|

Search Help |

|

Links Robert Graves Website Other RG Resources |

Critical Studies

Poet in the Nursery

One goes plodding on and hoping for a miracle, but who has ever recovered the strange quality that makes the early work (which follows a preliminary period of imitation) in a sense the best work? There is a fine single-heartedness, an economy of material, an adventurous delight in expression, a beginner’s luck for which I suppose honest hard work and mature observation can in time substitute certain other qualities, but poetry is never the same again.

Let’s start with a joke: a student approached Jean Paul Sartre one day and said, ‘Maestro, I am seriously contemplating suicide’, to which Sartre is believed to have replied, ‘of course!’ Stanley Fish, who is to creative hermeneutics what Sartre was to suicide, might have said ‘of course’ to Peter Howarth’s observation: ‘Robert Graves makes it impossible for the reader to distinguish quite what belongs to the poem and what to her.’

‘Allie’

I’ll begin by framing my analysis with reference to another early-ish and better-known poem, ‘Allie’, written in 1920. ‘Allie’ is a wistful, mysterious evocation of bucolic childhood, as well as, without seeming to be, a polemic against warfare and the culpability of innocence – a veiled criticism of adult innocence as merely the outward trappings of a stunted conscience.

‘I’ve discovered a brilliant young poet called Sorley whose poems have just appeared in the Cambridge Press […] & who was killed near Loos on Oct. 13th as a temporary captain in the 7th Suffolk R. [Regiment]’

It seems ridiculous to fall in love with a dead man as I have found myself doing but he seems to have been one so entirely after my own heart in his loves and hates.

Graves would not stick to Sorley’s valediction forbidding mourning, as we see in ‘Haunted’, a poem published in Country Sentiment (but later removed from the canon). However, he both mourns and suppresses mourning in ‘Allie’.

But one might turn ‘Allie’ ninety degrees and see in it a clash of conflicting views of England, a double-vision that anticipates Graves’s self-exile:

‘The Gnat’ and ‘Gnatiness’

Often the conflicts that surface in Graves’s poems have been ascribed to post traumatic stress disorder.

Graves explains, ‘”The Gnat” is an assertion that to be rid of the gnat (shell-shock) means killing the sheep-dog (poetry).’

Reading between the lines, we see Graves recalibrating his allegory; now that the gnat may be read as a symbol of the illogical, we can easily see the shepherd as the reader struggling to fully understand what cannot be understood, and the sheepdog, the poem ‘as a poem’. Dispatch the illogical and you lose the poem. Dispatch the gnat and you lose ‘The Gnat’. If we adhere to Graves’s interpretation, we must examine its inconsistencies, or rather its consistent inconsistencies.

Actual shellshock (to use Graves’s word) is real and persistent in Graves’s life and work. But if we forbear from assigning it full explanatory power – which is to say resist the temptation of turning it into myth – it emerges as an ambiguous signifier that serves as a comprehensible, stabilizing evocation of an indefinable psychological structure that survives in Graves from childhood and is indeed an integral part of him: Graves, the poet: Graves as Graves.

If we persist in seeking biographical traces of the poetic, we can catch glimpses of pre-war ‘gnatiness’ in Graves’s famous account of childhood in On English Poetry (1922). His description of ‘amazed wondering, sudden terrors, laughter to signify mere joy, frequent tears and similar manifestations of uncontrolled emotion’ seems to mirror his own behaviour.

‘A sweat of terror’ and ‘overcome with horror’ echo phrases in Good-bye to All That describing the hypersensitive responses of a neurasthenic soldier. Jean Moorhouse Wilson sympathetically recounts the abuse the adolescent Robert van Ranke Graves endured at the hands of his Charterhouse classmates who resented both his oddness and German middle name, and provides a plangent example of Graves linking poetry with madness:

Whether his ‘heart went wrong’ as a result, for physical or

psychological reasons, is impossible to say, but he was forbidden to play football for a time. His most extreme measure was to ‘sham insanity’, which succeeded unexpectedly well, especially after his first poem appeared in the school magazine, The Carthusian: ‘This was considered stronger proof of insanity than the formal straws I wore in my hair.’

In these anecdotes, Graves’s high-strung, temperamental behaviour seems consistent with his post-War behaviour, such as leaping up at the sound of cars backfiring or at the ring of the telephone. Of course, these latter responses were conditioned by or induced by shellshock: but not determined by it. What we see in the post-war, shell-shocked Graves had its roots in a condition implicated in a mode of consciousness that Graves associated (I will say of his own free will, though he would later ascribe agency to the impersonal force he called The White Goddess) with poetry.

After the war, Graves may have identified shell-shock with the gnat of poetic inspiration, but clearly the mode of consciousness capable of containing anything as extravagant as the gnat, or apprehending it as the sacred (or, to phrase it somewhat differently as something that cannot be reduced to the symbolic order of experience), epitomized that which Graves felt inspired to protect from the rational and hence reductive, ‘cure’ of the psychoanalyst. In this perspective, war-trauma is itself a reductive, desacralizing, term, crucially at odds with poetry.

‘Who Did That’

In 1902, at age seven, Graves asked his mother Amy (Amalie von Ranke), if she could ‘leave him money in her will: not for any selfish purpose, but so that he could buy a bicycle and ride upon it to her grave’.

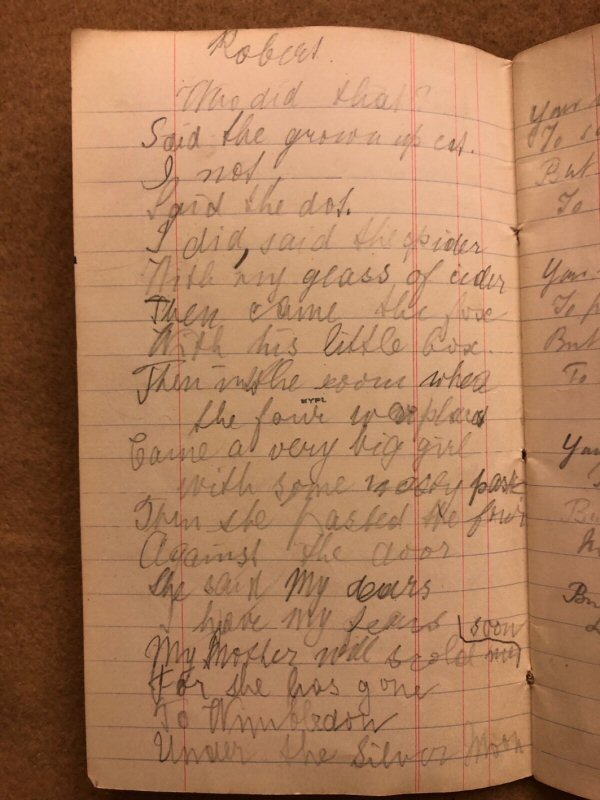

I have transcribed the poem, keeping the indents as written but justifying the left margin as I believe was intended. I’ve also preserved the punctuation, or relative lack thereof.

