|

Search Help |

|

Links Robert Graves Website Other RG Resources |

Historical Trace

Interview with Ruth Fainlight

CM: Ruth, thanks very much for agreeing to talk about this period in your life. First of all, I was wondering how you encountered Robert Graves for the first time, and where.

RF: Alan [Sillitoe] and I had gone to the south of France – Menton – very near the Italian border at the beginning of ’52, and I already knew about Robert Graves. I was very young then; I was less than twenty-one. I know I was less than twenty-one because while we were in the South of France I went to – where is that people go to gamble?

CM: Oh – Monaco, Yes?

RF: Yes, that’s right; but they wouldn’t let me into the gaming rooms because I was under twenty-one, you see, so that’s how I can remember my age. Then I went back to England to do something, and while I was in England (because I stayed there longer than I expected to, for some months), Alan moved to Mallorca. Some people we’d met in France had moved there already and told him how wonderful it was and that it was much cheaper than in France, and as we had very very little money, that was an important factor. And the fact that Robert Graves was in Mallorca made it much more interesting than just the fact that it was cheaper. And before I rejoined Alan, he had already made contact with Robert Graves, so Alan met Robert Graves before I did. Alan has written about it in some autobiographical piece: his – what’s the name of his autobiography?

CM: In Life without Armour?

