|

Search Help |

|

Links Robert Graves Website Other RG Resources |

Biography

Poetry and The Olympics, 1968 Mexico, Robert Graves

Abstract: A memoir of Robert Graves’s time in Mexico during the period of the 1968 Summer Olympics and of his friendship and long correspondence with the author.

Keywords: Games of the XIX Olympiad, Tlatelolco Massacre.

__

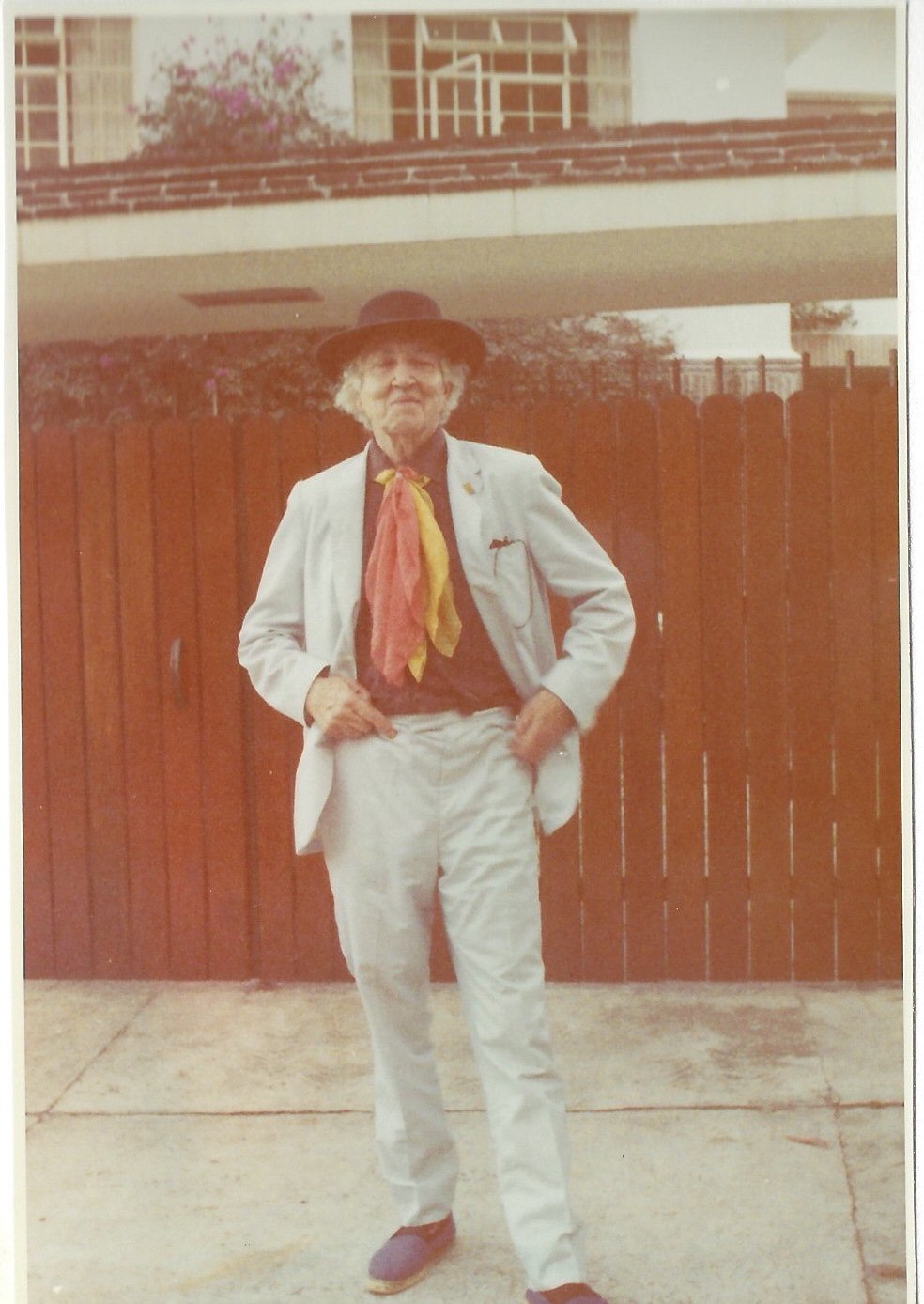

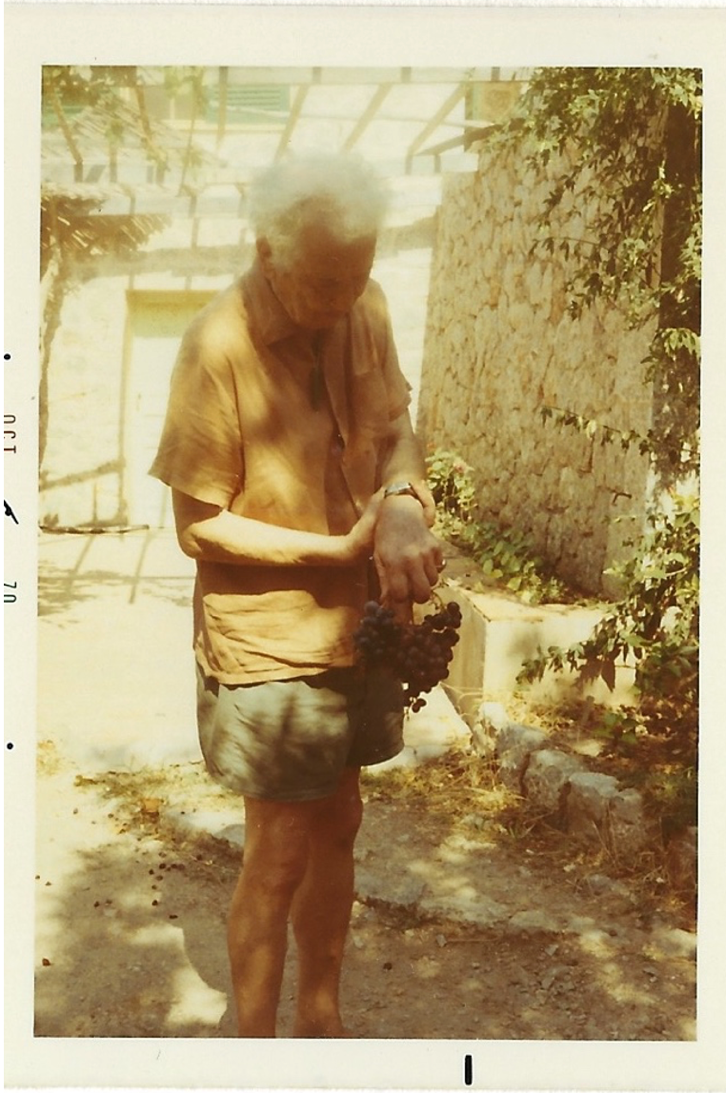

Robert Graves in front of author’s parents’ house in Mexico

First Encounter

He stepped out of the airplane with nonchalance. He seemed aloof and absent minded, attracting attention because of his unusual and picturesque attire. He was very tall, wore shabby clothes and hid his messed-up curly silver hair under a broad-brimmed cordovan hat that covered his brow. His piercing grey eyes wandered through the crowd aimlessly. The crooked nose allowed me to unmistakably identify him as ‘my poet’.