Who did that?

Said the grown up cat.

I not

Said the dot.

I did, said the spider

With my glass of cider

Then came the fox

With his little box.

Then into the room where

The four were placed

Came a very big girl

With some nasty paste

Then she pasted the four

Against the door

She said My dears

I have my fears

My mother will scold me soon

For she has gone

To Wimbledon

Under the Silver Moon

To begin with the most obvious of observations, Graves wrote his first poem while ill or recovering from illness, thus anticipating the connection he would draw later between illness (shellshock) and poetry.

One can also find affinities between ‘Who Did That’ and Graves’s studies of poetic form and mythology. If I over-perform the text, as Fish, and perhaps as the older Graves, imply we cannot help doing, even up to the point of committing a kind of hermeneutic suicide, I might suggest Roberty anticipates Graves’s intuitive apprehension of the ‘Cutty Wren’ theory, which posits a pagan survival in ‘Cock Robin’, recollecting the ritual sacrifice of the king.

Reading ‘Who Did That’ more safely as the first of Graves’s many dream poems, we can see it drawing power as a poem from the awakening poet’s precocious simulation of how the dreaming mind shifts through transpositions of reality. The poem starts with an accusation and introduces four cartoon-like characters. The first of these is the cat making the accusation (or the author who becomes the cat by his attribution); the following three respond with contrasting defences. The first respondent is the jot above the lower-case I, whose denial ‘I not’ connotes self-denial, if we take the ‘I’ to refer back to the speaker (perhaps the poet who has slipped into the role of the cat, and is, indeed, no longer Roberty). The transformed glyph illustrates that Roberty has an intuitive grasp of how poetry’s elasticity can mimic the elasticity of dreams, and marks the first appearance of the grotesque element we encounter again in ‘The Gnat’. After ‘I not’, follow the spider’s facetious confession and the fox’s suspiciously tardy arrival.

This introductory, dialogic, phase of the poem terminates with the sudden appearance of a fifth character, a girl characterized as ‘very big’. Her arrival culminates in a violent act of pasting, and the simultaneous contraction of the individual entities to ‘the four’, which reveals that cat, jot, fox and spider are not conscious characters within the landscape of the poem, as they are first presented to us, but drawings, or marks on paper: symbols mediated by other symbols on paper, the poem. As such they remind us of the epistemological problems readers will ponder in later poems.

With the ‘very big girl’s’ appearance, the centre of consciousness also contracts to that of a single self, though one whose affect is unstable, turning from brash and bold to fearful. After dispatching the four, she fears that she will be reprimanded, whether for some undefined transgression that can either be assigned to the act of pasting, to the nasty paste she’s smeared on the door, to something else, a thing that cannot be named, or to nothing, no reason: the irrational.

Then the poem undergoes another transition as the very big girl contemplates the fairy-tale-like disappearance of her mother (an exit balancing her entrance as well as the contraction of the characters in ‘the four’) which leads to the fourth and final segue that introduces the ‘Silver Moon’, an image that, as remarked by RP Graves, derives from the first poem in The Song Book, Amy’s ‘The Lost Child’. With an eerie ambiguity, the moon, the object of the very big girl’s gaze, seems almost to jutter toward subjecthood, recapitulating the opening theme of an inanimate entity capable of consciousness, and suggesting an act of inanimate or transhuman scale-balancing. Altogether, the direction the narrative takes is unpredictable yet decisive, lively, multivalent, and strangely logical: dreamlike.

Before solving the central mystery of the poem, ‘who did that?’ (and what ‘that’ is), I want to look at the confident formal control of the not-yet four year old poet and demonstrate that the poem’s structural complexity expresses the conflicted, ambiguous components of the self that will inform the shell-shocked Graves, and his progressively older, and less clumsy, selves.

While most four-year olds can repeat their dreams, and some can express them in meter and rhyme, Roberty uses meter and rhyme to shape and articulate the dream’s latent content: he gives the dream content poetic form and expressive power. Consider his treatment of the poem’s first crisis, the sudden manifestation of the very big girl on lines nine through twelve, in a passage that diverges from the tone and focus of preceding lines.

Then into the room where 9

The four were placed

Came a very big girl

With some nasty paste.

The eight lines before this quatrain are end-stopped. In contrast, line nine is a catalectic line seemingly splitting a metrical foot completed on line ten. (Pressed by the rhythm, the reader wants to make the two lines one, a temptation to which RP Graves yields in his transcription.)

Page from Red Branch Songbook (The Henry W. and Albert A. Berg Collection of English and American Literature, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations)

The text is clearly written out in pencil, so if he thought he’d made a mistake, he could easily have corrected it, or had it corrected, and line ten is amply indented, allowing room for another word at its head.

We find the crisis impressed firmly into the rhyme scheme. The pattern established in the initial octet of uniformly end-rhymed couplets concludes with line eight. Line ten, ‘The four were placed’ (F1, where we would expect to find E2), violates the pattern by not rhyming with ‘where’, line nine. ‘Placed’ not only does not rhyme with ‘where’, it emphatically does not. The phonological difference between the sibilant ‘placed’ with its unvoiced dental t, and the r-controlled air sound ‘where’ calls attention to the absent rhyme, just as the indent calls attention to the idea of alteration or modulation. And, of course, both call our attention to the idea of something missing or indefinable: the mystery at the heart of the poem. The formal disruptions in layout, the pattern of end-stopped lines and rhyming couplets serve as an overture to the very big girl’s big entrance on line eleven, and the havoc she creates. With this stanza, Roberty breaks decisively with his model; he is no longer copying ‘Who Killed Cock Robin’, and is in fact heading toward John Skelton, and beyond.