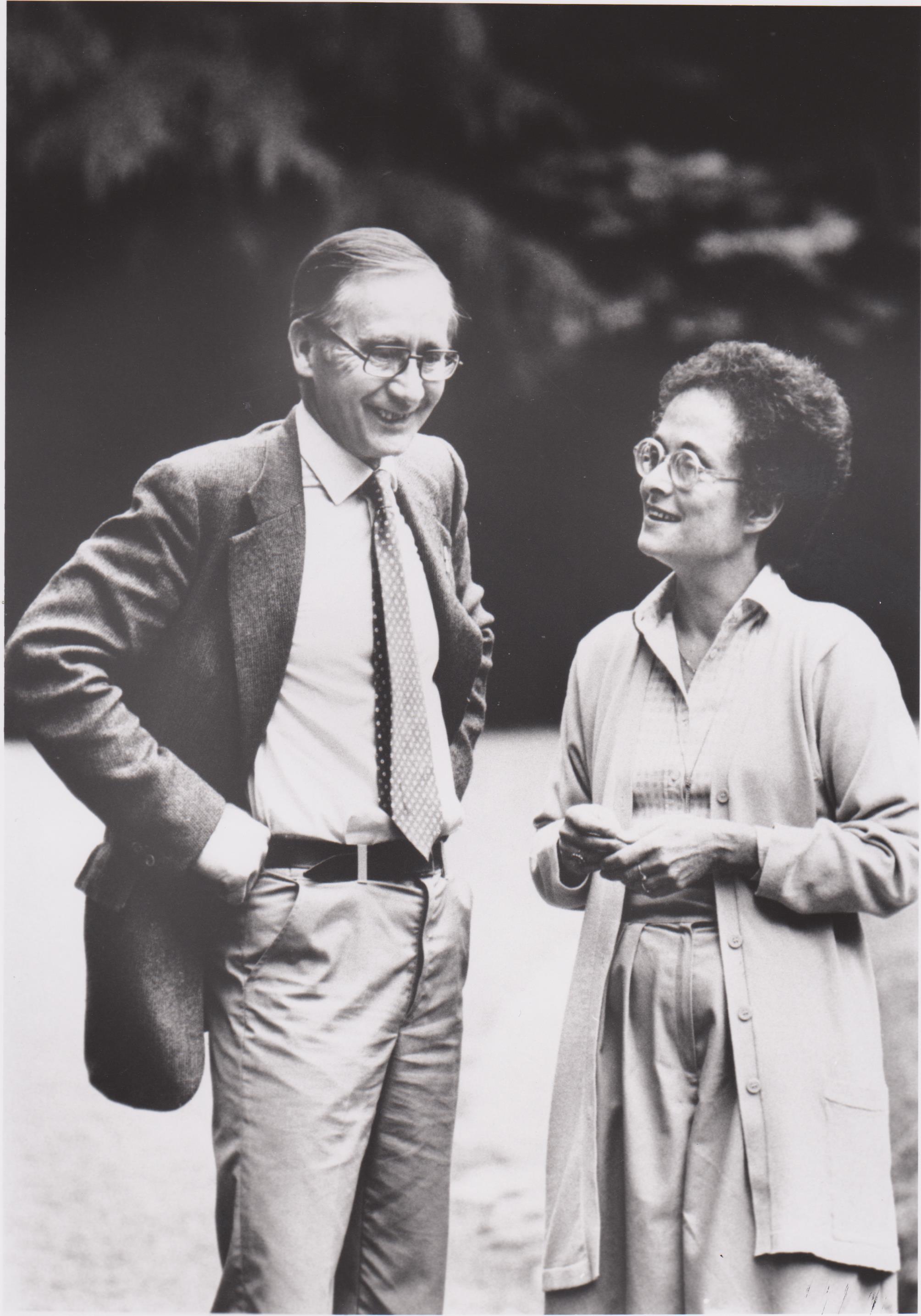

Ruth Fainlight, photograph by Emily Andersen

RF: Life without Armour! I think it’s in there, the description of him going over. I think he borrowed a bicycle to get over to Deià from Sóller – it’s about ten kilometres. Anyway I wasn’t there. And so I met Robert Graves as Alan’s partner. I already knew about Robert Graves as a poet, and as the person who had written The White Goddess and various historical novels, but I’m trying to recollect how I very first heard about him. Certainly I’d already read many of his poems and had bought a copy of The White Goddess and tried to understand it, and admired him immensely.

CM: You were speaking yesterday about that being an early important book. Was it a book that you had encountered at college or earlier?

RF: I came to England when I was fifteen and I did – it was School Certificate then – and it was the equivalent of O level, although I think it has another name now. I went to a grammar school in Birmingham and I would have liked to have stayed into the sixth form but it didn’t work out that way. So it wasn’t a question of learning about him at school . . . that’s why I’m labouring the point because I’m trying recollect how it could have been. I mean when was The White Goddess published?

CM: 1948, I think.

RF Yes, well 1948. [Pause] I came to England in 1946, yes, so . . .

CM: So, it was around about that time, but difficult to pin down exactly when?

RF: Yes.

CM: Ok, yes; and what did you make of Robert Graves when you first met him?

RF: You mean as a person?

CM: Yes.

RF: Well first of all, I’d read about him and Laura Riding, and I found this so exciting and romantic, this pairing of two poets; and obviously I didn’t know much about them, but it was just the idea of these two poets living in Mallorca, and there were Alan and I in Mallorca and we were two poets. Of course, they were older. I mean Robert Graves was already married and a father and so on and so forth, so there’s not that much comparison at all, but I don’t know if it’s unusual, but an adolescent poet wants to have models, heroes, yes.

CM: Yes. And you obviously both found that Graves was in a way not so much willing to play that particular role for you but was very welcoming and engaging. Was he encouraging of your writing?

RF: I don’t think he took me seriously at all. I wasn’t excited by him as a man and I don’t think that he was . . . that he responded to me. I wasn’t one of the young women who went to Deià and fixated on him – it wasn’t like that: I respected him as a poet. I didn’t somehow imagine that I’d get into any personal relationship with him. I didn’t want to and I wasn’t, it didn’t arise. But, yes.

CM: And at that point I would imagine that you were perhaps reading more of Graves’s poetry. Did he talk to you about the process of writing poetry at all at any point?

RF: Yes. You see at that time the Graves family lived in Palma during the school year because the children went to school in Palma, and they lived in Deià during the summer holiday. We’d see them in Palma because of Alan, really. We were living off a pension because of his tuberculosis. He was in the RAF in Malaya and when he came back to England it was discovered that he had contracted tuberculosis, so he went into a sanatorium for about a year or eighteen months. He was just out of the sanatorium when I met him.