I had come to the airport to welcome Robert Graves, one of eleven poets invited to participate in a poetry symposium organised within the cultural program running simultaneously with the 1968 Olympic Games in Mexico City. I just graduated that summer from Bryn Mawr College in Pennsylvania and had returned to Mexico to my family. Having been away for several years, I was anxious to get involved in the exciting moment of the Olympic Games before going on to graduate school. The eyes of the world were on Mexico, and I wanted to be part of it!

The cultural program organized by the Mexican Government together with the Games was my door of entry. I applied for a position at the Olympic Committee and to my surprise, Oscar Urrutia, the person in charge of the program encompassing nineteen cultural events, asked me to help organise the poetry symposium. My double major degree in Spanish literature and sociology gave me ideal credentials for the job. The idea was to invite all participating countries to have a poet write a text specifically for the Olympics, as well as to bring eleven renowned poets to Mexico to meet one another and participate in roundtables and other cultural events during their stay.

My first task was to collect an anthology of verses paying tribute to the occasion and to prepare brief biographies of each of the guest poets. Aspiring to be a bit more ambitious, I decided to acquire some of their works and was busy making a selection of clippings based on my readings for future press releases. It was a laborious job, but I learned as much as I could about the authors before their arrival and became familiar with their writings.

Russian dissident writer Yevgeny Yevtushenko had visited Mexico several weeks before, at the time of the Prague Spring. He had drawn large crowds of young Mexicans with his message of freedom and lofty social ideals. His visit had been somewhat polemic, making the Mexican authorities anxious about his possible influence on student protesters who were already on the streets of Mexico City as part of the 1968 movement.

Robert Graves, representing England, was the first on my list to arrive. Robert Graves’s writing was apolitical. His poetic contribution to the Mexican Cultural Olympiad was to be an ode to Enriqueta Basilio, the first woman ever chosen to carry the Olympic torch and light the flame for the opening of the Olympic Games.

I approached our visitor to explain who I was and that I was to take charge of him during his stay in Mexico. He acknowledged my introduction, and we moved through to an immigration desk. My first problem was to get him into the country without a visa. He had simply neglected to get one and I was finally able to convince the officer that he was a special guest of the Mexican government. We collected his luggage and walked to the exit.

My second problem appeared as we stepped out of the terminal. A good-looking woman rushed over to intercept us before we could get into my car. She pushed me aside, hugged ‘Robert’ and declared that she was taking him off to Santa Clara del Cobre in Michoacán to spend the few days prior to the Olympics in the company of good friends of his who were expecting him. She assured me he would eventually come back in time for the opening ceremony.

I became upset. At all costs, I had to keep him with me and not have him disappear into unknown territory before his appearance at the Games. After that, he would be free to go wherever he pleased. I insisted that he must stay in Mexico City because he had no local currency and I needed to sort that out once he was settled at his hotel. The ‘intruder’ reluctantly agreed to let him remain in my custody and offered instead to host us for dinner at her home the following evening.

On our way to the city, Robert explained that the mysterious interloper was Pilar Pellicer, a famous Mexican actress, married to an old friend of his, James ‘Jimmy’ Metcalf, a sculptor who had made his home in Santa Clara because of the abundance of copper in the region. Jimmy and Pilar had visited Robert in Mallorca right after the war.

Our first conversation led me to understand a great irony: he had accepted the invitation to the poetry symposium only as an excuse. His real reason for coming to Mexico was to join his friends in experimenting with the local varieties of mushrooms and to walk through the ‘doors of paradise’. He had already been exposed to the effects of mushrooms on a former trip to Mexico, but then the doors remained shut. On this occasion however, he was convinced they would open, allowing him to enter and reach his nirvana. It sounded like a farfetched fantasy, but he was obsessed with carrying out this mission and I had to come up with an alternative project, lest I should lose my poet in his wild dreams of goddesses, mushrooms and adventures.

Getting Acquainted

My task was to keep him busy by interesting him in Mexico’s rich cultural history. I organised a visit to the famous Museum of Anthropology designed by Mexican architect Pedro Ramirez Vazquez. It displayed a fabulous collection of idols and sculptures from the Maya, Aztec and other pre-Columbian civilizations.

As we walked through the rooms dedicated to the various Mesoamerican civilizations, he contemplated the works of art in silence. An outburst of comments followed. He drew parallels with the gods he knew from other polytheistic cultures and with the many concepts he could extrapolate from the classical world of the Greeks and the Romans with which he felt closely connected. He was intrigued with the female goddesses and the intricate rites of fertility surrounding them. A matriarchal society had existed in all these cultures and the female figures he saw at the museum coincided with his belief in the White Goddess who, like the Greek Hera, was the origin of human life.

A journey to the pyramids of Teotihuacan the following day awoke memories of the time he had spent teaching at the Royal Egyptian University in Cairo. He referred to legends and rituals and then began narrating stories with great enthusiasm, in a stream of consciousness. I had difficulty understanding him. He spoke rapidly, in a stilted speech, referring with familiarity to legendary characters from the past, whom he had made part of his inner world while considering them his best friends. I was fortunate to have had a classical education and could thus follow, or at least pretend to understand his complicated discourse.

I must have made an impression on him for he commented on the pleasure he felt in addressing an educated listener. At some point, I mentioned my Bryn Mawr background and the school’s symbolic icon: the owl, a bird of wisdom whose huge eyes stare into the night absorbing and reflecting knowledge. The very next day, he handed me a handwritten page with two poems related to night owls that he had recently published, ‘Arrears of Moonlight’ and ‘Like Owls’.

Like Owls

The blind are their own brothers, we

Form an obscure fraternity

Who, though not destitute of sight

Know ourselves doomed from birth to see,

Like owls, most clearly in half light.

I had the feeling that his gesture was a mark of approval. In the many letters he would later write, the owl theme always appeared somewhere on the page. On 21 October 1968, he headed the letter, ‘Wanted: owl eyes!’ On 15 November 1968, he mentioned that someone wanted to reissue a magazine he published in 1920 called The Owl and signed off ‘love to Bryn Mawr!’

Although no longer young, he still emanated incredible energy, which expressed itself as a will to share knowledge and to encompass the whole universe in every sentence. I was dazzled by the strength and the power of his rhetoric. He was physically vigorous and climbing up and down the Teotihuacán pyramids was easy. The result was the most dynamic combination of simultaneous thought and action in a single stroke.

Since I did not have a budget to entertain him for a whole week, I invited him home for lunch. I was living with my parents and figured he would appreciate a more intimate gathering where he could learn about another aspect of the Olympics. My father was the representative of the Omega brand of watches in Mexico. The firm had won the concession for timing the Games and my father was responsible for the process. There was new technology available: the industry had developed highly sensitive instruments that allowed for all sport results to be much more precise than before.

An improved technique for taking pictures permitted judges to record precisely each individual’s performance.

Robert became very excited listening to how the timing would function. It was like a jigsaw puzzle to him: all parts had to fit perfectly together. He knew many details about the Olympic Games and how they were organised in classical Greece every four years, but he had no clue how to run a modern Olympics with complicated technical advances. He asked question after question, and I felt relieved. I had succeeded in keeping him interested.

