|

Search Help |

|

Links Robert Graves Website Other RG Resources |

Historical Trace

'What the Dickens?': The Real Man Behind the 'Fighter' in Good-bye to All That

During these centenary years of the First World War since 2014 I have been particularly interested in using an approach in my writing and broadcasting work which might be call ‘story-driven remembrance’ – finding a personality who has an interesting back story, researching that story and bringing them to life either on the page, over the airwaves or on screen, and then using that individual’s experience as a prism through which we can examine wider perspectives on the war.

Democratic

Robert Graves was, in my opinion, one of, if not the, first great exponent of story-driven remembrance of what was dubbed by the victors as the ‘Great War for Civilisation’. After all he started it almost 90 years ago with the publication of Good-bye to All That in 1929 and his many readers over many editions in the intervening years – including Fran Brearton’s timely ‘back to basics’ edition of 2014 – were aware of the stories he tells of ‘prominent personalities’ he featured in the book.

Yet Graves is nothing if not democratic – he allows us fleeting glimpses of other – some might say, lesser – characters, although that would not be a description Graves would ever have used, because it is clear from the way that he first introduces us to these people and how he then develops his recollections in his writing that he had huge admiration and respect for some of them.

Graves’s fleeting references to these people with fascinating ‘back stories’ – many of them soldiers he served with - are a tantalising prospect for me as a professional military historian. I thirst to know more but for all Graves’s democracy in including them we still know very little about his men.

I believe it is important to try and balance Graves’s ‘narrative’ by populating the ‘hinterland’ of Good-bye to All That through research on what I will call his ‘Mechanicals’; the rank and file soldiery of the Royal Welsh Fusiliers, many of them skilled in the art or craft of war and acting out their own subplot in Graves’s greater narrative arc. Some of these men are – to paraphrase the actor and director Simon Callow, who recently wrote about Shakespeare’s Mechanicals for the British Library – often ‘witty’ and sometimes ‘feisty’, ‘despite having the potential to turn into a mob’.

I have been looking at some of the 'rank and file' referenced by Graves and will focus here on one man whom I believe Graves respected hugely – after re-introducing another.

Tottie Fay

5307 Sergeant Charles Dickens – he really couldn’t have had a better name could he – of First Battalion the Royal Welsh Fusiliers (1/RWF) is first introduced on pp. 225-27 of the third impression of the 1929 edition – in fact he appears only two paragraphs after what must be one of the most oft-quoted lines in the book when Graves first meets Siegfried Sassoon after Graves is transferred to First Battalion – then reorganising after the heavy Loos fighting – in November 1915 and Sassoon shows him some of his poems:

‘This’, remarked Graves drily, ‘was before Siegfried had been in the trenches. I told him, in my old-soldier manner, that he would soon change his style’.

You may remember that Graves was allowed to take his servant, Private Fahy – ‘known as Tottie Fay, after the actress’ with him when he transferred. Fahy ‘worked well’, said Graves, ‘and we liked each other’.