CM: It sounds like you were very much aware of Graves the writer and Graves’s reputation.

RF: Yes, but also, you see, I didn’t want my parents to know that I was living in Mallorca with a man . . ..

CM: No [laughs]

RF: . . . so I made up this story that there was this famous poet Robert Graves, and that I would probably be able to get a job doing some sort of secretarial work for him. He was a factor already before I even went there. I knew about him and I knew that he had a reputation as a poet and that this might be plausible.

CM: You were using him as cover!

RF: That’s right, that’s right.

CM: Very good!

RF: Alan had to go to a doctor in Palma – he was having treatment which was being paid for by the British government. It was extraordinary. We were living off a pension, a minute income, £4 7s. 6d. a week I think, and we were really very skint. But at the same time, his medical treatment was being paid for by the British government. As he said, he was being kept by a woman – the Queen [laughs]!

CM: Quite right, too!

RF: Quite right, absolutely. So what it meant was that every three weeks he was having a treatment called artificial pneumothorax, which is that air was pumped into his chest cavity to flatten one lung which hadn’t healed properly yet. So he’d go to this doctor who was a Mallorcan doctor, but paid by the British government there must have been other pensioners on the island who were being looked after who had different medical conditions. And what it consisted of was, air would be pumped into his chest, and it would flatten the lung; and then, during the course of three weeks, this air would come out of his mouth or through his skin and slowly the lung would reflate, and at the end of three weeks he’d go back and have the treatment again. So this was an absolutely regular trip from Sóller to Palma taking that nice little train.

CM: Oh, yes.

RF: And so, during the school year, the Graveses were in Palma, and we’d regularly call in on them. I can remember having lunch in a special cafe; it’s so long ago that I can’t remember what decided whether we’d have lunch or tea or what. During the school year we’d see them once every three weeks in Palma, and then during the summer, when they were in Deià, we perhaps would only see them for Robert’s birthday party. You know, his birthday was a great event, and we actually walked over the hill. We did this ten kilometre walk, and then we’d spend the night in Deià with some friend or other after the party; and then we’d walk back the next day, and we might only see the Graveses on that one occasion during the summer holiday because, well, we couldn’t afford to take a taxi; and it was rather a long walk. And we lived there for four years, and so it was just our life and we didn’t feel any great urgency to hurry, to rush over and see him. But what I do remember is, Robert, if he was working, would sometimes invite me into his study and show me the poem that he was working on, and he’d explain what he was doing; and then it was the most fantastic education. I’m sure it was the equivalent of being with one’s tutor at Oxford or Cambridge. It was the best possible education about how to write poetry and how to be a poet.

CM: Did he explain what he was doing in a formal sense, or in terms of the development of the subject – or a complex mixture of the two?

RF: Well, I showed him very few poems of mine because I didn’t think they were good enough, you see, and I don’t think he had a very high opinion of my work at that time, if ever. And yet he did this wonderful thing for me.

CM: Yes. He seemed to get into difficult positions with respect to women poets, didn’t he?

RF: Yes, I think so.

CM: And I think probably had quite a complex set of well, prejudices, thoughts, intellectual positions around gender more generally, possibly even his own to a certain extent.

RF: Yes, well, I mean his Man Does Woman Is: I found that really infuriating.

CM: Absolutely the word for it, yes!

RF: Yes, I really liked him and I liked, I loved Beryl. (You know we went together to the USSR in 1965.) And they were just a very nice family to know, and I respected him as a very good poet and writer.

CM: Yes, luckily we are able to allow our friendships to develop regardless, sometimes, of those kinds of pronouncements.

RF Yes, that’s right.

CM: So he would talk you through the poems that he was working on. Did you in a sense then take what you were learning and apply that or incorporate it into your own practice of writing? Was it that sort of direct influence or was it just recognising that you know, here’s someone going about their work in a professional way and that you could learn from that? How directly was the line of influence?