The following morning, we drove to Tepotzotlán, north of Mexico City, to visit a magnificent sixteenth-century late baroque monastery and its gilded altar, an example of the ornate churriguresque style that flourished in Mexico during the Spanish colonial period. He showed less interest in this as he was not a fan of the period and had an aversion to churches. His maternal family of German origin were Saxon country pastors and he had bad memories of his mother’s push to have him attend religious services against his will. Visiting a convent was not his cup of tea.

However, after seeing the altar, he asked to go outside, through the cloisters leading to a courtyard with a small vegetable garden and an orchard. Here he was more in his element. He picked the shoots of a few plants, gathered some leaves, and then turned his attention to the wild roses. With a certain pride, he pointed out different species accompanied by their Latin name and place of origin. He then went on to indicate how hybrids were bred and later selected, relishing narrating to me the symbolism behind every flower, as well as its connection to particular Greek gods and goddesses (e.g. roses were identified with Aphrodite, the goddess of love), while he attributed other associations to the rest of the flora. He pointed out each species to demonstrate how many he recognised at a glance. He knew his plants and was delighted to give plenty of explanations. Discovering vinca per vinca (periwinkle) in the cloister was a great joy for him. He would write later:

The song was about the vinca-per-vinca, or periwinkle, the fiore de morte, not the fennel (one eats). I love fennel. We use it for pickling our olives. Feneuil is the word here. Fennel stalks were used in the Greek Islands to carry the spark of fire in their pith […] Feneuil mari ‘sea fennel’ is samphire pickled here as in King Lear’s day.

Several other letters refer to his gardening activities, to his yearly preparation of quetsche and crab apple jam in Deyá. Often he combined these references with mythological elements. For example: 9 April 1969. ‘I have planted my pre-Columbian maize goddess beside my maize potato and expect her to help – I should also have got [sic] a potato goddess’. And 4 August 1970: ‘An agave next door is just doing its star-turn of flowering and death, with countless bees as attendants. Mine did that two years ago after 40 years.’ In another letter he said he would have liked to send me some of the flowers that were blooming in all their splendour in his garden, but flowers ‘travel badly’.

As we walked around the convent gardens, I listened in awe. There might have been a hint of flirtation as he spoke, but it didn’t go beyond that. He used figures of speech that were not offensive, and it didn’t occur to me that the elderly poet of love might have been pursuing me. I was flattered by his words, but focused on his passion for wildflowers, nature and gardening. I understood his preference for the outdoors as the main reason for his decision to live in Mallorca.

When we returned to the city, I suggested having lunch the next day with my parents’ neighbours and closest friends. I thought he would be interested in meeting Dr George Rosenkranz, a Hungarian organic chemist who had emigrated to Mexico and researched producing natural steroids from yams that were found in remote parts of Veracruz state. He had started experimenting with cabeza de negro, a black head yam, but had quickly replaced it with a related plant, barbasco, the root of which yielded hormones for the production of highly innovative drugs. In 1959 he had created the first synthetic contraceptive pill that led to fertility regulating treatment for women.

Robert was thrilled to learn about the properties of these yams. He intuitively understood the immense benefit the world was to derive from this scientific discovery. Women would be free to decide when they were ready to bear children. Their role in society would change as they attained new freedoms. For the first time, they could aspire to be on an equal footing with men.

He was enthralled with what he had learned. He cancelled plans to see his Morelia friends and the hallucinatory experience he had expected to undergo with ‘magic mushrooms’. He only wanted to learn more on the subject of the pill. Both lunches had been a success.

Oct 21st 1968

Just to say I got safe back after an adventureless voyage. All well at home... Home food tastes differently good, but of course the cooking can’t claim comparison with the Holzer cooking, or even the Rosenkranz and Urrutia sort, which is pretty good too.

During the considerable time we spent together, I was able to overcome my youth and naiveté, and Robert was pleased with the attention he was getting. He had become a friend and not just the famous writer I was to present at the Cultural Olympiad. The political turmoil that followed because of student unrest in the city, and the resulting climate of unexpected instability, strengthened the bond between us.

Activism in Mexico

In 1963, the International Olympic Committee selected Mexico to host the XIXth Olympic Games, beating out Detroit, Lyons and Buenos Aires. At the time, the country was blessed with economic and political stability and experiencing a boom labelled ‘the Mexican miracle’. The challenge to the country as host of the Games was to build stadia, athletic housing, rapid transit infrastructure and other massive construction projects that would show Mexico, the first developing country to host an Olympiad, to be an ideal site and the nation would benefit from the publicity and tourism that followed.

1968 was a moment of global change and uncertainty. France, Italy, Czechoslovakia, the United States and now Mexico were all faced with student protests and violent demonstrations triggered by a desire for more freedoms and a rejection of authoritarian systems of government. There was an underlying yearning to transform the status quo. The student-led uprisings in other parts of the world had inspired Mexican counterparts to take advantage of the coming summer Olympics to pressure the government to meet their demands. The government wanted to showcase an image of efficiency, coordination and optimism at all costs, and to dismiss those who were made apprehensive by student unrest and street violence in the Spring of 1968.

This change in mood and the constant confrontations between students and authorities darkened the festive impression of Mexico that had been instrumental in its selection as a site for the Olympics. The unrest gained momentum. There were street fights, barricades, confrontations with the police and other demonstrations that made headlines around the world. People began to question whether Mexico was ready to receive the thousands of athletes, media representatives and tourists.

In addition, many Mexicans began to question whether the cost of hosting the events was too high for a country with extreme poverty. While the unrest continued to grow as the date for the inauguration approached, two massive marches to the main square in Mexico City (The Zócalo) on 13 August brought out between 150,000 and 300,000 demonstrators; a second march two weeks later, half a million. It was planned as a silent demonstration and promised to be non-violent, but some students entered the nearby cathedral, rang the church bells and shouted insults towards the presidential palace (Palacio Nacional) in front of them.

President Díaz Ordaz decided that the disturbances were harming the country’s image. He threatened to respond more aggressively to future demonstrations. The International Olympic Committee (IOC) began to consider cancelling the Games.

The Government tried, unsuccessfully, to impede media coverage of the disturbances but the situation had gotten out of hand. Demonstrations increased in subsequent weeks and the world saw Mexico City racked by violence, with an ineffectual police force unable to guarantee safety. On October 2nd, a largely peaceful concentration in the Plaza de las Tres Culturas erupted into armed confrontation between the military and unarmed protestors; Mexican armed forces fired on the protesters resulting in numerous deaths.

Bowing to pressure, Díaz Ordaz cancelled the poetry symposium I was organizing. Nevertheless, he believed that the general unrest might result in a symbolic figure who would be supportive of the student demands and dreaded the possibility that one of the invited poets might assume that mantle. They were all world-renowned figures with high visibility, many of whom had supported similar causes abroad. He needed no foreign heroes to further inflame the situation.

I quickly made the appropriate changes and presented apologies to those who had been invited but had not yet arrived in Mexico. Among my group of poets: Odysseus Elytis of Greece had become ill and cancelled. León Felipe, who had organized weekly poetry recitals in Chapultepec Park as part of his contribution to culture in the city, died just a few days before the scheduled opening of the Symposium, and Bobi Jones, the Welsh poet who did make it to Mexico, had to be hospitalized soon after his arrival with food poisoning. Robert was already in Mexico, eager to participate in a Symposium that no longer existed. Without the symposium, I needed to arrange an agenda to keep him busy until the Games.