Line eleven, ‘came a very big girl’, is a remarkably unchildish line, piling anomaly on top of anomaly: 1) the size of the new character is disproportionate; 2) the new character is human, not anthropomorphic; 3) and she is gendered; 4) the word ‘girl’ at the end of the line does not rhyme with either ‘where’ or ‘placed’, and thus it additionally warps the poem’s couplet pattern; 5) it inverts the usual order of parts of speech: ‘came a very big girl’, an anastrophe emphasizing the extraordinary liminality and illogic (or dream logic, the insistent parenthetical) of the passage, and amplifying the anxiety felt by ‘the four’ (provoked either by being interrogated or by the girl’s size, gender, species, or uncertain, volatile, disposition, or perhaps by a kind of transcendent awareness of their terminal insubstantiality); 6) the line disrupts the cadence of the poem. Up until now, Roberty has allowed two pulses to each line:

Who [. . .] that?

[. . .] grown [. . .] cat.

I not

Said [. . .] dot

I [. . .] spi

[. . .] glass [. . .] ci [. . .]

Then [. . .] fox

Lit [. . .] box

[. . .] in [. . .] room [. . .]

[. . .] four [. . .] placed

With the additional emphasis on ve-ry on line eleven, calling attention to and reinforcing the novelty of the phenomenon by introducing the poem’s only adverb, Roberty communicates the unprecedented size and three-dimensionality of this new creature and perhaps the shock felt in her presence by ‘the four’; the adverb also insists that this extraordinary event has ontological weight: it is a very big deal: it matters in a way ‘the four’ do not, that the girl has girth, that she inhabits three dimensions, not two: materiality matters – the materiality of the poem; therefore, by association, that the crisis in rhyme has spread to meter matters.

With the manifestation of the girl, the four characters congeal into one gluey mess. Their independent identities cease to be – indeed, illogically, they cease ever to have been, and we now see them, not as they seem to have been to themselves, an sich, but as they might appear to ordinary human eyes, just as we see her as they seem to: large and in charge, overbearing and grotesque: a precursor of the intolerable gnat. Perhaps we even see the four as they now see themselves through her eyes as things to be organized or disorganized: just as the card people at the end of Alice in Wonderland might have seen themselves through Alice’s eyes.

Carter observes that ‘childhood is a constantly recurring feature of Graves’s verse’.

‘Childhood’ is a mental construct through which we first experience the sacred (by which after Eliade I mean order, coherence, meaning, the real), and so the mind never fully relinquishes it, just as the gnat never goes away. By subjecting his dream to the rigor of poetic structure, Roberty is able to transcend the particular and the trivial and impart in poetic form an observation about the nature of experience mediated by childhood.

But, just as the older Graves, at age twenty-nine, writing The Meaning of Dreams, deems the gnat indispensable to his poetry, so, too, is the very big girl indispensable to the fabric of the poem she seemingly vitiates. Her actions on line ten disrupt the rhyme scheme, but then repair it on line twelve, with the word ‘paste’, rhyming ‘placed’, completing the unbounded or ballad quatrain: ABCB. Thus, Roberty makes the act of destruction simultaneously the act of creation, which ‘paste’ cleverly points out (reattaching bits of the broken rhyme scheme as one might reattach torn scraps of paper or scrapped verse). Just as this agent of chaos seems to be demolishing the poetic structure, she rebuilds it, or it rebuilds itself through her, by recycling chaos as a metamorphic structural element. The affirmation travels up the chain of signifiers: Incoherence becomes an aspect of coherence, and inconvenient poetic insight completes a schema in which it matters. Poetic insight arrogates to itself ontological weight.

Having sealed the breach of EFG, Where | Placed | Girl, and then re-absorbed the anthropomorphic qualities the marks on paper had borrowed back into the human, the poem then returns to its rhymed couplets, but with a difference:

Then she pasted the four 13

Against the door

She said My dears

I have my fears

Although lines thirteen through sixteen seem to reprise the motif of rhymed couplets (line thirteen even repeats the same word as line seven, establishing a lexical identification beyond metamorphosis), in fact it diverges from what we might call rudimentary or perhaps immature motif in an ingenious and problematic way. In addition to the pair of perfect rhymes AABB (or HH/II), four/door and dears/fears, the lines contain a pair of imperfect rhymes: four/fears; door/dears (HI/IH, or H1/I2; H2/I1). Weaving together perfect and imperfect rhymes, Roberty accomplishes yet another technical feat, which he once again models as a structural metaphor. The four end rhymes appear either to be converging into one indistinct monorhyme, in mimicry of the implosion of ‘the four’, or else, conversely, struggling out of the one, a lost morphological etymon comprising ‘four, door, fear, dear’, to become four, signifying the creative gesture, and more immediately, the creation of this (first) poem. And that lost notional wholeness that creation requires phonologically plays into the poem’s theme of loss, conveyed explicitly by the lost mother and the loss of agency exemplified by the cat, the fox, the spider and the I-less jot.

We can stretch probability a bit further and view the tensions in this pair of couplets (particularly the tension between the perfect and imperfect rhymes) as a struggle between dominant and subordinate personalities, an opposition that harkens back, once again, to ‘The Cutty Wren’. Here I want to point, in passing, to the obvious affinities between this binary and the vision of royal succession, the storied combat between the oak and ivy kings, under the spell of The White Goddess, which, the older and wiser Graves (age fifty-two: Graves as Graves) will propound as the original monomyth for the tale of ‘cock robin’.

We call the subcategory of imperfect rhyme superimposed on this pair of couplets pararhyme (also, rim rhyme or alliterative assonance), and define it as a rhyme containing a vowel variation within the same consonant pattern. The Wikipedia illustrates the form in another intriguing coincidence with a Welsh cynghanedd written by none other than Captain Graves during the War, but first published in The White Goddess.

Billet spied,

Bolt sped.

Across field

Crows fled,

Aloft, wounded,

Left one dead.

