|

Search Help |

|

Links Robert Graves Website Other RG Resources |

Critical Studies

Versions of Robert Graves

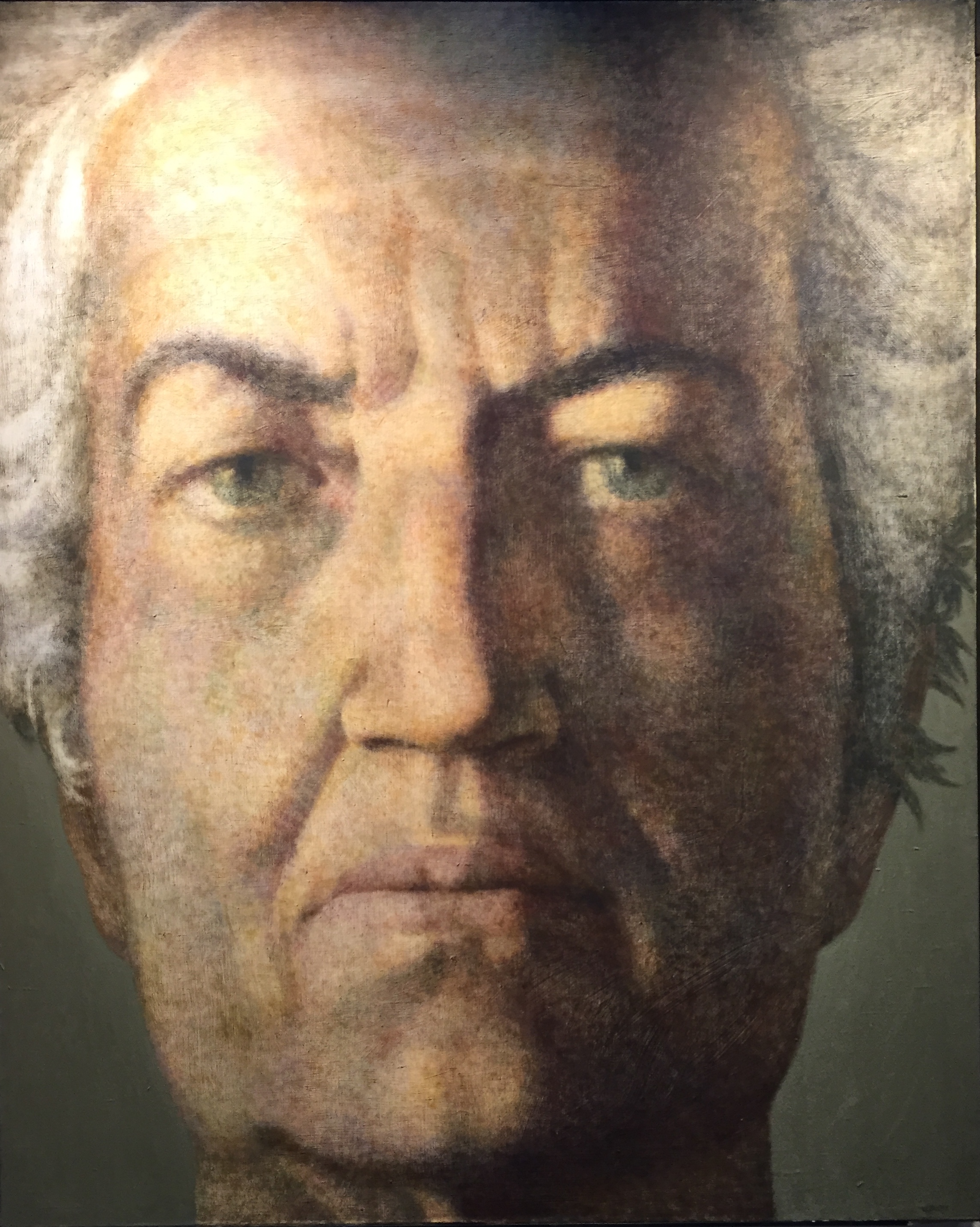

John Ulbricht, Portrait of Robert Graves (1968) Image courtesy the Poetry Collection of the University Libraries, University at Buffalo, The State University of New York. I first encountered poems by Robert Graves in Kenneth Allott’s 1950 Penguin Book of Contemporary Verse, like Michael Longley, who quotes Allott in the introduction to his Faber selected Graves: ‘The poetry of Robert Graves is in some ways the purest poetry produced in our time’. I was seventeen, in my last year at school in New Zealand, when I read this assessment. Allott also predicts: ‘The bibliography of his poems is sure to provide headaches for future scholars’ (p. 109). My own headaches, both physical and figurative, started thirty years later, when Beryl Graves and I began work on what eventually became the three-volume Carcanet edition of the Complete Poems, and the Penguin Classics edition. From the Allott selection I went on to further poems by Graves in the Faber Book of Modern Verse, and then to Graves’s own Penguin selection, in the revised and enlarged edition of 1966. My copy is dated 1968, the first year of my academic career. I was reading it in the Waikato University library when Vincent O’Sullivan, today one of New Zealand’s most celebrated writers, paused at my table: ‘Ah, I see you’re a Robert Graves man. We must talk’ – and we’ve been talking about Graves ever since. I pursued my interest in Graves’s poetry after I moved in 1971 to London, and then in 1973 to Paris. Settling into a new apartment in the Faubourg Saint-Germain, I pinned above my desk a pensive photo of the poet in his familiar black hat. I made my first visit to Mallorca in July 1989. It was, in a sense, a pilgrimage. I wanted to see the village of Deyá where he had lived, the Mediterranean scenery he evokes in his poetry. A mutual friend put me in touch with Graves’s youngest son, Tomás, who told me that a neighbour, Robert Edwards, might have a room available. Edwards was a retired English civil servant; he had known Graves during the last, declining years of his life. I met him on 9 July at a bar in Deyá; in my diary I noted: ‘70s, white spade beard, short, pot, watchful amiability.’ We reached his house via a long twisting stepped path down a terraced hillside. ‘A simple strong-lined stone farmhouse, the form typical of those on the hills around, Roman tiles, green shutters, flagged floors.’ Its name was C’an Pa Bo, ‘the house of good bread’. Edwards told me that Graves and Laura Riding had lived in C’an Pa Bo while their own house, Canellun, was being built. The upstairs room I chose had in fact been Graves’s; I would even be sleeping in the same bed. From the jasmine-framed window, which gave a splendid prospect of the mountains enclosing Deyá, I could see Casa Salerosa, where Graves and Riding installed themselves in 1929, sixty years before. About 6.30 next morning I walked up to the church crowning the hill above the village. From the cemetery there was a beautiful view of sea, beyond a long terraced valley, the sun not over the hilltops yet, though the sea already glowing. Found Robert Graves’s tomb, after searching in vain for a bust or monument. Instead there’s just a flat cement slab, slightly thicker at the top end and therefore slanting, with the inscription scratched with a stick, apparently, while the cement was still wet: ‘Robert Graves / Poeta / 24.7.1895 –7.12.1985’ (the ‘24’ evidently a correction after an initial mistake), written in a laboured, ingenuous longhand. There were some scraggy little bushes planted round the edges, and a bunch of carnations, now dead, wrapped in plastic and thrust into the neck of a jar. The stone is at a slight angle to the others in the graveyard; at its head there is a fine tall cypress. […] I knelt at the graveside and said a prayer. In coming