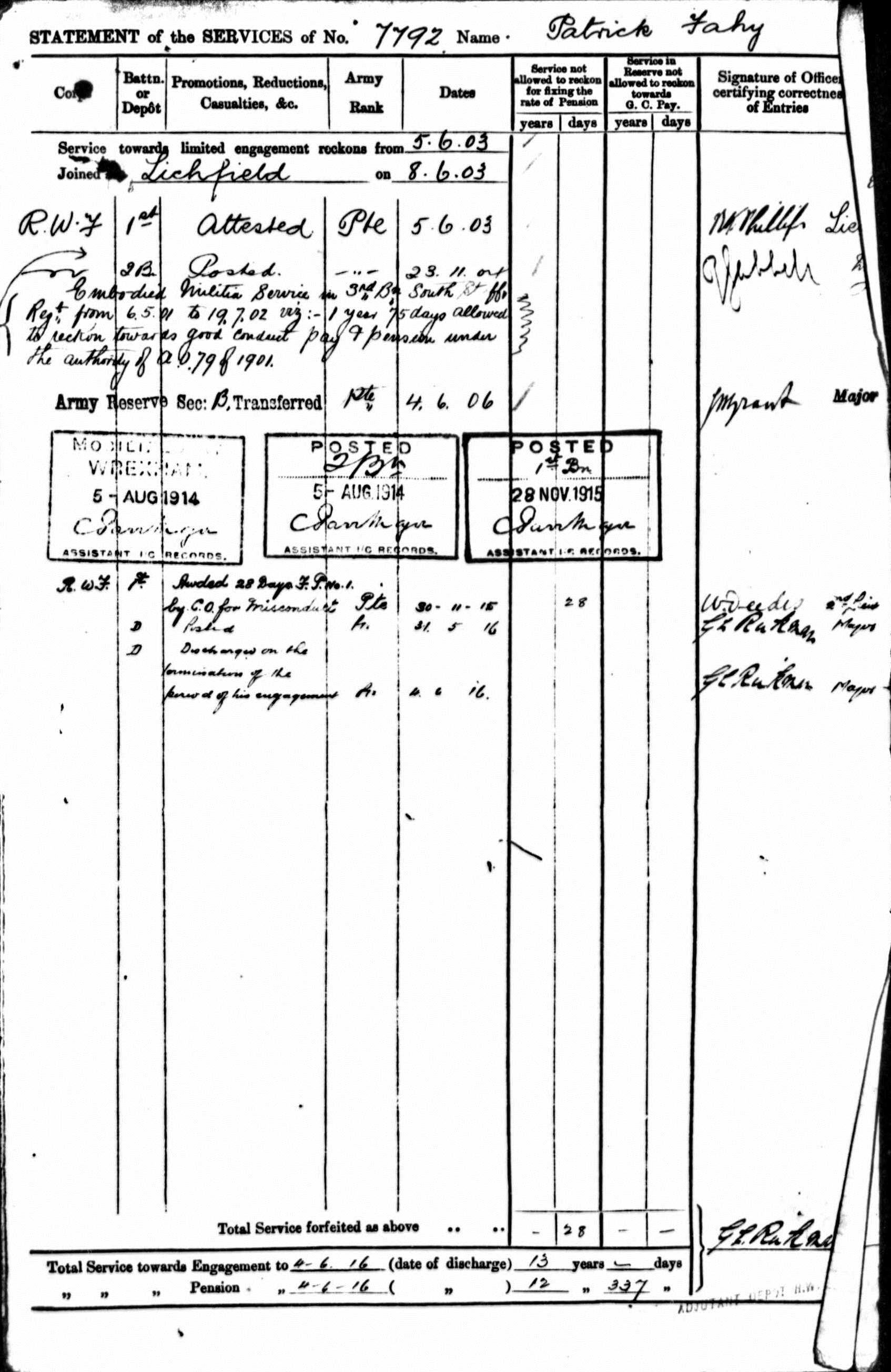

Part of Patrick 'Tottie' Fahy's Service Record. Soldiers’ Pension Records, The National Archives WO364/1167

Tottie Fay was in fact 33 year-old Patrick Fahy. Born in Walsall Staffordshire, on the date of his transfer to 1/RWF, Fahy was a married man – to Gertrude – with three children under the age of 6: Albert (5) Dora (2) and Olive, one day short of her first birthday.

Tottie had served in the Second Anglo-Boer War with the South Staffordshire Regiment and was still serving in the Third Militia Battalion of the South Staffs when he joined the RWF in June 1903 for a stint of three years with the Colours and nine on the Reserve. So when war was declared on 4 August 1914 he was called up the next day – leaving Gertrude (six months pregnant) to bring up two small children with the help of her parents.

Fahy was in France three weeks later. So Graves’s servant was able to call himself an ‘Old Contemptible’.

Field Punishment No. 1

Graves tells us that when he and Fahy switched battalions Fahy bumped into an old pre-war ‘boozing chum’ from the time he had been stationed in India ‘seven or eight years back’. This was Sergeant Charles Dickens. The celebrations which accompanied the rekindling of this old friendship had irritating consequences for Graves who was annoyed when he woke next morning to find his buttons were ‘not polished’ and that he had no ‘hot water for shaving’, which made him late for breakfast. But the consequences for Tottie were far more serious as recounted by Graves:

‘On my way to rifle inspection at nine o’clock . . . I noticed something unusual at the corner of the farm-yard. It was Field Punishment No. 1 being carried out – my first sight of it. Tottie was the victim. He had been awarded twenty-eight days for drunkenness in the field’. He was spread-eagled to the wheel of a company limber, tied by the ankles and wrists in the form of an X. He remained in this position – ‘Crucifixion’ they called it – for several hours a day… I shall never forget the look that Tottie gave me. He was a quiet, respectful, devoted servant, and he wanted to tell me that he was very sorry for having let me down. His immediate action was an attempt to salute; I could see him trying to lift his hand…but he could do nothing; his eyes filled with tears…I told Tottie that I was sorry to see him in trouble. Some time in the summer of the following year his seven years’ contract as a reservist expired. [Fahy was sent home and] made a starred man…so important to industry…that he could not be spared for [further] military service, so Tottie is, I hope, still alive.’

Graves’s account can be corroborated using Fahy’s statement of service file in which is recorded:

1. Fahy’s exact date of posting/transfer to 1/RWF - 28 November 1915

2. The date of the commission of his crime and the military reason – 30 November 1915 – ‘misconduct’ and

3. The date when he was posted to England – 31 May 1916 – and discharged ‘D’ – 4 June 1916

Fahy’s period of engagement should have expired in June 1915 but his terms were to serve an extra period not exceeding a year during time of national emergency – hence his actual discharge in June 1916.

Charles Dickens

Graves tells us the story of Tottie Fay in order to introduce us to Sergeant Charles Dickens – the man with whom Tottie got blind drunk and the contrast with Graves’s ‘quiet, respectful, devoted’ and tearful servant could not be more marked.

‘Sergeant Dickens was a different case. He was a fighter, and one of the best NCOs in either battalion of the regiment. He had been awarded the DCM and Bar, the Military Medal and the French Médaille Militaire. Two or three times already he had been promoted to sergeant’s rank and each time had been reduced for drunkenness. He escaped field punishment because it was considered sufficient for him to lose his stripes, and whenever there was a battle Dickens would distinguish himself so conspicuously as a leader that he would be given his stripes back again.’

Yet Graves’s short, succinct appraisal doesn’t even begin to scratch the surface of the man. Dickens was a real, obviously pugnacious, and larger than life character who – no doubt about it – had seen it all and had done much more during what had been (by late 1915) the best part of 20 years of full and part-time soldiering.

So, who was the man Robert Graves knew as ‘Charles Dickens’?

Soldier of the Queen

First he was not Charles Dickens – ‘ENS’ – at all. He was born Charles E Dickin – ‘IN’ – the son of Frederick and Rhoda Dickin in Rhosddu, now a suburb of Wrexham, Denbighshire in 1880.

According to the Welsh Census of 1891 Charles – an eleven-year old schoolboy – was living with his family in Marchwiel, a village some two miles southeast of Wrexham.

We have no record of exactly what Charles was up to between 1891 and 1897 but from an army document dated August 1897, which records information on a man on transfer from the Militia to the Regular Army – we know that 2196 Charles Dickens – aged seventeen and one half – had enlisted in what was then the 3rd Battalion (Militia) of the RWF in that year. Another document records that he was employed as a labourer. The documents also record the variation of the spelling of his surname. As far as the army were concerned he was now Charles ‘Dickens’ – ENS; and that was the way he would stay!

Prior to Lord Haldane’s Army Reforms of 1908, which resulted in the creation of the part-time Territorial Force primarily for Home Defence, Britain had relied on a long tradition of organising locally raised part-time military units – known as the Militia and the Volunteers – for home defence in times of national crisis or emergency. It was such a unit that the young Charles Dickens had joined.

Dickens’s army number – 2196 – is compatible with the date range for the Third Battalion Militia regimental numbers pre-1908 and we know we have the right man because a hand-written addition – ‘WF 5037’ – in the top left corner became Dickens’s RWF regular army regimental number prior to the one he acquired during the First World War.

And it is from that document that we get our first glimpse of Charles Dickens the young soldier:

Height: 5 ft. 3 2/8 in.

Chest: 32 ½ in.

Fresh complexion

Grey eyes

Sandy hair

Tattoos: ‘head and figure also CED on rt. forearm. CD

and indefinite left forearm’

On 28 July 1897 Dickens had enlisted in the regular army on standard terms - seven years with the Colours and five on the Reserve. He stated that he was already serving with the 3rd Battalion at the time – the 'militia' as he called it.

