unknown). When Robert Graves had written to them, Rosalie and Derick were dating, though they subsequently married on 24 July 1965 (Graves’s 70th birthday). Rosalie became Derick’s third wife. Armed with this knowledge and with some assistance from the Robert Graves Society on Facebook, I began to unravel a strange and intriguing tale.

I then discovered Graves had had a lengthy correspondence with Frederick ‘Derick’ Boothby and written a few letters to Rosalie Loveday (revolving around The White Goddess). Boothby had written to Graves on 20 January 1960, introducing himself as the leader of several covens in the British Witch Cult. Between 1960 and 1971, they exchanged more than ninety letters, a significant number of which are held by two repositories: The Ellsworth Mason Collection of Robert Graves, 1917-1975, at the University of Tulsa, Oklahoma,

A Note about The White Goddess and Witches

The White Goddess had a substantial cultural impact on the witchcraft community.

After 1961, the steady trickle of letters Graves received about the book swelled into a torrent. Experts real and self-styled, in archaeology and early Welsh, in runes and classical studies, in witchcraft and pharmacology, wrote to offer ‘corrections’ (often themselves of dubious correctness) and extensions to his theories. (Lindop, p. xix)

Rosalie May Julia Loveday, untitled, 1960

The stature of The White Goddess and its relevance to the Wiccan Community were not lost on Boothby, who was an authentic practicing witch. He was an original member of the Bricket Wood Coven, the first modern Wiccan Coven formed by Gerald B. Gardner.

Graves stated that he was not a witch, nor did he belong to any secret societies. However, Lindop suggests Graves was not averse to Wiccan practices.

By the early 1960s, magicians and witches of several kinds were writing to Graves, and the correspondence was not always one-sided: he seems to have been willing to give advice on matters of ritual as well as on the use of hallucinogens. (Lindop, p. xix)

It cannot be credibly denied that Graves believed that witches were essential to the continued cultural presence of the White Goddess, herself. In a letter dated 12 July 1960, he intimates to Boothby that he has been in communication with Mr William Morris, a New York millionaire appeared willing to finance a film based on The White Goddess. Morris asked Graves what witches had to do with the story, to which he replied: ‘they kept the Goddess Religion alive throughout the Middle Ages in a most historic style’. Graves took Boothby seriously as an authority on witchcraft, and Boothby played up his importance in the religion. In a letter dated 10 June 1960, Graves offers him a part in a witch sequence in this (regrettably) ill-fated film.

In addition to being a prominent witch, Boothby was many things in his lifetime. He attained the rank of Captain in the British Army During World War II.

Rosalie and The White Goddess

Rosalie May Julia Loveday was quite a bit more elusive. In his letters, Boothby tells Graves only that she is an artist whose works have appeared in the Royal Academy of Arts. She is best remembered for her portrait of the Scottish poet Hugh MacDiarmid. Overshadowed by her husband, Loveday was pivotal for me in establishing the provenance of this book and provides us with an interesting sidelight on Graves’s infatuation with Margot Callas.

For the holiday season of 1960, Loveday decided to make an engraving for a Christmas card (which eventually became the card glued to the title leaf of my book). When he saw the card, Graves flipped over it. In his eyes, the portrait was an exact likeness of Callas, the woman he wanted to play the Goddess in the film and his current muse. Characteristically, he refused to believe it was coincidental, and insisted that Rosalie must possess some magical intuition. He requested twelve copies of the card from Boothby, which Loveday graciously provided (letters 3 January 1961–23 February 1961).

It is unsurprising that to Graves’s lovestruck eyes, a portrait of a beautiful woman resembled his beloved; however, in my more objective view, the image on the card does look strikingly like Callas. To date, I have located no other copies of this card at St John’s or the University of Tulsa. The only other reference to it turns up in letters Mason wrote to Derick and Rosalie in 1969 attempting to obtain a copy. Arrangements were mentioned in several letters, and Rosalie apparently sent Mason several copies. There is no record of his ever receiving them and there are no copies in the Mason Collection. The card, with its uncanny resemblances, remains just as elusive as its artist.

Ellsworth Mason

The bulk of the correspondence I consulted resides at The University of Tulsa, purchased from Mason.

The value of this beautifully modified 1961 Faber paperback edition of The White Goddess turned out to be much greater than I expected. It is a living piece of history that is not only integral to the story of Frederick A. C. Boothby, but a unique link to the idiosyncratic, wide-ranging intelligence of one of the greatest poets of the twentieth century. Boothby rightly treasured his copy of the book. In a letter dated 3 May 1970 he says, melancholically, he has grown weary of the world and is putting his affairs in order and composing his will. His last wish is to have the dedicatory poem to the Goddess read at his funeral.

The author wishes to thank The Robert Graves Society on Facebook for research advice, The University of Tulsa, St John’s College, Oxford, and the Museum of Witchcraft and Magic in Boscastle, England for pulling correspondences from their collections, William Graves and The Robert Graves Trust for allowing me to quote from unpublished letters, and Philip Heselton for his knowledgeable advice and research assistance.

Steven Michael Stroud is an independent scholar and researcher. Currently he is exploring Major Frederick A. C. Boothby and his role in shaping mid-twentieth-century British witch cults. He may be contacted via email at stevenmichaelstroud@outlook.com.

NOTES