to Mallorca, I had no intention of intruding on the Graves family. I hoped at best to be able to see his house from the road, as my mother had some years before, catching a glimpse from the coach windows of the poet in his garden. However, a week after I arrived, I wanted to check some allusions in the poems I was reading and asked Edwards if he had a copy of The White Goddess. He didn’t, but suggested that I might be able to borrow one from Mrs Graves. We called in next morning on the way to Soller to do the shopping. As we went up the path through the garden she came to greet us, accompanied excitedly by her shaggy black-and-white dog, Sharik. I was impressed by Canellun: ‘It’s a big house, two storeyed, […] stone, of course, a fine large garden with terraces, and seats and tables at various points, lots of trees and shrubs. Good pictures, ceramics, etc. inside, plain furniture.’ The copy of The White Goddess that she lent me was Graves’s. We were talking of him when Natalia Farran came through, the young girl with long dark hair I’d sighted lying on the rocks and chatted with during a swim along the coastline. She turned out to be Beryl’s grand-daughter, and she was preparing material for a reading devoted to Graves’s ‘Last Poems’, work he hadn’t published in book form before his death. My diary continues: Natalia went back to her work and Beryl clearly wanted to resume hers, so she and Robert Edwards started moving out, but fearing to miss the opportunity more than the risk of seeming ‘pushy’, I asked if I could see Graves’s study. She was quite willing, though it had to be quick. She took me through the house to a shaded, cool room at the back. A big wooden desk with space to sit at either side […]. Lots of small objects, including statuettes, on the mantelpiece […]. Many more objects around the room which I longed to inspect but hadn’t the time to even register before she ushered me out again. She joked about what Graves’s reaction would have been to the word-processor on his desk; a poem had been partly printed out. In the garden Robert Edwards and she spoke of the reading, rather nice hand-painted posters for which Natalia had shown us. Then we said good-bye to her at the gate, and we headed off to Soller […], The White Goddess under my arm. The poetry reading and concert took place on Sunday the 23rd, the eve of Graves’s birthday, maintaining a tradition established during his lifetime – he would often write a play for the occasion and act in it himself. With my brother Reg, who had just come over from Madrid, Edwards and I met Beryl on her way down to the small open-air amphitheatre in the field opposite the house. The poems were read by members and friends of the family. I was sitting next to Beryl and asked her about the texts. She said the originals were up at the house: would I care to look at them? On the 24th there were fresh flowers on Graves’s tomb. Two days later, on the Wednesday, I went to Canellun with Reg (when I asked Beryl if I could bring him, she answered, after a moment, ‘I think that would be in order’). She led us through to what she called the Press Room, where Graves, Riding and Len Lye produced their remarkable Seizin Press editions, and where Graves died, as I learnt later from Natalia. Beryl showed us manuscripts and typescripts of the poems we had been listening to. It was an unforgettable experience to see and to hold, for the first time, a sheet of paper with a poem on it in Robert Graves’s handwriting. We went back again on the Friday, my last day in Mallorca. Beryl was seated in the Press Room at the heavy wooden table, which was scattered with manuscripts of poems that she was in the process of sorting. What with the heat, and the children and visitors, she said it was difficult to make any progress. While she was out of the room getting us some lemonade, I said to my brother that she obviously had too much to do. ‘I’d love to offer to give her hand.’ ‘Then why don’t you?’ ‘There are other people who would be better qualified to do it.’ ‘Are there? Who?’ ‘Well, Vincent, for example.’ ‘Perhaps, but he isn’t here, and you are.’ So, when she returned I asked her if perhaps I could come back in a month’s time and help. She was happy with the idea. A little later Lucia appeared at the door. ‘Darling, this is Dunstan,’ Beryl told her. ‘He’s going to help me with the manuscripts.’ Lucia looked at her and raised her eyebrows; her mother nodded firmly, and Lucia smiled. On 5 August Beryl wrote to me in Paris about obtaining copies of poems printed only in magazines. Her letter ends, ‘I can’t tell you how relieved I am that you are coming back in September.’ Over the next eight months I underwent what I realised in retrospect was an ideal intensive training course in editing Robert Graves’s poems. Among the manuscripts at Canellun were the drafts of dozens of unpublished poems, and many more unfinished poems and fragments. For each of these poems, I went carefully through the drafts, often numerous, and put them in order, by tracing successive revisions. In so doing I was able to study the process of Graves’s composition from within, to examine how his changes improved the poem, strengthening its inner logic, bringing out latent content, sharpening imagery, and tightening rhythm. I learnt the characteristics and quirks of his handwriting. On the back of each draft I pencilled its number in the sequence. When I’d established which was the latest version, I dealt with any anomalies of wording, punctuation, layout, etc., by referring back to the preceding drafts. I discussed the outcome with Beryl and Lucia, and once we had a ‘final’ version Beryl typed it out. From some fifty poems that emerged, Beryl made, in April 1990, a selection of fourteen, with eight that I’d heard at the birthday reading. We agreed on the order, and on a title, that of one of the poems: Across the Gulf. A limited edition of 175 copies were beautifully printed and bound by Tomás Graves and his wife Carmen García-Gutierrez at their New Seizin Press. All Graves’s books of poetry were in his library at Canellun, and during the following two years (Lucia and I having embarked on another literary project, a Spanish edition of short stories by Katherine Mansfield), Clearly, the whole corpus of Graves’s poetry had to be republished. Only then would it be possible to make a just appraisal of his work, and to affirm his status as a major twentieth century poet. But how would Beryl view this proposition? And Graves’s son William, his literary executor? During the Robert Graves birthday celebration in July 1992, I took part with my brother in a performance of the opening scene of Graves’s 1930 play, But It Still Goes On. A few days later, on 29 July, Beryl and I were looking at books and manuscripts of poems in Graves’s study. As my diary records, I suggested that what was needed was a complete Poems, with a minimum of notes, etc.; that much of his work was out of print, inaccessible, and/or weeded out by Robert Graves; that many reviews, Carter’s book, etc., referred to this. I suggested we should begin ourselves […], with the aim of getting it published in the anniversary year, 1995. She agreed at once (i.e. as soon as I’d explained what I meant), as did Lucia next day when Beryl told her. Lucia said Beryl thought we should go ahead and worry about a publisher, etc. later. We decided it would be best to bring the subject up with William next time he was at Canellun for, say, afternoon tea (rather than going deputation-wise up to the Posada). – and approved. My diary continues: I started the following day looking at the earliest vols (Beryl’s proposed procedure – book by book, in chronological order). After supper […] she got out of the chest the library’s [copies of] Over the Brazier; Fairies and Fusiliers; Treasure Box; Hogarth Press editions including The Marmosite’s Miscellany (these were from 1920s, published