On attestation his physical description was as follows:

Height: 5 ft 3 in.

Weight: 117 lb – i.e. 8 stone, 3 lb!

Tattoos: ‘Figure of woman, head of man and CED –

r forearm. Figure of woman and cross within circle left forearm’

Chest: min 33 in. - max 35 in.

South African Service

Dickens was posted to 1/RWF on 7 January 1898 and served in the British Isles until 22 October 1899 – eleven days after the start of the Second Anglo-Boer War – when he sailed for South Africa with 1/RWF aboard the SS Oriental. He wouldn’t see his native country for another three years and 105 days.

He arrived at the Cape about 13 November 1899 and 1/RWF were sent to Durban where it formed part of the 6th Brigade under Major General Barton, along with the Second Royal Fusiliers, Second Royal Scots Fusiliers and Second Royal Irish Fusiliers.

There is not space here for a detailed analysis of the battalion’s actions in South Africa but from the battalion record and Dickens’s medal entitlement there can be no doubt that Dickens saw some sharp action.

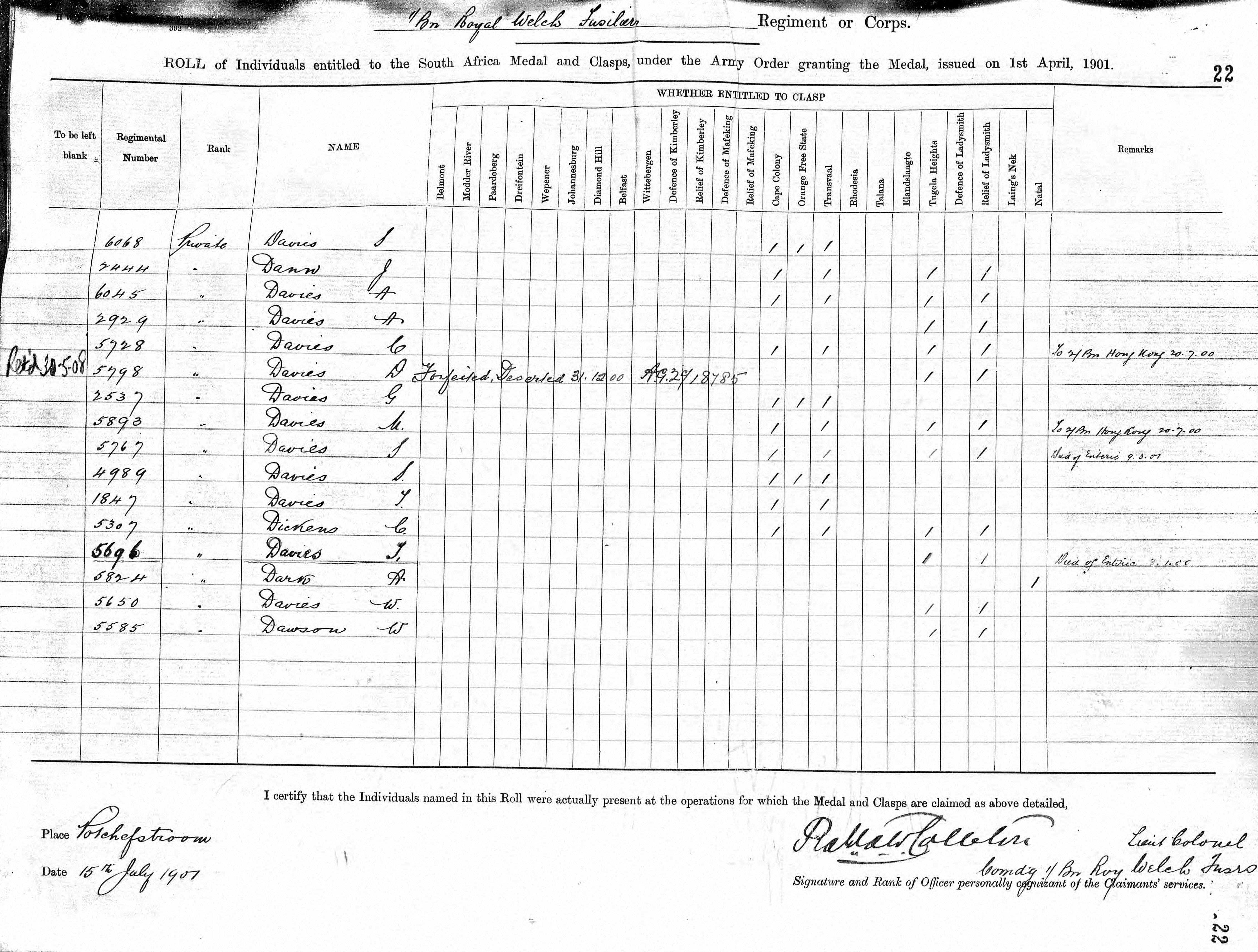

Charles Dickens’s name, fifth from bottom, on the Queen's South Africa Medal Roll showing his entitlement to specific clasps. The National Archives, WO109/181

The RWF South African (SA) medal rolls record that he was entitled to receive both the Queen’s and King’s SA medal; the former with five clasps: ‘Cape Colony’, ‘Transvaal’, ‘Tugela Heights’, ‘Relief of Ladysmith’, ‘Orange Free State’ and the latter with the two date clasps ‘1901’ and ‘1902’.

He had just emerged from five days ‘confined to barracks’ at Chieveley Station – about one hundred miles northeast of Durban in what is now Kwa Zula Natal – for being ‘absent from parade with the defaulters from 5.30 a.m. until 7.30 a.m.’ when his battalion set out to take part in the series of actions which collectively went under the name of The Battle of the Tugela Heights – 14-27 February 1900.

The 1/RWF played its part throughout the fourteen days of hard fighting which followed. On 24 February the RWF were holding several kopjes, including Railway Hill, under very heavy shell and rifle-fire and on that day Dickens lost his CO, Colonel Thorold, killed in action. Another officer, and six men were killed and two officers and twenty-nine men were wounded.

In the fourteen days of the battle the battalion's total casualties were some two officers and eight men killed, two officers and sixty men wounded.