RF: Direct enough, I think. He didn’t set me any tasks or exercises or ask me if I would show him what I was working on, to see if it had had any influence on me. But, I thought that he took me seriously enough to waste his time, or to spend his time, doing this for me. I mean, it was very affirmative that he did this: that he didn’t dismiss me. And because I was interested in, and moved by, classical mythological subjects, I felt there was an affinity between us.

CM: In terms of Alan’s work as well, there’s a sort of famous story that Graves said to Alan, well write about what you know, and that Saturday Night and Sunday Morning emerged. Is that true?

RF: It’s true in the sense that Alan had written a couple of fantasy novels and he’d also written some short stories which were fed straight into Saturday Night and Sunday Morning, which were based on his life in Nottingham; and Robert had said, ‘well, look this is what you should be doing. This is really what’s good, and the fantasy stuff is all very well but . . ..’ So that’s true, yes. I don’t know what their relationship was with regard to Alan’s poetry to tell you the truth, and I don’t know if . . . I mean, Alan and I didn’t discuss it with bated breath, we didn’t go home and say ‘ha! What did he say to you?’ ‘Ha! What did he say to you?’ No, it wasn’t like that.

CM: No it’s just life, isn’t it?

Alan Sillitoe and Ruth, Tokyo, 1980, photographer unknown FR: It was just life. So I don’t really know what went on between them, and I don’t know if I discussed this with Alan. I mean, he was perfectly aware that I would go into Robert’s room by invitation. I might well have said to Alan what Robert had said, but I might well not have. I can’t really remember.

CM: And so, Alan was writing poetry all through that period as well?

RF: Oh yes. I mean he did publish five or seven or however many collections of poems, and I think he was a very good poet. A great admirer of Alan’s poetry is Alan Jenkins, the poetry editor of the TLS. When I had a memorial service for Alan to commemorate the first anniversary of his death, Alan Jenkins was one of the people I asked to participate, and he read some poems of Alan’s, which he admired very much. But if people do something like write a novel, and then are called ‘the great proletarian novelist’ and so on and so forth, then no one takes much notice of the fact they write poetry as well.

CM: No, the novel is the genre that shouts the loudest. Not necessarily the longest, but the loudest.

RF: Yes.

CM: You’ve described some of the dynamic between you and Alan and the Graveses there, but I’m interested in a sense you must have been a group with quite different kinds of life experience, different ages, different temperaments and so on and so forth. Was that tangible or was it that you were in exile or poets in exile or just that there was a natural affinity between you and the Graveses?

RF: As I say, the fact that Robert Graves was on the island, and that he had lived there since before the Spanish Civil War in a completely different set-up with Laura Riding, was very important to me before going there – so I didn’t learn about it when I was there. I’m trying to remember how I learnt about it. I can’t really be more specific. Wasn’t I a clever little thing? [laughs] How did I come to know all this at such a tender age, not being educated, as it were?

CM: Well, you had a grammar school education and an art college education.

RF: Well, it was just one year at grammar school. Before that, I was at Washington Lee High School in Arlington, Virginia.

CM: Fantastic, and quite a culture shock, I should imagine, going into . . . and being a product of the Birmingham grammar school system myself: it’s quite a rigid affair.

CM: I didn’t know that you had any connection to Birmingham.

CM: Yes. I was at Bishop Vesey’s Grammar School

RF: This was King Edward’s?

CM: And you were at King Edward’s, yes?

RF: Camp Hill. That’s a suburb isn’t it: King Edward’s Grammar School for Girls Camp Hill. But as I say I was only there for a year and I wanted to go into the sixth form like my brother Harry. You know about Harry, I assume. I mean the rough structure of the story; that he was a poet and that he was mad in a sense, and that he died in his late forties . . .. Because we’d come from America it was just assumed that we were absolute dolts and so we were both put in the lowest stream. And we were both very good at school. We were very academic and so we just soared up and in the mocks I came top in English and History, and I was really pleased because I didn’t know any English History at all. I still don’t, actually – luckily we did the French Revolution. That was much easier than English History.