A New Approach: Socios

I sought the advice of my old philosophy professor, Dr Ramón Xirau, a Catalan exile from the Spanish Civil War, who was very well connected in the intellectual milieu. He suggested organizing readings in private homes, at cultural centres in and around Mexico City, at the British Council, at the Spanish Embassy, at the Anglo-American Cultural Institute and at Bellas Artes. People would attend these events by invitation only. Dr Xirau also put me in touch with members of the Mexican intelligentsia, including Agustín Yáñez, Jaime Torres Bodet, and Salvador Novo. I was very happy to receive a positive response from all of them and some even suggested hosting dinners and lunches at their homes.

Several other less well-known writers had appeared in town having heard about the poetry symposium. There was Octavio Amórtegui from Ecuador; Jorge Luis Morales from Puerto Rico, Franklin Morales from the Dominican Republic, Miguel Gomez Checa from Peru, William Howard Cohen, an activist poet from the United States, and some younger writers from different parts of Mexico. They had appeared at my office to make their presence known and to ask for inclusion in the official program of cultural events. They gave me examples of their work and by the end I had collected a stack of their literature. I agreed to add their poems to the printed anthology I was putting together. Although I hadn’t planned individual readings for any of them, I decided to add them all to the program and in this way, at least, to have a larger group of writers.

Robert listened in silence as I explained this turn of events and what I was asking of him, then shared his concern about the gravity of the situation in Mexico and his sorrow at the cancellation of the Symposium. He kindly agreed to the Xirau proposal. As we spoke, he picked up a book of his collected poems which was lying on my desk with my name on it and with a smile added his own after mine, followed by the word socios (partners).

After Tlatelolco

Despite the Tlatelolco tragedy, Avery Brundage, President of the IOC declared that the Games would go ahead: The Mexican Government was guaranteeing an end to the violence and preparations were already far advanced. Mexican intellectuals disagreed with the decision. They believed that Tlatelolco was a major violation of human rights. They demanded that Díaz Ordaz cancel the Games. The most vocal critic of the Government’s policies was Octavio Paz, who had abruptly resigned as Mexican Ambassador to India in protest on hearing of the massacre. In his famous resignation letter, he stated that although he had originally been invited to the poetry symposium, he had not contemplated attending, nor writing anything on the subject of the Olympics. However, in a gesture of protest against what had occurred at Tlatelolco he had changed his mind and would now write a poem condemning the tragedy.

The poem appeared in the cultural supplement of the leftist magazine Siempre on October 30th, a few days after the end of the Olympiad. In it, Paz severely criticized the Government, both for the way it handled the demonstration and its attempts to cover up the bloodshed and deaths.

Although Ordaz claimed (falsely) that the Ambassador had been fired, Paz’s poem and his public gesture against the Government made him the protest symbol Ordaz had tried to avoid.