In April 1900 the 6th Brigade was posted to Cape Colony and concentrated at Kimberley. On 5 May the Battle of Rooidam was fought, the RWF and the Royal Fusiliers being in the front line. For their work in the very arduous pursuit of Boer general Christian De Wet in August 1900, the RWF were highly praised by Lord Methuen.

At Frederickstad between 15 and 25 October 1900 the 6th Brigade was again involved in severe fighting and the RWF lost some fifteen men killed and three officers and thirty men wounded.

During 1901 the battalion remained in the Western Transvaal and took part in the very successful operations of General Babington.

Dickens was also severely wounded and taken prisoner and released near Paardeberg all on the same day – 29 April 1901 – but sadly we have no further details. We do know however, that the Boers could not afford to keep prisoners after capture, having no means or resources to hold and feed them. The fast moving Boer Kommandos on horseback could not risk being hampered by lumbering British PoWs on foot. So British prisoners were relieved of their boots – a terrible impediment on the South African Veld – their rifles, ammunition and often their trousers as it was the one item of British kit the Boers could wear without being mistaken for ‘Brits’ and risking a ‘blue on blue’ incident.

It was also thought that capturing and then releasing British prisoners quickly impacted negatively on the British soldier’s performance in battle as it encouraged swift surrender; the choice between enduring accurate Boer Mauser fire and surrendering quickly and safely must have been very attractive. Boer general Marnie Maritz once complained that he captured the same British soldier three times in one day and had to let him go each time. However, Maritz noted that his Kommandos profited from each capture since the British soldier was fully outfitted every time they caught him.

Towards the end of 1901 1/RWF occupied the northern portion of the line of blockhouses running from Potchefstroom to the Kroonstad district.

Discipline

It might be appropriate at this point to touch on Charles Dickens’s disciplinary record – his accumulated charge sheets running to over thirty pages.

Space dictates that we cannot cover all Dickens’s offences here – we would need an entire issue dedicated to them – so we will have to settle for edited highlights!

It is a litany of crimes – some minor, some moderate and some of a more serious nature – committed with high frequency and recorded in both the Company Defaulter Book for crimes handled at company level and the Regimental Defaulter Sheets for more serious transgressions.