The tensions between the perfect and imperfect rhymes (pararhymes) present as well in ‘Who Did That’. In ‘Billet spied’, the pararhymes form couplets, while alternating lines bring together other rhymes: a third pararhyme in lines one/three, and a perfect rhyme in lines two/four, sustained over line five and repeated on line six. The rhyme’s repetition (‘dead’, ‘fled’, ‘sped’) denies the resolution of the initial long vowel (‘spied’), performing in the rhyme’s timbral dimensions the struggle between safety desired and denied. In the earlier, ‘Who Did That’, Roberty superimposes the pararhyme on the rhyme to perform the very big girl’s anxiety (it would appear). He sustains the counterpoint, if not the pararhyme, in the following lines, seventeen through twenty, which conclude the poem:

My mother will scold me soon 17

For she has gone

To Wimbledon

Under the Silver Moon

Here the rhyme has migrated to the 2nd and 3rd, and 1st and 4th positions (lines eighteen/nineteen, and seventeen/twenty). The sense of safety or closure the enclosing rhyme (soon/Moon) might have afforded readers is disturbed by the vowel dissonance in the couplet positions: positions 1/2 and 3/4 (lines seventeen/eighteen, and nineteen/twenty).

On line eighteen we expect a rhyme to ‘soon’ (line seventeen). On the model of lines thirteen to sixteen, HH and II, we expect J2 (i.e. June, moon, croon). But instead we get ‘gone’, following J1 with K1. We logically read ‘gone’ as a formal stumble, a garden path rhyme. But J2 (‘Wimbledon’) followed by K2 (‘Moon’) assures us that the swerve to K1 (instead of J2) was a sure step within a deliberately improvised pattern, JKKJ, an enclosed-rhyme quatrain, again with a distinct pay-off. By rhyming the enclosing 1/4 lines (JJ), and the enclosed 2/3 (KK), the quatrain echoes the imperfect rhymes in the proceeding pair of couplets (four/fears; door/dears); and with its own imperfect rhyme (gone/Wimbledon), it once again foregrounds and reinforces a sense of uneasiness and mercurial self-awareness conveyed by the preceding pararhymes.

I find the musical dissonance in the slight phonological slip between ‘Wimbledon’ and ‘gone’ utterly beautiful. The missed match combined with the drawn-out vowel in ‘gone’ suggests an anxiety-induced slip of the pen, a slight lapse of self-control from which the poet will nimbly recover to make the final rhyme soon and moon perfect: yet, almost too perfect to be quite reassuring. Despite being in a subordinate, interior, position, the imperfect rhyme lingers, scraping against the smooth veneer of the perfect. Again, there is a palpable benefit to these technical moves. By overwriting the imperfect rhymes on thirteen and sixteen (four/fears) with perfect (soon/Moon), the stanza joins the combat between dominant and subordinate personalities, transmuting the very big girl’s emerging anxiety, and transmitting it to the reader.

My mother will scold me soon Then she pasted the four

For she has gone Against the door

To Wimbledon She said my dears

Under the Silver Moon I have my fears

The symmetrical meter locks the rhyming lines in place while boldly displaying their duality

My mother will scold me soon 17

For she has gone

To Wimbledon

Under the Silver Moon.

The two ‘A’ lines (seventeen/twenty) replay the heavy three-beat measure, a variation introduced into the poem in the anastrophic line eleven, ‘Came a very big girl’, while the lighter two ‘B’ lines (eighteen/nineteen) continue to sound the signature measure of the poem, a two-beat measure. The weaker dimeter lines recede but never disappear, while the poem’s final line, the dancing trimester (‘My mother will scold me soon | Under the Silver Moon’) plays a ghostly solo in the penumbra of the poem after the text recedes. The triple cadences seem to continue to fall through which we may imagine we hear the dissonant gone/Wimbledon, as almost a muffled chant.

Analysing repetition in music, Elizabeth Hellmuth Margulis describes how group chanting followed by silence can set up a physical experience of ‘singing that never ends’, or a musical figure that moves ‘from the sounding, external world of the co-participating community’ into ‘the interior, subjective, felt world of the individual’.

This connection that can exist between sounding music in the external world and imagined music in the internal one has been hypothesized to set up the conditions whereby a person can experience a highly pleasurable sense of extended subjectivity, or a perceived merging with the music.

Roberty’s triple cadences create a comparable sense of merging that tweaks the boundaries between reader and poetic music with an exquisite effect we have learned to recognize and admire in his mature work. In ‘Counting the Beats’, for example, the repetition of ‘you and I’ promises the beloved addressed in the poem a transcendent continuity (which the repeating figure of the amphimacer performs metrically).

If we step back from our analysis of the line, we see that lines seventeen through twenty form the poem’s second quatrain. Concluding the poem, they also allow readers their first glimpse of the poem’s structure in its entirety. It becomes possible to consider that Roberty intended the first quatrain, which initially seemed structurally wayward, to introduce a binary pattern, in which it does double duty: both as a transformation and restatement of the rhymes and meter producing the initial couplets, and as the initial quatrain of a dyad, thus a symbolic assertion of the poem’s split personality. At this point we may even infer the presence of a third crisis in the asymmetry of the poem: four couplets | a quatrain | two couplets | a quatrain. The final quatrain speaks over the two additional couplets that would give the poem perfect structural symmetry. The disappearing couplets suggest the disappearance of the girl’s mother as they trace the movement of the poem’s centre of consciousness from dream to uneasy waking.

In Effects of Musical Expertise and Boundary Markers on Phrase Perceptions in Music, Neuhaus, Knösche & Friederici found that people listening to music tend to view pieces with an AABB (couplet) structure as sequential, and an ABAB (stanza) structure hierarchical, and possessing greater coherence.

We can spot the counter-self emerging again in the mutable identity of the penultimate passage, lines thirteen through sixteen. On their own, they appear to be two intermediate couplets. But, bracketed by non-identical hierarchical quatrains, they acquire the hybrid identity of a quatrain with sequential rhymes, a heroic stanza: thus these four lines can be defined as a pair of couplets, as a quatrain, or as a provisional quatrain: a quatrain with an unstable, dissonant, identity (neither innocent nor sophisticated).