at Tavistock Sq.) Wonderful. Am going back in September for two weeks working on the project. From the outset, some crucial editorial issues had to be addressed. There was surely a strong case for an edition containing all the published poems. In the course of preparing each of his seven volumes of Collected Poems from 1926 to 1965, Graves suppressed a substantial proportion of his work. ‘A volume of collected poems should form a sequence of the intenser moments of the poet’s spiritual autobiography’, Graves states in the Foreword to Poems and Satires 1951. In continually reshaping the canon, he was creating different versions of his life story (‘It is myself that I remake’, as Yeats put it). By 1965 little more than a third of the pre-1960 poetry was left in the canon. The range had been narrowed, and some of the finest poems removed. In failing health, Graves could not continue thinning out his poetry for Collected Poems 1975, which reprints the 1965 volume intact and adds 270 more poems written since then. This was Graves’s eighth Collected and by far his largest: 633 poems, 592 pages. It was his last book. The 1975 canon was ‘top-heavy’, as Paul O’Prey observes in his ground-breaking 1986 Penguin Selected: The Introduction to Volume I of the Complete Poems begins: ‘The aim of this edition is to make available, for the first time, all the poems that Robert Graves published, together with a selection of his unpublished work.’ Were we justified in printing poems that that the poet himself rejected? In Beryl’s and my judgement, we were. Graves acknowledges, in that same Foreword to Poems and Satires 1951, that editors of future anthologies ‘may even choose to revive verses which, because I know that they are in some way defective, I have done my best to suppress’. Moreover, his own practice wasn’t wholly consistent: the 1951 book actually contains four poems ‘more than twenty years old’ which he omitted from the 1948 Collected. In the 1929 Good-bye to All That he dismisses ‘In the Wilderness’, his popular poem about Christ, as ‘a silly, quaint poem’, Counting the four in Poems and Satires 1951, Graves restored some forty earlier poems in books published from 1943 to 1964; in 1958 he also sent a typescript of seventeen poems for an anthology, Seeds in the Wind: Juvenilia from W. B. Yeats to Ted Hughes, edited by Neville Braybrooke. (It finally appeared in 1989, with three of Graves’s poems in it.) Another consideration was that while Graves claimed he did his best to suppress poems, he still kept every set of proofs, every draft, even if written on a bit of wood he picked up at the beach or on the back of an in-flight drinks list. He consigned a vast quantity of manuscripts in 1959 to the State University of New York at Buffalo, which formed the basis of its Robert Graves Collection, and further batches went to other North American libraries. Fifteen suppressed poems had already been revived by O’Prey in the 1986 Penguin Selected, and a body of war poetry by William Graves in the 1988 and 1990 editions of Poems About War. In the Complete Poems we decided that the order of the poems should correspond to the first editions of Graves’s books, but that the texts of the poems should be the last versions that he approved. ‘My poetry-writing has always been a painful process of continual corrections and corrections on top of corrections and persistent dissatisfaction’, Graves wrote in Good-bye to All That. In the notes to our edition we recorded all the differences – changes in wording, punctuation and layout, deleted lines and stanzas – between the first book version and the last (plus, exceptionally, important intervening revisions). The edition thus reproduces two complete versions of the poems. For the latest versions, textual anomalies, misprints, etc. were corrected in the light of previous printed versions and manuscripts. These emendations are recorded in the notes. The notes also give background information