My New Associate

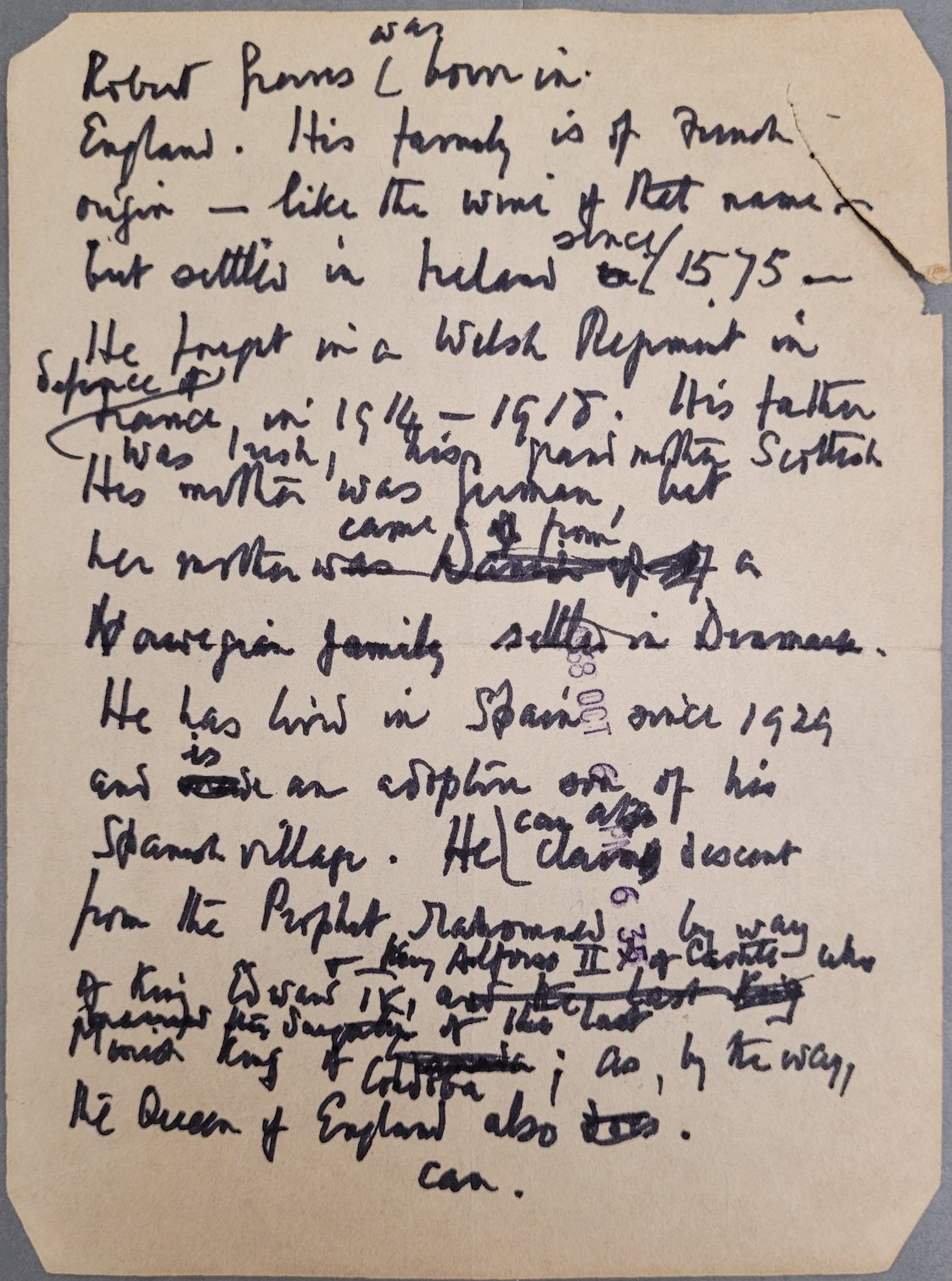

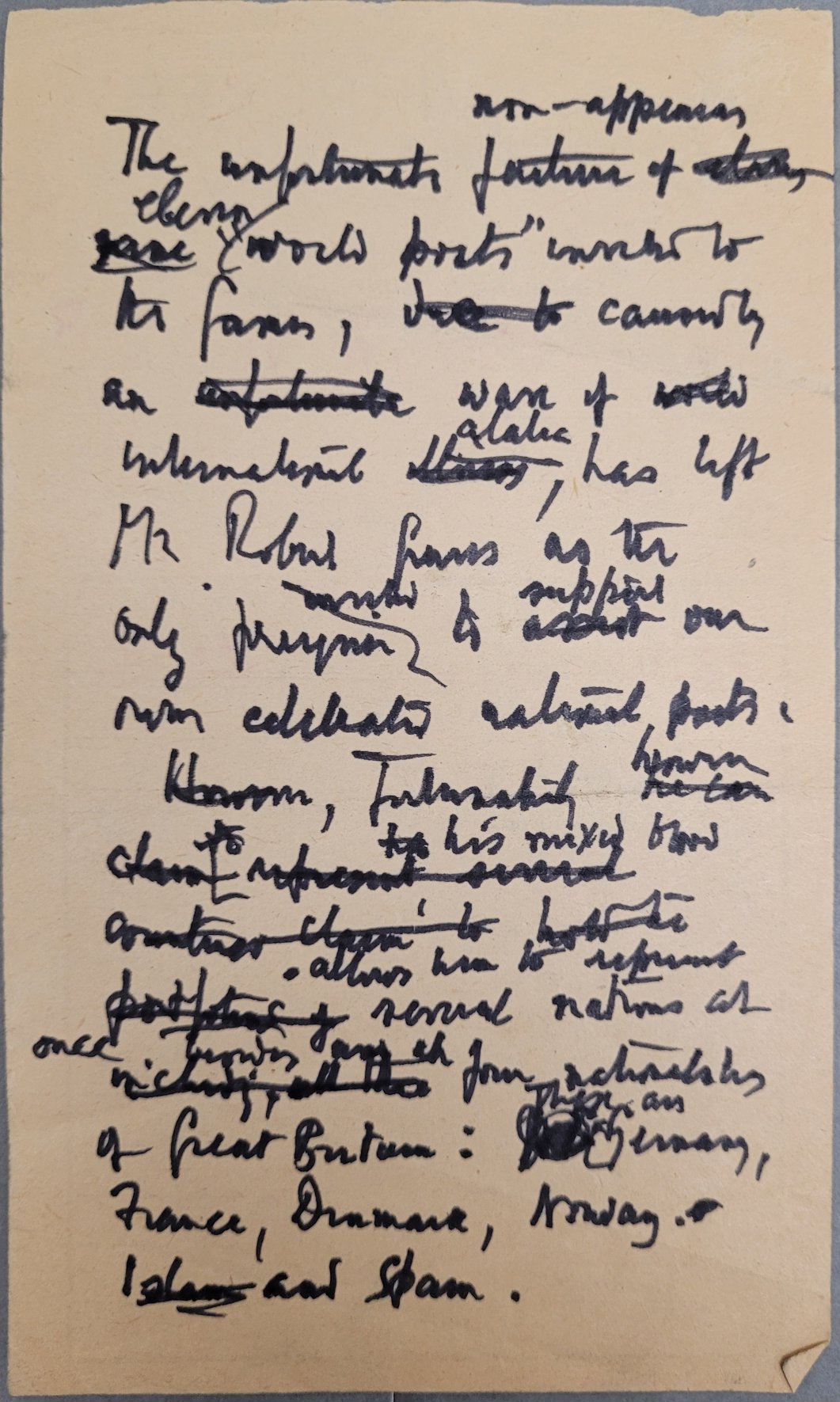

Hours before the massacre on October 2nd, I took a busload of the visiting poets to a United Nations Youth Camp in Cuernavaca. Robert had agreed to tell us about his life and read poems in front of a very international young audience. He was used to this kind of event, and he immediately started telling us how he wanted it organized and how he wished to be introduced. He thought the biography I had prepared was too long, and conventional. He grabbed a scrap of paper and wrote down what he wanted to say.

Robert Graves was born in England. His family is of French origin – like the wine of that name – but settled in Ireland since 1575.

He fought in a Welsh Regiment in defence of France in 1914-1918. His father was Irish, his grandmother Scottish. His mother was German, but her mother came from a Norwegian family settled in Denmark.

He has lived in Spain since 1929 and is an adoptive son of his Spanish village. He can also claim descent from the Prophet Mohammed by way of King Edward IV and King Alfonso II of Castille, who married the daughter of the last Moorish King of Cordoba, as by the way the Queen of England also can.

The unfortunate non–appearance of eleven ‘world poets’ invited to the Games caused by a wave of international clamor has left Mr. Robert Graves as the only foreigner to support our own celebrated national poets.

Fortunately, however, his mixed blood allows him to represent several nations at once. Besides four nationalities of Great Britain; these are Germany, France, Denmark, Norway and Spain.

Corrected biographical introduction, pp. 1-2. St. John's College, Oxford

He had an impulse to jot down whatever crossed his mind, and I began to collect these short notes in a folder. Sometimes there was a story attached, but mostly he would write down a few simple words with his fountain pen, omitting verbs and leaving half of the idea to be inferred. He covered the paper in all directions as if he were writing himself an aide-mémoire that only he could understand.

Love and The Poet

As on other occasions, Robert chattered non-stop in the bus all the way to Cuernavaca. He interacted briefly with the young Mexican poets in the group (Leopoldo Ayala, Jaime Sabines and Alejandro Aura), as well as with Carlos Bracho, the actor who played a role in the readings, but mostly he spoke to me about his life experiences. He told me about his muse, Julie, a young dancer from the Norwegian Ballet, who was his sixteen-year-old goddaughter. According to Robert, she was responsible for discovering the magic that existed between them. In turn, in accordance with the medieval tradition, he played the role of the knight. He had to praise her beauty and bring presents from his travels. He went into a long description of his muse, which in subsequent letters he elaborated on:

19 December 1968:

I went to Norway – which I loved – to see my goddaughter Julie who is in the Royal Norwegian Ballet and with whom I have – as I think I told you – a curiously magical relationship which we accept but cannot explain. Fortunately she first became aware of it so I can’t be accused of anything like cradle snatching. Besides, she remains a virgin, which is unusual these days. You’d love her, because she’s the quiet sort like you – though highly uneducated like all dancers.

His letter raised many questions in my mind. Was it possible that at his age love had a different meaning? Could he establish a ‘magical relationship’ with the muse and yet be able to abstract it from the physical urges he had experienced for other women? Comparing me to his muse, on the other hand, was a compliment.

Another incident also raised my curiosity. While talking about his muse, he was suddenly distracted by the figure of a very handsome younger man who was sitting next to us. He was an Italo-Mexican poet, Claudio, with the perfect features of a Greek god. Claudio had inscribed a book of poems to me and handed me a copy on the bus. The young man’s physique attracted Robert and he started a conversation. Several of his letters to me after he left Mexico referred to Claudio, often asking me about his whereabouts. I wondered if meeting Claudio brought back memories of a tormented attraction, he had felt for a younger classmate in his school days. The idea of a possible homosexual experience had haunted him ever since and as he explains in his autobiography, Good-Bye to All That, the occurrence had profoundly marked him. Another interpretation might be that Claudio reminded him, perhaps at the subconscious level, of Claudius, the Roman Emperor and hero of his novel I, Claudius.

While in his Olympic poem Octavio Paz condemned the Tlatelolco massacre, I believe Robert would have gone further, but as a foreign visitor to Mexico, he refrained from taking a public stance. Privately he told me that the protests could perhaps have been placated through more dialogue with the students. While Paz denounced the government’s indifference, Robert would have asked for more sympathy.