No less astonishing than his proficiency with meter and rhyme is the toddler poet’s skill in gaining our sympathy for the monstrous girl, in spite of the blood, figuratively speaking, on her hands, which, once again, reveals enigmatic tensions and polarities that inform the shell-shocked Graves, and suggest an innate ‘gnatiness’. The very big girl’s mother has probably left her an orphan (there’s no father in the picture), and she fears dreadful punishment.

With the introduction of the moon, the poem completes its sketch of the ladder of being (the scala natura): drawings of small creatures on paper at the bottom, small animals above them, then humanity comprising children, and mothers, then the uppercased ‘Silver Moon’ – the celestial entity, marked both by capitals and by the poem’s one and only use of colour: just as he spent the poem’s lone adverb ‘very’ to exemplify the girl’s dominance over the four, Roberty reserves the lone colour word to highlight the moon’s dominance over all. He pointedly analogizes the very big girl and the moon. The moon’s qualities, its colour, radiance, capacity for heavenward flight, overawes the girl, just as her vast sentient humanity overawes the four. It also suggests her contradictory nature: she is both dominant and subordinate, mercurial and as capable of change as the moon, a subject possessing authorial intent, and a sign to be animated and valorised by meaning and intentionality. As a symbol of psychological domination, the moon in this early poem powerfully suggests that Roberty had a sense of his own contingency (as a sick child, youngest of three, and solitary male, might), and that weakness was inexplicably fused to unpredictable flights of fantasy.

In setting up an equation, as the very big girl is to the four, so the moon is to the girl, the poem repositions the reader’s sympathy with the weak and vulnerable, pointing out the universality of dread in the face of the mysterium tremendum. And if we categorize the jot and the other drawn characters as marks on paper, the poem seems to be inviting our admiration for the dreamlike, transpersonal power of poetry by which creatures, humans, and the supernatural are all made and fluently remade.

The patterns described above are well-known to most of Graves’s readers, though some may wonder to find them in this cornerstone text. However, everyone will spot the similarities between the final image of the Silver Moon in ‘Who Did That’ and the moon in ‘I Hate the Moon’, penned in ‘August 1915 (after a moonlight patrol near the Brickstacks)’.

I hate the Moon, though it makes most people glad,

And they giggle and talk of silvery beams–you know!

But she says the look of the Moon drives people mad,

And that’s the thing that always frightens me so.

I hate it worst when it’s cruel and round and bright,

And you can’t make out the marks on its stupid face,

Except when you shut your eyelashes, and all night

The sky looks green, and the world’s a horrible place.

I like the stars, and especially the Big Bear

And the W star, and one like a diamond ring,

But I hate the Moon and its horrible stony stare,

And I know one day it’ll do me some dreadful thing.

Notice that the voice of ‘I Hate the Moon’ is far from the hard, laconic, voice of ‘Billet spied.’ It is unsoldierly, if we take the narrator of Good-bye to All That as the standard. And the images, e.g. giggling, eyelashes, a diamond ring, are feminine by convention. Similarities between this persona and the very big girl in ‘Who Did That’ (lines fifteen-twenty) stand out. We must also admit a similarity between the setting of ‘I Hate the Moon’, with its green sky and the moon’s ‘horrible, stony stare’, and the scene of Wimbledon under a bright, scolding moon in ‘Who Did That’, as well as the very big girl’s absent mother and the mysterious ‘she’ in the later poem’s first stanza. Even if Graves hadn’t published this poem as one of three ‘Nursery Memories’, we would still recognize it now as the older sibling of ‘Who Did That’.

Kersnowski finds the presence of battle fatigue in ‘I Hate the Moon’ and speculates that Graves’s mind is bending under the stress of constant war anxiety, even regressing. I would suggest that Graves’s mind is deliberately turning toward the three-year old self who wrote ‘Who Did That’, perhaps, a dream version of it. That nursery/dream moon overlays this one, which soon after the patrol he described as ‘evil’ in a letter to his father. If Graves’s mind is bending (as is his gender) under the stress of war, that should rightly be regarded as a critical observation rather than psychoanalysis, for one sees the same bend in ‘Who Did That’, the same thrusting fear of death that metamorphoses into the image of the silent moon, the same ‘she-ness’, the same anxiety. But, why is it necessary to see Graves’s reversion to childhood here as a retreat from the anxiety of war? In On English Poetry, written twelve years after ‘I Hate the Moon’, he provides a logical pretext for adopting a childish perspective in poetry:

[D]reams are illogical as a child’s mind is illogical, and spontaneous undoctored poetry, like the dream, represents the complications of adult experience translated into thought-processes analogous to, or identical with, those of childhood.

We want to claim access to Graves’s psychology in ‘I Hate The Moon’, but we can more justifiably claim access to his technique, his linguistic play.

This I regard as a very important view, and it explains, to my satisfaction at any rate, a number of puzzling aspects of poetry, such as the greater emotional power on the average reader’s mind of simple metres and short homely words with an occasional long strange one for wonder (68).

Should we insist on deriving meaning from psychoanalysis, we must acknowledge that we are seeing in ‘I Hate the Moon’ a specifically Gravesean psyche; and, that Graves, himself, is acutely conscious of it. He knows himself as both victim and conspiring partner to the cruel intrusion of the irrational, in its myriad of forms and disguises, and I would argue this knowledge, which seems (with regard to ‘Who Did That’) almost to pre-exist experience, palliates his suffering. It provides him with a crucial catharsis (self-knowledge is both cure and disease), as it might for the reader, pencil in hand. We might extrapolate further and say

that Graves the soldier poet of ‘I Hate the Moon’ recognizes shellshock as a familiar if ever-strange entity, or rather he perceives in shellshock the impress of something he has known forever, the ‘certain intense and not to be defined quality which must disappear in translation’. Uncomfortable though it is, it is the emblem of an all-powerful, ontologically saturated world, and thus a vital safeguard against the unimaginable, the emptily profane: the translation.