CM: And easier to understand from an American perspective as well!

RF: Absolutely, I mean the reason they cut the heads of aristocrats off is perfectly understandable to an American, but to keep having a Royal family century after century in England and worshipping them – that is very difficult to understand. [laughs]

CM: Good! Well I’m glad you brought your subversive United States citizen ways into the Birmingham grammar school system to shake it up a little bit.

RF: Yes that’s right. I don’t know; it must have been quite different, later, for you, but at the time we used to all meet in the Kardomah. That was the culture you know it was the place that the bohemians met. And Ken Tynan – have you heard of Ken Tynan?

CM: Yes!

RF: Well, he was our hero. He’d sashay in to the Kardomah and we’d see him: Kenneth Peacock Tynan! [laughs] Did you know that was his . . .?

CM: He was an unassuming character, was he, in real life?

RF: Very – most unassuming, yes. That was his actual name; I mean it couldn’t have been better.

CM: Some people are perhaps shaped by their names.

RF: That’s right.

CM: You mentioned that you would meet up at the summer festival of Robert’s birthday and so on, and he was renowned, I suppose, in Deià, for being a point for many artists and writers, a version of artistic Mecca, wasn’t it, in some respects?

RF: Oh yes, it was for that very reason we did not go to live in Deià, you see. I mean that was a conscious choice. You would never join the gang of groupies, you know, who were hovering around Robert. I mean, that was just absolutely not one’s style.

CM: No, certainly not. Did you meet other interesting writers, interesting artists during that period who were associating themselves with Robert, or again was it much more . . .?

RF: No, we met a few, yes, but not really the people who went to live in Deià. There were people who lived in Sóller and other villages around who we knew, yes, but no one of repute, except perhaps towards the end of our time there, when we met the Swedish actress Ulla Jacobsson and the Dutch painter Frank Lodeizen, a very likeable couple who had a house in the next village. Who was the man who was the tutor of the Graves Children?

CM: Bill –

RF: Merwin. Yes that’s right. I never met him. I don’t know if we overlapped or I think probably we didn’t overlap. I think he’d left already by the time we arrived.

CM: I’m not sure how long he was there. But, okay, to touch on your own poetry: are there any particular poems which you feel Robert has an influence on, either in terms of their subject or their voice? You obviously share interests in mythological subjects, but I sense that your interest in mythology is self-sustaining anyway. But is there anything in particular that you feel has something that it owes to Robert Graves?

RF: Yes, probably yes. Later, when we were back in London, I wrote a few poems that, when I sent them to Robert, he said, ‘I hope that’s not about me’.

CM: [laughs] And were there any that might have been?

RF: Yes. [pause]

CM: Any you’d be prepared to name at this juncture?

RF: No. I’d have to look first, you know.

CM: I just read a line there: ‘ageing means smiling at babies’ and it recalls to me Graves’s line about tickling babies, which is one of his war poems where he is describing the disjunction between experience of life at the front and experience of life just a few miles behind the front where there’s this sort of absolute semblance of normality and of life perpetuating itself: a quite extraordinarily horrifying and effective war poem. I was wondering about ‘Old Man in Love’, which is directly followed by ‘The Black Goddess’ poem; that seemed to me to be a sort of little Gravesian corner of your work; but maybe that’s me getting the wrong end of the stick.

RF: Well, you’re not far off. [reading] ‘The old bear’, yes. Oh yes: ‘Ageing means smiling at babies in their pushchair’. No, this is about Virginia Woolf or Algernon Swinburne. Anyway I was quite glad to get a rise out of Robert with those poems. [both laugh]

CM: Thinking about mythology, and clearly for Graves it was both a sort of liberating and enslaving element of his, of the life of his mind, in ways that we’ve already touched on in terms of his thinking about women and poetry in relation to the idea of the Muse and all that kind of stuff: your own poetry is drawing on mythological and the mythologically feminine in different but related ways. Do you find that?