A few weeks later, back in the United Kingdom, he received from the Queen a gold medal for his poetry. On December 19th, 1968, he wrote to me about his audience with Her Majesty, during which she asked him how he came to write his poetry, and he told me, ‘I said it was basically the same magic she uses: one reflects back the love one gives’.

My Ally

We returned from Cuernavaca in time for a splendid dinner organized by Ramón Xirau, who introduced us to several of his friends. We heard that there had been new troubles in town, although nobody knew the details. There had been fatalities during a large demonstration in the Plaza de las Tres Culturas, opposite the Foreign Ministry. At the time we had no idea of the magnitude of what had occurred.

Robert remained quiet in deference to the Mexicans present, but he understood that the situation was perhaps more complicated than it appeared in the light banter of a dinner conversation. He listened to what others were saying. At the end of the evening, I accompanied him to his hotel, somewhat worried that the conversation might have discouraged him from staying on in the country, but he kept his word.

We continued our grand tour of poets in scattered sites around Mexico City. In the days that followed, we had a recital at Oaxtepec, a recreational park an hour away from the city and a second one at the Palace of Fine Arts in the historical centre of the city. There was a reading by the Colombian poet, Octavio Amórtegui, at the Club de Periodistas with Bonifaz Nuño and Andrés Henestrosa. Then a lecture on poetry and lyrics (los poetas y el mar) at the Galería de la Ciudad de México in the Alameda Central on the topic of nature, the environment, and its relevance to poetry. In the evening a cocktail at the Anglo-American Cultural Institute allowed us to meet the Welsh poet, Bobi Jones, who appeared for a moment before being taken ill to the hospital.

There were poets all over town. They appeared in the press, were interviewed and showed up at social gatherings where they discussed issues of the day. There was a fair amount of press criticism because none of the public conversations were about the liberal ideas the activist poets espoused in their verses. We had a feast of words and poetry in the city, but it was disconnected from the political turmoil Mexico was going through.

Robert was pessimistic about the future. He worried about tensions in the world, about United States politics and about the political unrest surrounding the Olympics. He had a gloomy hunch that things would not get better. The oppression he had witnessed in Mexico scared him, and in his speculations came near to predicting the dystopia that would characterize the world we have now. He returned to these worrisome topics over and over in his letters.

One day he saw that I was carrying a copy of his autobiography Good-Bye to All That and asked me if he could inscribe it. Next to my name on the Ex Libris, he wrote ‘Vivian Holzer + Robert Graves’. The inscription made me smile. He had become my true socio.

Opening of the Games of the XIX Olympiad

The date for the opening of the XIX Olympiad finally arrived, October 12th. As if by magic everything was ready and in place. It was a beautiful sunny day, the sky was clear, and the Olympic Stadium glittered in all its glory. The crowds approached the venue in perfect order, following the signs that led to the entrance and to the assigned places. There was electricity in the air. Expectations were at their highest. The white flag with the Olympic logo stood like a sentinel at the centre of the stadium next to a podium where three figures were to address the public: President Díaz Ordaz, Avery Brundage and the President of the Mexican Olympic Committee, Pedro Ramirez Vázquez.

Robert and I were given VIP seats in the immediate vicinity of the stairway leading to the Olympic flame. After the welcoming speeches, the slim figure of Enriqueta Basilio, clad in a white short and T-shirt with a white band around her head ran into the stadium, the Olympic torch held tight in her extended fist. Watching her, I could appreciate Robert’s comparison of the swift-footed Atalanta in his poem, which he would read the following day at the Olympic Village, with Enriqueta Basilio as the main invited guest.

Robert and I had long conversations, both during the Games and afterward in our correspondence, about what the Olympic Games represented for the ancient Greeks and how things had changed in modern times.

An Olympic Poet Laureate

The Olympic Games came to an end on October 27th. Together, Robert and I recalled the best moments, the colour, the camaraderie among people from so many countries, and the many experiences we shared. We tried to put aside the event at Tlatelolco and the student unrest, though their shadow hung over us and remained in our memories for years.

To bring Robert’s stay in Mexico to a happy close, I decided to organize an informal lunch at my parents´ home with some of the Mexicans involved in the cultural part of the Games and several family friends: Oscar and Elena Urrutia, Ramón and Ana María Xirau and a few members of the intellectual community.

Even though the Poetry Symposium, as originally conceived by the Organizing Committee had been overshadowed and then scrapped by political events, Graves kept a positive attitude throughout, often coming up with ideas on how to turn his presence into a success for Mexico. He thus became our Olympic ‘Poet Laureate’ for having participated with such enthusiasm in what otherwise might have been a disaster. My father suggested giving Robert an Omega watch as a souvenir to remind him of his visit. Robert was thrilled with his gift. He referred to it in many of his letters, recalling the intensity of the moment and saying the watch would remind him of us whenever he looked at the time. For example, on November 15, 1968, he wrote: ‘Congratulate your father from me on his TIMING – the biggest triumph of the games technically at least [...] I am an Omega man now’.

He thanked me for making his stay in Mexico exciting (although I hesitate to take sole credit – or blame – for the excitement). He wished there could be a follow-up visit. He also discovered that he ‘loved’ me. Many letters repeat that he ‘loves me still’. I suppose this was a figure of speech, but he was very insistent on it and in one of his letters clarifies that amor vincit omnia can also mean ‘love binds’. He made me part of his world and probably idealized a relationship that had become personal because of the intense turn of events.

He wanted to keep an ongoing dialogue with his Mexican friends. Maybe this explains why he developed the habit of writing short letters in which he kept me abreast of his daily activities, accomplishments, trips and ailments, as well as his relationship with Julie.

The Materialist

Shortly after his return to Spain, Robert let me know that he was sent a ‘splendid’ letter from Pedro Ramirez Vázquez presenting him with a medal from the Olympic Cultural Committee in appreciation of his participation. He was happy to receive the medal, but he made fun of it because it was not real gold. He was happier when he received a letter from the Queen of England awarding him a real gold medal for his contribution to poetry in the English language. He wrote several times about medals and one saying he would have it appraised. 21 October 1968:

My [Mexican] gold medal has been goggled at by all the natives except a knowing fisherman who said: ‘those are on sale at the banks – how much did you pay in Mexico? – they are very expensive here’.

I have been offered the Queen’s Medal for my book of poems. Don’t know if I should accept. It’s given mostly to young poets with friends at Court. But I am loyal to the Crown.

Robert tended to repeat himself in his letters. This was undoubtedly due mainly to aging, however, I believe that it was also his way of insisting on facts that mattered and keeping memories alive. The scribbled scraps of paper he used to hand me during the Olympics anticipated the form of his letters. He thus went from one topic to the next in order. He often worried he had already discussed a subject. I would find jotted on the margin of the page: ‘didn’t I tell you this already in my last letter?’

London: The Art of Being Peripatetic

I wrote to him in the summer of 1970 when I was planning a trip to London and asked if he would be around. I received an immediate answer: ‘So glad you have surfaced again! Yes, I’ll be there!’

He invited me to his temporary home in the city so that I could meet his family. I was introduced to his wife, Beryl, and to a few other relatives. He then suggested we take a walk along the Thames to catch up. It was his turn to be the guide!