That Roberty is already aware on several levels of his own divided self can be ascertained in other ways, perhaps even by his distribution of the narrative among the girl, the ‘grown up cat’ (which seems a foreshadowing of her), and himself. We also see an awareness of the divided self in the portrait of imbalance, or perhaps a contrapposto balance, advanced in the poem’s subtextual melodrama. The very big girl’s matrifocal anxiety and her apprehension of the powerful moon are highly evocative. Being full-sized, the girl seems to suggest the full moon, ‘cruel and round and bright’, and by the same token, a very large jot. Perceiving the moon as a lidless, all-seeing eye aware that she has violated a taboo, whether that be stripping the four of their singularity, mobility, agency and vitality, daubing the wall with stinky paste (a crude artistic act), or something worse, she is presented to us viewing and judging herself with cold impartiality: a ‘hard, stony stare’. Gazing at the moon gazing back at her, as though from a silvery mirror, the girl experiences (and represses) guilt. Reading the moon as a luminous hole in the black sky, the girl fears her mother will fall into it, or, she will, herself, without her mother’s protection, big and powerful as the poem deems her to be, for she has not been pasted down.

I’d like to conclude my discussion by considering the question: who did that? The line imitates or even derives from ‘Who Killed Cock Robin’, but, less obviously, it also echoes the opening line of Hamlet, ‘Who’s there?’ And the definitive ontological question, which hovers over Hamlet, what is real, is very much on the lips if not on the mind of ‘Who Did That’.

Roberty conceals the nature of the act: the ‘that’ (which ‘Who Killed Cock Robin?’ suggests is murder), as well as the identity of its perpetrator. While the jot immediately denies the accusation, and the fox belatedly enters the scene and does not appear to have heard the question (his tardiness, a brilliant dramatic foil), the spider blurts out a confession. But we are obviously meant to discount it, for it is nonsense. The murder weapon, a glass of cider, is not only incapable of doing harm, even to the drinker, but is transparently so. Perhaps Roberty even meant the rhyme to be a joke at the spider’s expense. Although the spider confirms that there was a ‘that’, a prior act that prefigures the nasty pasting the girl gives the four and the goose-bumps she will experience beneath the moon, his or her arachnoid confession is ironic; surely it is meant to be exculpatory, even perhaps burlesque, an inverse claim of innocence, in which the poem demonstrates an awareness of irony and reminds us that we should regard avowals of innocence as sceptically as confessions of guilt. Roberty may even be suggesting that the spider intended its absurd confession to amuse, or, insidiously, to inspire trust – an enticement to all prospective flies (or gnats) to come just a little bit closer.

But the question ‘who did that?’ seems to have an answer to which the poem provides clues. The conspicuously furtive fox is a suspect, though, again, not a convincing one. And, what of the mysterious box? A box might be a weapon, though more usually a coffin or a casket for ill-gotten gains (the sort of gains an ill poet might boast). The box may be construed to be incriminating evidence of yet another crime, not necessarily unrelated to the one at hand. Moreover, as a container it suggests the containing (and contained) structure of a poem or a stanza, which may shed a new and sinister light on the poem’s impromptu quatrain outbreaks. Are they also boxes of purloined goods, rhymes and images stolen from earlier poems, traditional verse or perhaps, as RP Graves suggests, one of mother’s? The infant’s bounty of adult language then may not be a symbol of mastery in the sense of achieved or even purloined sophistication, but a hasty, premature rejection of the condition of innocence.

The word ‘stanza’ derives from the Italian word meaning standing place or room; and in drawings, rooms often appear as open boxes. So, while the fox draws attention to himself, he also reflects attention back onto the poem, the box he, and, momentarily we, inhabit. Fox and spider then both suggest surrogates of the wily, protean poet.

Furthermore, what shall we think about the cat? Is s/he merely curious, or inquisitorial and bossy? Is s/he beyond suspicion? Is there nothing curious about his/her curiosity? By characterizing the cat as ‘grown up’, Roberty seems to be hinting that the anonymous perpetrator of the putative crime is not grown up. He supports the implication by using, again, a parallel construction. On line eight, he characterizes the fox as little, anticipating the appearance, three lines later, of the very big girl. Similarly, and by analogy, by characterizing the cat as ‘grown up’, he seems to be planting a clue that the perpetrator of the foul deed is a child, and thus supposedly innocent, yet still guilty. And this opposition previews the dialectic of innocence and sophistication that plays throughout the poem, while it also suggests a paradox, therefore trapping the rational mind in a box of its own ratiocination (anticipating the later ‘Warning to Children’).

Since the unnamed act is a McGuffin that brings the poem into being, the guilty party may be (this will surprise no one) the perpetrator of the poem, the curious maker of stanzas and puzzles, the youngest child or belated arrival, the soapy-fingered spinner of sticky webs, the as-yet not completely formed I, and maybe a drinker of sweet cider.

The girl would have been the artist who drew the four since it was she who mounted them for display on the wall, or secured them to structure, either to prevent precipitous transport or to enable them to survive the soap-bubble collapse of the dream.

Her guilt is simultaneously her pride of creation; and from here we can pursue or at least gaze out on the poem’s allegorical references to the fall, from whose quintessential symbol one may derive cider, and procreation.

The various threads seem to converge at the simultaneity, or coincidence, of sacred and profane. At its core, poetry is murder: creation entails destruction since it liberates the irrational which, gnat-like, wreaks havoc on the pre-existing order by abolishing the rational distinction between opposites: the gnat’s truth is ‘that profane human existence may be hell, but it is simultaneously heaven’,

And, again, a child creator presumes on the prerogatives of adults. Indeed, ‘The Poet in the Nursery’, the initial poem in the Carcanet collection of Graves’s poetry from which I have copy-pasted my title, begins precisely in that act of subversion. A poet in the nursery breaches the boundary between adult and child, thus it is a scandal: not a murder per se but symbolically so since it erases or rubs out identities. The grown-up cat in our poem may then not be asking but rhetorically admonishing the child poet, the way a parent might a child or a mischievous cat: “who did that?”; and the gang of four may not represent a police line-up so much as a host of disguises through which the child poet seeks to protest his innocence, or, simultaneously, innocently confess his guilt, while, ironically, re-enacting for his own pleasure, and that of the reader over his shoulder at Red Branch Cottage, versions of the initial offense. (Let me point out here that Graves published well over fifty books of poetry, and there are 835 pages of poems in The Complete Poems in One Volume,

Considering the identification of poet as the guilty party, we then can read both the spider’s false confession, and the jot’s denial ‘not I’ as the poet’s confession: I, Robert Graves (which is, of course, the name at the top of the poem). The conflation of innocence and guilt returns us to the idea proposed at the top of

the paper, that Graves’s sense of a divided, conflicted self predates the war and probably anticipates the forms of expression shellshock would assume.