RF: Different but related – you mean to his?

CM: Yes.

RF: Ok.

CM: Well, is that fair or . . .

RF: Fair enough.

CM: So there’s not a sense at any point in your career when you felt that what you’re doing is, if you like, a sort of useful corrective to some of the wrong turns taken in the thinking around the white goddess?

RF: Mm. There are such strange stories about the way Laura Riding treated Robert, you know; she just seemed to break his spirit; terrible. It’s rather unpleasant, the whole story. And whether – I don’t really know about Robert and mythology, and classical mythology pre-Laura, or apart from Laura. I understand Robert and his Celtic mythology, the white goddess and so forth. That’s his Welsh and German inheritance. But I have a feeling that the Mediterranean mythology . . . that she told him what to think almost. That might explain some of the more way-out theories in Greek Myths.

CM: That’s interesting. He did, I suppose, have the typical public school classical education.

RF: That’s what I was going to say. He did learn Latin and Greek, and so forth. How I longed to have learnt Latin and Greek, and I tried to teach them to myself, but it was impossible. I couldn’t. I’m hopeless at learning a script that isn’t the Roman script. You know, Hebrew, Arabic, Russian: I tried to learn languages with different scripts so often and I’ve never managed even to easily read the alphabet.

CM: No, I’m the same – well I did study Latin for a number of years at grammar school, but I never really got beyond struggling through the odd page of Ovid with a dictionary.

RF: I mean, Latin, I think that would have been ok, and I did teach myself some Latin because it’s the same alphabet. It’s not a different script like Greek. But with Greek, I couldn’t manage; and after all I’ve been in connection . . .. What I find very interesting is that I’ve been translated into every Latin language, every Romance language, you know, Spanish, Portuguese, French, Italian, Romanian: have I left any out?

CM: [laughs] That’s like a geography question!

RF: What I mean is, I’ve never been translated into any other language. I’ve never been translated into German or any Scandinavian language; and I find that interesting.

CM: Yes. And is that because of the sort of networks of people that you meet who are interested in your work, or . . .?

RF: Maybe. Quite a lot of poems have been translated into Russian as well, but I haven’t had a book. I’ve had a book in all those languages, but not in Russian. I’ve had a lot of poems in the best Russian literary magazines, but not an actual volume. I don’t appeal to the Scandinavians or to the Teutons, you see.

CM: You’re too hot-blooded?

RF: It’s nothing to do with that!

CM: You wonder to what extent it’s coincidence and to what extent it’s a matter of literary taste, of difference.

RF: Anyway just en passant it’s interesting.

CM: Yes. We’ve been talking for quite a while, but could I just ask you one last question about Robert? Obviously we’ve got 2016 coming up quite soon, and July, the Battle of the Somme. In 1916, he was left for dead and wrote that marvellous poem about going down to hell and fighting off Cerberus and actually making his way back up, coming back into being born a second time. And clearly war was a deeply traumatic and formative experience for him. Did he ever talk about it, or about the Second World War?

RF: He might have with Alan but not with me, no.

CM: It seems to me a great shame that one of the things that he did in editing his poetry over his lifetime was to effectively edit out his life as a war poet, and in doing so edited himself out of, if you like, in many respects, the canon of war poetry, in which I think he absolutely belongs.

RF: Yes, I think Michael Longley is doing good things, isn’t he, about that?

CM: Absolutely, very important work.

RF: I’m sure he and Alan must have talked about it because Alan was so interested in the subject, but I didn’t know enough and I wasn’t that interested; nor do I think Robert would have been comfortable talking about his war with me.

CM: Well thank you ever so much Ruth. This interview took place in the Department of Humanities at Sheffield Hallam University on 14 April 2015.

Charles Mundye is President of the Robert Graves Society and a Fellow of the English Association. His edition of Robert Graves's War Poems was published by Seren in 2016.