I had already discovered his disposition for walking during his stay in Mexico. His thoughts came faster when he was on the move. I followed his brisk steps as I had done before, while he recalled episodes during the Olympics and heard about my new endeavours. He wanted most to tell me about the discoveries he had been making in the world of mythology with reference to plants and mushrooms.

He spoke at length about the double birth of Dionysius. Robert was immersed in the study of the role of mushrooms and plants in Greek mythology. Dionysius was a mushroom commonly used in pagan rituals and was known for its psychedelic properties with its use restricted to select sacred ceremonies. Dionysius appeared in the fall at the foot of ash trees at the height of the rainy season. Robert deduced that the mushroom’s birth was associated with lightning, common in autumn storms. The ash tree attracts lightning and many pagan ceremonies, known as mysteries, took place in Athens in the fall. In the spring, there were other festivals corresponding to the flowering season. The pollen from the flowers of springtime could produce similar effects. Graves was excited to explain his discoveries in detail.

Robert’s fascination with plants sprang from his belief that the role of the scholar was to study the myths at the heart of every religion. Each myth had a hidden symbolism, and each symbol had some connection to the flora used in the production of potions, e.g. ambrosia, taken during pagan religious ceremonies. The careful study of plants would unveil the ingredients that were combined in these concoctions. Only a few individuals could acquire a deep knowledge of those ingredients. Mushrooms and potions were reserved for them and among the Greeks only the priests could ingest magical brews because of their unique connection to the gods. Mere mortals were prohibited from trying any of these mixtures. By combining the Greek initial letters of ingredients for ambrosia he concluded that they spelled the words for mushroom.

Robert insisted that all religions were based on similar rites, except for Judaism and Christianity. He told me that he had written an article on the role of mushrooms in religion for an article in The Atlantic in 1957.

Robert wanted to experiment with mushrooms himself and felt authorized to do so as a poet. He had already revealed his desire in Mexico when we first met because he had heard of a mushroom in Oaxaca that had the same properties as Dionysius. He was convinced both species could get him to the gates of paradise, and he wanted to pass through during his lifetime, especially since his health was deteriorating and entering that unknown dimension was vital for him.

We were back at square one. I had distracted Robert in Mexico with worldlier matters. But since then, he had been tormented by strange visions of faraway places. My presence and our long walk in London allowed him to talk about this. He felt free and relieved to articulate his concerns. We kept a quick pace. He was happy to share his bizarre awakenings and required no reaction from me. He was totally absorbed in his train of thought and became quite agitated with his disclosures. He lived within a world of his own that was seldom fully revealed to others.

We came to a halt at Battersea Park where he wanted to show me a bronze sculpture of himself as a fusilier in World War I. At that point he changed topics and started to talk about more personal issues. He turned the conversation to his current muse, Julie, the ballet dancer with the Danish Royal Ballet.

He explained that it was Julie who had discovered the magical relationship that bound them together. He was convinced that in questions of the heart, it was always the woman who had to reveal her feelings first because she was bequeathed with a hidden role. She was The White Goddess’s messenger who was put in the poet’s path as an incarnation of love. The poet had to cherish her. His verses would come as a natural response to her love.

Julie filled Robert’s imagination. She provided the bridge between myth and reality. He was convinced that he played the role of a soldier whose duty was to wholeheartedly serve the muse while the magic persisted.

He had encountered other muses before, but with the passage of time had eventually felt betrayed by them. He despised their unfaithfulness and their lack of total commitment. Even with Laura Riding, the woman who had had the most influence in his young life, love had come to an end. Deep disappointment and suffering had followed, and he was forced to set her aside. He remained loyal to his former muses, showing them generosity, but they were no longer his source of inspiration. They had fulfilled their role; their virtues were lost, and the poet had to carry on.

Past muses had caused him emotional damage and huge distress. He had overcome the pain as part of what he believed were trials posed by The White Goddess. However, having experienced sorrow, he now sought happier times. He was old and intuited the presence of a younger figure as a symbol of purity and virginity. Julie provided the perfect configuration to his fixation.

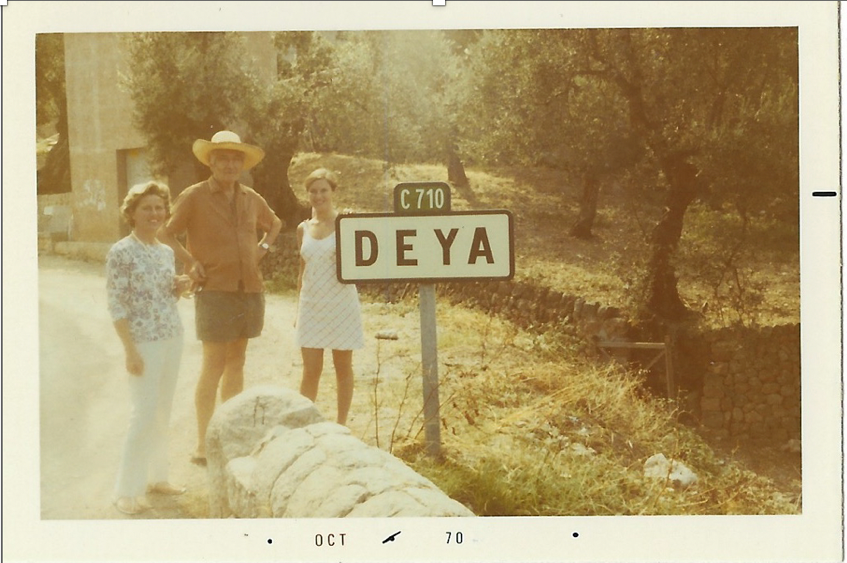

Two years later, I visited Robert in Deyá, with my parents, and Robert insisted we all come for dinner to his house on top of the cliffs. He lived in rustic surroundings: a stone structure adjoining a huge orchard. He grew crab apples and proudly told us that he picked and cooked them himself, turning them into a delicious jam in his spare time. He led us to the well in the garden and sprinkled our heads with its fresh water, making us partake of the magic of the spot. The view down to the sea was breath-taking: sharp rocks, a small bay at the bottom and the deep blue sea. There was nothing to obstruct the beauty of that fabulous place.

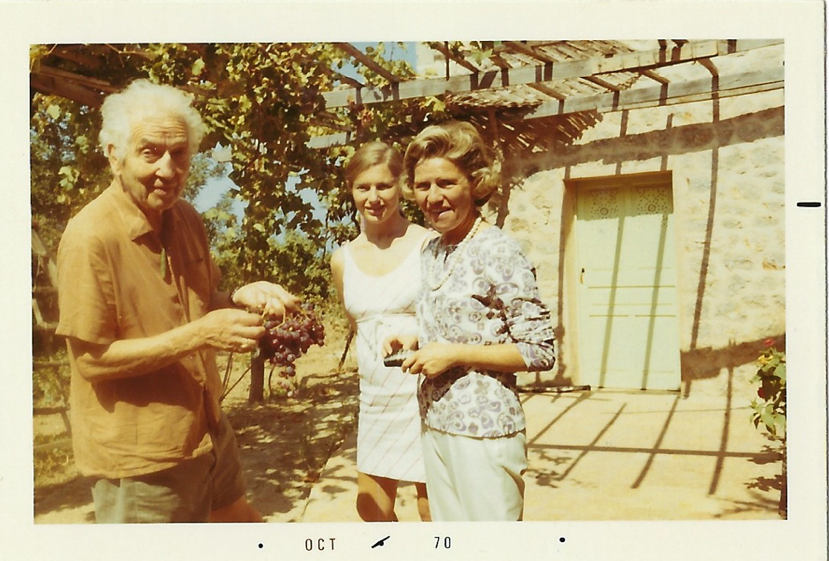

From left to right, author’s mother, Robert Graves, author

‘Omega Man!’