So, let’s be careful when we ascribe explanatory power to shellshock, and look askance at anyone who interprets a poem as ‘therapeutic’; and understand shellshock is not incommensurable, and that it is only metaphorically the source of inspiration that Graves at age twenty-nine equivocally described it as being, merely a complication, or a way of thinking about the ineffable, the sacred, or what he would later call ‘poetic truth’.

Postscript

The foregoing analyses rest on the assumption that criticism is free to interpret a poem in ways that are compelling or at least amusing, and internally consistent though not necessarily comfortable with certain ‘facts’ about the poem that might be traditionally thought to direct interpretation. For example, because the name ‘Robert’ is written at the top of the page, I have interpreted the poem as if it were composed exclusively by Robert Graves, and that ‘Who Did That’ reflects poetic genius resident in a precocious child possessing the character, albeit in embryonic form, of the mature man, and that the mature man possessed the character, in mature form, of the poetic genius resident in the precocious child. But there is a ‘fact’ about the poem I have taken the liberty of ignoring, which I want to conclude by addressing: the context of its creation.

The Red Branch Song Book begins with Amy’s poem titled ‘The Lost Child’, written in couplets, and containing a ‘silver moon’ as well as a giant – a forerunner of the gnat, perhaps – who beats the lost child (a boy). However, ‘[t]he giant got tired of this very soon | And left him under the silver moon’. The lost child then beats a retreat. ‘I need not say he came home very fast | And was safe in his mother’s arms at last.’ In some ways the ending is the very

opposite of ‘Who Did That’, where ‘the very big’ girl ends up fretting guiltily about her absent mother. The silver moon serving as picturesque decoration in Amy’s poem attains to a symbolism of apprehension in Roberty’s. Given similarities in form and content, it would seem that ‘The Lost Child’ served as the exemplum at hand for ‘Who Did That’. Other evidence prompts the reasonable speculation that not only Roberty, but all of the children were engaged in writing it.

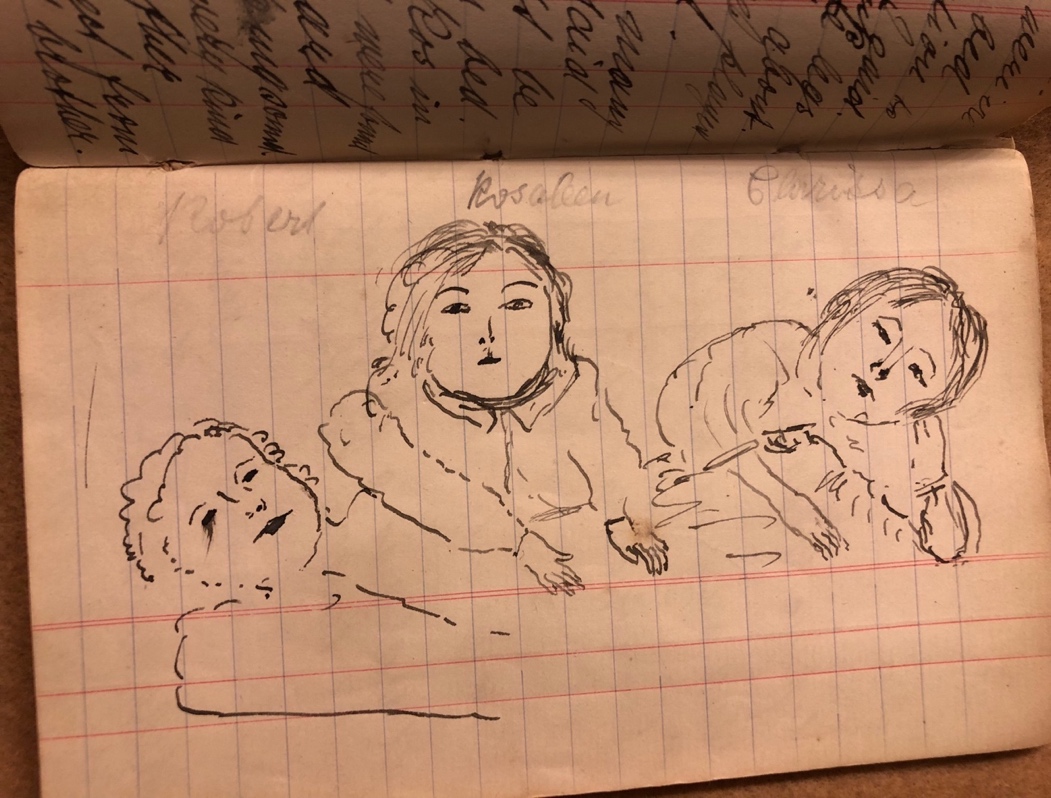

Take the evidence of handwriting. There seem to be three separate hands at work here. There is a careful hand responsible for line one ‘Who did that?’ which superficially resembles Amy’s handwriting; there is the less careful hand responsible for ‘Said’ on line two, with the large print ‘S’, and other details; and a very childish hand responsible for the heavy ‘My dears’ on line fifteen, the illegible ‘fears’ on line sixteen, and the chaotic ‘Wimbledon’ with the extra hump in the ‘m’, on line nineteen. It’s conceivable that Amy started the poem, wrote out the first line (the elegant Upper Case ‘W’ in ‘Who’ looks like the penmanship of ‘The Lost Child’), and then gave the Song Book to the children, to write lines or couplets, either as they conceived them or as they were called out. But the neatest penmanship is not convincingly Amy’s: the characters are rounder, less slanty and condensed than those in ‘The Lost Child’. It may be that the situation of writing the poem as a performance dictated that she write differently, perhaps more slowly. However, an obvious, and I think better counter-theory would be that the superior handwriting was Clarissa’s, age seven; Rosaleen, age five, would have had the less practiced hand, and Roberty, not yet four, the shakiest. That ‘Who Did That’ is written in erasable graphite pencil rather than pen inclines me to believe that Amy expected the children to belabour the poem. (Perhaps Graves’s first experience writing a poem was also his first rewriting.)