on the poems, with quotations from and/or references to other poems by Graves, and his letters, diaries and prose writings. Three scholarly works proved indispensable: the Higginson and Williams bibliography; the Selected Letters, edited in two volumes by Paul O’Prey; and Richard Perceval Graves’s three-volume biography. Establishing the texts and writing the notes was a lengthy and painstaking task. We kept to a procedure from the beginning. Beryl and I each prepared notes on the poems, listing the variants, and then I collated them and made a finished version. I drafted the notes on each of Graves’s books, and the introductions to the three volumes of our edition. We discussed everything together, and she read through and commented on everything I wrote. Her comments were normally approving and encouraging, though from time to time she would protest about my detailed references: ‘Do we have to put that? Surely they can look it up for themselves?’ I recall only two serious disagreements. One was about ‘Rocky Acres’ (‘The first poem I wrote as myself’, Graves termed it). At Canellun I had the privilege of working at Graves’s desk in his study, where I could consult his annotated copies of his first editions, and the reference books that he had used. Beryl worked in the Press Room adjoining the study, except when she was typing upstairs. She insisted on typing out every one of the 1202 poems herself. That way, she said, she could get inside them. I wrote everything in longhand and Beryl typed it up, or I did so in Paris. For the finished texts of the books we initially used an Amstrad computer, exasperatingly slow and cumbersome (six separate manipulations were required to go into italics and come out again). For Volumes II and III we graduated, thanks to William, to a PC. An essential part of the project consisted of preparing lists of manuscripts of published and unpublished poems and printings in periodicals, and ordering copies from collections in libraries, principally the Robert Graves Collection at Buffalo, or photocopying them ourselves. Lucia played a vital role in all of this. Sixteen months after we started work on our edition, William phoned me in Paris, on 20 November 1993, with news of a breakthrough: Michael Schmidt, of Carcanet Press, was going to publish the poems, together with most of the prose titles, in a so-called Robert Graves Programme. Over the following six years Beryl and I maintained our editorial routine. I spent all or part of my university vacations – in February, the spring, the summer, November – at Canellun. I slept upstairs in what once was Riding’s workroom. There was a view from the table by the window across the olive trees and cypresses to the sea. Beryl had breakfast first; I would come downstairs to find coffee made and my place set at the kitchen table, with perhaps a book which she’d promised to find for me. We worked steadily all day; one long humid summer I took only four days off. ‘You must go out,’ Beryl would say to me towards the end of the afternoon, and I’d go for a walk above the cliffs and, in warm weather, swim off the rocks. During the summer Lucia used to drive Beryl and me down to the Cala for a morning bathe. Beryl did the cooking, on a venerable Aga supplemented by a stove outside the kitchen door. She had a repertoire of tasty dishes, including an exemplary gazpacho. On fine nights we dined out on the terrace, maybe in the company of visiting family or friends. From time to time we would eat in the village or at one of the two fish restaurants down at the Cala, or, on special occasions, at an excellent clifftop restaurant, Bens d’Avall, off the road north to Soller. In the evenings we played countless games of Scrabble. Early in June 1994 I went to the village of Kirtlington, near Oxford, to discuss our edition with the General Editor of the Robert Graves Programme, Patrick Quinn. Patrick was part-American, part-Canadian, a lecturer at Nene