From left to right, Robert Graves, author, author’s mother

Beryl called us to join her for supper, greeting us with a spread of homemade food: cheese, bread and glasses of wine. This was their daily domestic ritual. After dinner, Robert asked me to take a walk with him to the village. We left Beryl and my parents behind and took an earth-beaten path that provided a short-cut leading to town. On the way, he stopped at the door of a beautiful, whitewashed house, took a key out of his pocket, opened the door with a smile and explained that we were entering his muse´s house, Julie’s abode when she was in Deyá.

In contrast to the plain stone structure where we had our dinner, Robert was excited to show off a corner with treasures he brought back from his travels abroad as presents for his muse. This was his castle, and he was the knight showering gifts on his dame. He told me Julie had this secret place a short distance from his home, where she could stay when she came to Deyá.

He proceeded to explain the origin of the objects, many of which had already been mentioned in his letters: special coins, amulets, boxes and stones. He dwelt on their provenance and symbolism, enthralled with his descriptions, and picking up the items with care so that I could closely observe them. I appreciated his enthusiasm. Each article acquired a new meaning through his interpretations.

April 9th, 1969

have [sic] just been given an oval stone found under the Roman site of Seguntium (later Sinadon, hence ‘Snowdon’, now Carnarvon) dated 200 A.D. and inscribed in Arabic characters with a prophesy that it will be worn by a poet who will discover the secret of the Welsh Hills!! So it was sent out to me (I’m having it mounted in a gold ring) Isn’t life wonderful?

In addition to the ring there also was the Mexican Olympic medal, the Queen’s medal and sundry other paraphernalia. The accumulation of objects gave a concrete presence to what until now had been merely anecdotal details. He was a historian who kept chronological records of his possessions. Everything was meticulously organized and carefully placed. He supported his stories with memorabilia. The traveling cavalier was proud to prove that his adventures were not a product of his imagination. He sought truth in his writing and these material objects were for him unrelenting evidence that his stories were based on reality. I was captivated by Robert’s complex explanations, and he was delighted with my interest. I admired his knowledge and command of names and places. He mixed personal and philosophical questions in his discourse. I had really become a friend.

My Other Agenda

Robert and I continued meeting from time to time until the end of his life. Once, after one of his poetry readings at The Mermaid Theatre in London, I introduced him to my then American banker boyfriend. Although he didn’t disapprove, he wasn’t enthusiastic because he didn’t like bankers. A few months later I sent him a long letter explaining that I had met a young and handsome diplomat in Mexico City, with whom I had a brief three-month relationship, after which we married. His response was immediate and very spontaneous:

May 14, 1971

That sounds all right – more natural and a good mixture of races and no damned technology in the air. Congratulations. Really, I´m delighted [...] Well, that´s a relief! As my mother would have said: ‘Yes, my dear, a very suitable marriage.’ [...] Hand clasp and abrazos to A. I diagnose music and a good hand at poker.

In 1974, when we were living in London and Andrés was at the Mexican Embassy, Robert came to our house for tea with a tiny dress as a present for our first daughter, born a week earlier.

I saw him several times after that. He complained about losing his memory and forgetting many of his friends. He could no longer remember his mythological heroes by name and that distressed him, but he never forgot his closest friends.

Here is the Spanish poem and English translation Robert read at the Olympic Games. As he explained it, he was singing an ode to a woman, and this woman was the human representation of the female sex who, like The White Goddess, was about to give the spark of life to the Olympics.

Antorcha y Corona, 1968

Píndaro no soy, sino caballero

De San Patricio; y nuestro santo

Siglos atrás se hizo mejicano.

Todos aquí alaban las mujeres

Y con razón, como divinos seres –

Por eso entrará en mis deberes

A vuestra Olimpiada mejicana

El origen explicar de la corona:

En su principio fue femenina….

Antes que Hércules con paso largo

Metros midiera para el estadio

Miles de esfuerzos así alentado –

Ya antes, digo, allí existía

Otra carrera mas apasionada

La cual presidia la Diosa Hera.

La virgen que, a su fraternidad

Supero con máxima velocidad

Ganaba el premio de la santidad:

La corona de olivo…. Me perdonará

El respetable, si de Atalanta

Sueño, la corredora engañada

Con tres manzanas, pero de oro fino….

Y si los mitos griegos hoy resumo

Es que parecen de acuerdo pleno,

A la inventora primeval del juego,

A la Santa Madre, más honores dando

Que no a su portero deportivo

En tres cientas trece Olimpiadas

Este nego la entrada a las damas

Amenazandolas, ai, con espadas!

Aquí, por fin, brindemos por la linda

Enriqueta de Basilio: la primera

Que nos honra con antorcha y corona.

Torch and Crown, 1968

No Pindar, I, but a poor gentleman

Of Irish race. Patrick, our learned saint,

Centuries past made himself Mexican.

All true-bred Mexicans idolize women

And with sound reason, as divine beings,

I therefore owe it you as my clear duty

At your Olympics, here in Mexico,

To explain the origin of the olive crown:

In the Golden Age women alone could wear it.

Long before Hercules with his huge stride

Paced out the circuit of a stadium,

Provoking men to incalculable efforts,

Long, long before, in Argos, had been run

Even more passionately, a girls’ foot race

Under the watchful eye of Mother Hera.

The inspired runner who outstripped all rivals

Of her sorority and finished first

Bore off that coveted and holy prize –

The olive crown. Ladies and gentlemen,

Forgive me if I brood on Atalanta,

A champion quarter-miler tricked one day

By three gold apples tumbled on her track;

And if I plague you with these ancient myths

That is because none of them disagrees

In paying higher honours to the foundress

Of all competitive sport – the Holy Mother–

Than to her sportive janitor, Hercules.

Three hundred and thirteen Olympic Games

Hercules held, though warning off all ladies,

Even as audience, with the naked sword!

So homage to Enriqueta de Basilio

Of Mexico, the first girl who has ever

Honoured these Games with torch and olive crown! (pp. 36-7)

_ _

Heartfelt thanks to William Graves and Philip Graves for transcription assistance and to William and the Robert Graves Trust for their kind permission to reprint the poems, letters and manuscript of corrected biographical introduction.

Vivian Holzer Rozental came to Mexico at the age of two and has lived there ever since. She earned university degrees at Bryn Mawr College and Columbia University. After her studies in the US, Vivian worked in the cultural department of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and as an editor for various publications. She is married to a career Mexican Ambassador and has lived in the UK, Switzerland and Sweden. They have two daughters and four grandchildren.

NOTES

It was a Great Games; and as I prophesy the last probably for a few decades. Munich will be a shambles, even if there is a Games there. The Germans have no cariño, no fuego, no duende no … etc.

The reality would prove to be even more terrible than he predicted.