Additionally, evidence suggests that one of the sisters corrected the text at some point. To take two examples: the word ‘Wimbledon’ seems to have been finished by a surer hand; the

upper case ‘T’ on line seven has been altered; and the disproportionate comma on five seems to have been added by a heavier pencil. Some words seem to have been added: on line two, ‘Said’ with a print capital ‘S’ is in a markedly different style from the rest of the line: the letters slant in different directions (the upper case ‘S’ seems almost block-printed), and it incorporates a lower case ‘a’ that is distinct from the ‘a’ in ‘cat’. The cultural trend away from the slanting cursive hand toward a vertical orientation with letters resembling their print counterparts seems to be operating here. Erasure marks appear to be present, too. Also ‘into’, on that pivotal line nine, seems to have been fixed or tampered with, the ‘o’ nimbly inserted for clarification. I think it possible some of the words in this second part of the poem could have been Roberty’s first stumbling efforts at handwriting. This speculation s prompted by the sudden wildness of the hand, which appears intermittently to the end of the poem; could Robert, possibly absent from the poem until now, suddenly have taken hold and run with it? It’s possible that he was inspired by watching his sisters invent couplets or even by the beatings he vicariously suffered in ‘The Lost Child’. He may even have been inspired by a spirit of reciprocation: Amy had cast him out into the world to be beaten by a giant, and now he was going to cast her out. Certainly ‘the Silver Moon,’ which in Amy’s poem lacks emphasis capitals, was on his mind.

In addition to the childish brutality of the handwriting, certain mannerisms in ‘Who Did That’ differ notably from ‘The Lost Child’. For example, where Amy’s poem repeats ‘and’ to link together actions, ‘Who Did That’ uses ‘then’, which suggests that the children were imitating ‘The Lost Child’ without Amy’s help or with only minimal help, building up the poem as they went along.

Another clue that the children were collaborating can be deduced from a page of short poems that appears a few pages later in the Song Book. Each one is headed with one of the children’s names, a date (‘99’), and the word ‘alone’. Although they appear to have

all been transcribed by the same neat hand (making the page resemble a fair-copy rather than an original manuscript), the headings tell us that each poem was a solo effort. Roberty’s poem amounts to one couplet, pointing incriminatingly back at ‘Who Did That’. ‘My fingers are tall | And I put my soapy finger on the wall.’ If it was important to designate each poem as the work-product of one child ‘alone’, this could be because the children had previously written collaboratively, perhaps with some unavoidable tension seeping into the finished poem; now they wanted complete credit for their individual efforts. The name ‘Robert’ above ‘Who Did That’ (not ‘Robert alone’) strongly suggests that he was predominantly responsible for the poem, but not the only author: most likely the most active and enthusiastic of the three. More evidence of multiple-authorship comes in the form of another Song Book poem, untitled, written in a childish, uneven, script in blue pencil, bearing the same thematic concerns as ‘Who Did That’:

I’m in the bog

Said the big dog,

You don’t say that?

Said the cat.

I’m chasing a hare

Said the grown-up bear

How hungry I am

Said the [little?] lamb

I’ll give you some food

For I am not rude [I’m?]

I’ve got some kippers

Also some slippers

Look at our pen

Said the cock & hen

I see some peel

Said the <crossout>slimy</cross> [chubby? | cheeky? |

I am here

And I’ll drink some beer.

A man with a gun

Then ended the fun.

Following this poem, probably another collaboration, come more verses in blue pencil. While the penmanship is less accomplished than the chief hand (the older, Clarissa’s?) of ‘Who Did That’, and while it could be Robert’s, it’s probably Rosaleen’s, who developed her own interest in poetry, which Clarissa did not.

It’s not impossible that Robert was the sole author of ‘The Big Dog’ (above), but safer to consider it a team effort; (striking out ‘slimy’ for a more suitable adjective suggests the children used a similar editorial practice in ‘Who Did That’, but there, as Amy may have directed them, they employed an eraser). Two blue pencil poems immediately following the ‘The Big Dog’, entitled ‘Winter’ and ‘Spring’,

Two little flowers

In the bowers

Finally, the last entries in The Red Branch Songbook are dated much later (e.g. ‘Rosaleen, Feb. 3 1905, aged 10’). So it would appear that Rosaleen held onto the Song Book after the others lost interest and it continued to nurture her poetic ambitions. I believe it was she who corrected some of the earlier work. Her upper-case ‘T’ in a long poem entitled ‘Scarlet -fever-poem’ resembles the upper-case ‘T’ in the line, ‘Then into the room,” in ‘Who Did That’, further evidence that the neatest hand in the poem is not hers. It may be that Rosaleen made her corrections some six years after the fact, possibly proud of what the siblings had done together, and recollecting the fun they had that long-ago day in her lost childhood when Amy put away the book of nursery rhymes, demonstrated that Alfred need not be the only poet in the family, and insisted that they, too, could write a poem. In which case, the final answer to ‘Who Did That’ would be . . .

‘Robert, Rosaleen, Clarissa’, page from Red Branch Songbook (The Henry W. and Albert A. Berg Collection of English and American Literature, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundation

Michael Joseph is the editor of Gravesiana: The Journal of the Robert Graves Society.

NOTES

Lady, lovely lady,

Careless and gay!

Once when a beggar called

She gave her child away.

The beggar took the baby,

Wrapped it in a shawl,

‘Bring her back’, the lady said,

‘Next time you call’.

Here, the casualness with which the mother treats the child – and perhaps the child’s regression into a ‘baby’ – again echoes Lewis Carroll.

I would suggest as a simple test for whether a poem is to be regarded as Romantic as

Now

All the pretty flowers gone

The leaves have

Changed from

Green to red

The snow is on

The flower bed.

How dull & short

In the wintry day

I wish [the?] winter

Would not stay

Christmas day is very nice

And we may skate

Upon the ice.

[next page]

Spring

All the snowdrops now

Are glowing

And all their [polished?]

Leaves are showing

The swallows now

Have come again

No Spring flower is

A […] bit [vain?]

Pretty though the

Flowers are

Like a god or silver star

But the tale is finished now

I heard a dog say

bow wow wow