College of Higher Education, later the University of Northampton. He was editing a new selected Graves for Carcanet, Thanks to a British Academy grant, I was able to travel to the United States in April 1995 to do research on the Graves holdings at the State University of New York at Buffalo and the Berg Collection at the New York Public Library. My reception at Buffalo was a testing one. I was directed to the office of the Curator of the Poetry/Rare Books Collection, Dr Robert Bertholf, to whom I’d written about the Complete Poems edition. Bertholf was a professional editor, specialising in the poetry of Robert Duncan. ‘They’ll crucify you’ were his first words to me. I responded that I believed our editorial approach to Graves was valid. He gave me a pile of photocopied articles and chapters from books by the current authorities on textual editing and criticism, and I passed some rather fraught hours that night reading through them in my funereal motel room. Was printing the poems in the latest versions a hubristic blunder? When at last I went to bed I was feeling somewhat reassured. Our editorial decisions appeared to be supported by, or at the least compatible with, everything that I’d read, in particular Jerome K. McGann’s critique of the long-ruling Greg-Bowers theory of scholarly editing with its emphasis on early rather than late states of text, and McGann’s preference for versions rather than eclectic (multiple source) editions. In the morning I put this forward in detail to Robert Bertholf. He was convinced. The library’s Graves material and his staff were at my disposal. From then on Bertholf, a warm-hearted, enthusiastic scholar, provided invaluable support for the edition, together with his assistant and eventual successor, Michael Basinski. Mike would wheel out trolleys of manuscripts from the air-conditioned room in which they’d been preserved in special folders since their delivery from Mallorca, where they’d lain for months in a dusty shed after being transported there by donkey-cart. I spent a busy week studying the manuscripts and making notes in the pleasant oak-panelled library, under the disquieting gaze of Robert Graves: a huge portrait by John Ulbricht showing only that formidable head, considerably larger than life, as indeed was Graves himself. I returned to Buffalo and to the Berg Collection in 1996, to study manuscripts of poems for the second volume, covering the years 1927 to 1959, and to seek out unpublished poems for the third. There were some moving relics at Buffalo, such as Graves’s army satchel, and the volume of Keats, inscribed in 1915 by ‘his affectionate father’, which he carried with him in France. Volume I of the Complete Poems appeared in November of the centenary year, 1995. I gave a talk about the edition at the centenary conference at Oxford in August, at Graves’s old college, St John’s. ‘It was lovely’, Beryl said afterwards. ‘You were noble.’ Amid the generations of Graveses at a memorable garden party were his daughter Catherine and his son Sam, and his niece Sally Chilver. In the TLS the poet Neil Powell described Volume i as ‘a revelation’. To begin to understand Graves it is vital to understand the nature of his passion for revision. It sprang, paradoxically, from a belief in inspiration. Graves, more than any of his contemporaries, had a strong sense of a poem as something ‘given’. The poet’s initial task is to be open to the possibility of being inspired, then to act as a kind of secretary to hidden powers, finally to work on what those powers give him until the result is linguistically and rhythmically as exact as he can make it. At the root of this process is a belief that the poem, the thing made, has a life of its own which might be more enduring than the poet who makes it. Volume ii of the Complete Poems was published in 1997. ‘The editing is admirable’ Robert Nye wrote, again in the Scotsman; in Poetry Review Neil Powell asked: ‘Will they at last prove to be the twentieth century’s finest body of English lyric poetry?’ Volume iii included sixty-nine of Graves’s unpublished poems, fourteen of them from Across the Gulf. In selecting them, we gave priority to poems whose publication had been approved by Graves but was prevented by some external factor (in one case, cuts wanted by the wartime printers), or poems that had been treated by Graves as finished. At the launch party in November 1999 at Lucia’s house in Putney, Carcanet was represented by Robyn Marsack, our patient and understanding editor; she ended her speech by proposing a toast to Beryl. The Carcanet Complete Poems in One Volume appeared in 2000, and the Penguin Classics edition of this in 2003. All five books received extensive and favourable reviews, including a six-and-a-half-page review of the three-volume edition by Ronald Gaskell in the authoritative journal Essays in Criticism, which concludes: ‘I have hardly been able to suggest the range and quality of the editorial notes that buttress each volume of the Complete Poems. […] If any […] revaluation [of Graves’s poetry] is to be undertaken seriously, the three Carcanet volumes will be indispensable.’ The Penguin Classics volume has made the poetry accessible at last to the general public, as has Michael Longley’s superb Faber Selected Poems, for which he used our texts. I regretted, of course, never meeting Robert Graves. When I once said this to his son Juan, however, he replied that perhaps it was for the best; by the 1970s his father was fading, and I wouldn’t have met the man as he had been. Yet at Deyá Graves was still everywhere around me: in his study, amidst his books and treasures; on his walks through the olive groves; at the Cala, where he used to dive off the high rocks for his daily swim. In the summer I helped Beryl water the fruit trees and flowers and vegetables in his garden and tend the descendants of his compost heaps. In one birthday play I wore his striped waistcoat. I had resolved from the beginning not to take advantage of Beryl’s hospitality and friendship to enquire into her personal memories of Robert (which, from early on, she allowed me to call him). Nevertheless, reserved as she was, very much a private person, she would occasionally speak directly of him: the way when travelling he would strike up a conversation with complete strangers; or take a tasty-looking piece of food from somebody else’s plate; or how he liked washing the dishes, as it helped him to think about what he was writing; or his custom of bowing nine times to the new moon. Lucia, too, would tell me about her father, whom it was clear she had loved unreservedly. My favourite story was how, when she was upset as a child by a nightmare, he would pretend to search for it on her head until he cried ‘I’ve found it!’ and took it to throw it down the loo. Natalia recounted that in his old age her grandfather could get angry if she and the other children made a noise ‘while he was thinking’; once he shook his stick at them, but later came out again and gave each of them twenty-five pesetas, to make up for it. And Graves himself would sometimes suddenly appear, startlingly realistic versions of him, in the features of William or Juan. But it was Lucia, I thought, who seemed to have inherited the poet’s aura. Beryl and my mother became good friends, writing to each other and exchanging gifts. They shared a love of reading and gardening. On one of my mother’s visits to Canellun, while Beryl was talking with my sister Ann in Graves’s study about my work editing the poems, Beryl said, ‘He has brought Robert back to me.’ This article is based on the text of the Robert Graves Society Talk given on 11 July 2018 during the Fourteenth International Robert Graves Conference at Palma and Deyá, Mallorca. Dunstan Ward is the co-editor of the three volume The Complete Poems of Robert Graves, and author of a volume of original poems Beyond Puketapu (2015).

NOTES