His very first offence at company level – ‘absent from kit inspection’ on 19 November 1897 at Wrexham – earned him three days Confined to Barracks (CB) and it all went quickly went downhill from there. His first regimental level offence – ‘using obscene language to a non-commissioned officer’ – was committed on 1 March 1898 while stationed at Fort Tregantle, one of several forts near Plymouth. He was imprisoned for forty-eight hours with hard labour. But there’s more: absent from tattoo, not complying with orders, entering public houses at night when on duty, improper conduct – arresting a married woman passing through Lichfield Barracks at about 9.00 p.m. on 14 November 1903 (eight days CB), absence from parade until apprehended by garrison police, creating a disturbance in barracks, found in bed at Reveille, breaking out of barracks when a prisoner, telling a lie, dirty on parade, disobeying an order – (found in railway station urinal!), improper language to a patient under observation, striking a comrade, resisting escort, drunk. And on and on and on! ‘Recidivist’ is an entirely appropriate label in this case.

After so many offences stretching back to that first brush with imprisonment in 1898 it was while he was serving in SA that Dickens felt the full force of military law when he was tried by several Courts Martial:

17 March 1902: Tried by Field General Court Martial whilst on ‘line of march’ for the crime of ‘when on active service using threatening language to his superior officer’. Sentenced to forty-two days imprisonment with hard labour.

3 November 1902: Tried by a District Court Martial in Kimberley for the crime of ‘striking his superior officer’ – a crime which could result in a death sentence on active service during the First World War. Found guilty and sentenced to six calendar months ‘imprisonment with hard labour’.

Soldier from the war returning

Dickens and his battalion returned to Britain in March 1903 and he extended his service to complete eight years on 5 April 1904 at Lichfield – the descriptive return on signing for the extra year was that he was a ‘Good Soldier’.

He was transferred to the Army Reserve Section B on 27 July 1905 at the end of his service with the Colours. A year later – on 9 July 1906 – he married Elizabeth McCann at St Mary’s RC Church in Wrexham. The male witness was one Ernest Parry – I guess that after so many years’ service ‘Parry’ must have been a soldier but the odds of finding the right ‘Parry’ in a Welsh regiment are only marginally better than finding the right Jones! There are several contenders but I cannot be certain of any of them.

And his troubled relationship with the law continued. A document from HM Prison Shrewsbury in Dickens’s papers – ‘the conviction of a soldier … now confined in the above named prison under sentence imposed by a court other than a military court’ – reveals that life had its ups and downs whilst he was still on the army reserve, although effectively working as a labourer on ‘civvy street’.

On 1 July 1908 he was arrested In Wrexham for common assault – a misdemeanour – and convicted five days later. He was sentenced to either seven days hard labour or a fine of ‘22/-10’ – a fine equivalent to just short of £1.15 in today’s currency. It appears that after doing the crime, he served the time. The experience would not have come as a surprise of course. After all it was not the first occasion he had been ‘in clink’.

Dickens was discharged from Section B Army Reserve on 27 July 1909. His Regular Army twelve year terms of engagement – that is his eight years in the colours (expired 27 July 1905) and four years in Section B of the Army Reserve had finished.

It is interesting to note the record of his conduct and character on discharge: ‘Indifferent, has been guilty of frequent acts of absence’, however, an addition appeared later ‘but is most willing and hardworking’. Was this the work of a kindly officer wanting to lend a helping hand to a veteran soldier seeking future employment?

The entry under the column ‘Number of Good Conduct badges’ is revealing – the figure is not difficult to guess – ‘nil’.

At this point Charles Dickens had served in the RWF for twelve years of which seven years 141 days counted towards an army pension.

Reservist

In late January 1910 Dickens – now aged almost thirty-one – was living at 5, Albert Court, Beast Market in Wrexham and working as a labourer.

On 26 January 1910 he re-enlisted in Wrexham for a further period – General Service, Infantry – in Section D of the Army Reserve of the RWF. Section D Reserve was for men who had completed their time in Section B Reserve and chose to extend their time on the reserve for another four years.

He was now liable to four years’ service and could only be called upon ‘during time of imminent national danger or great emergency’ and for an additional period ‘not exceeding twelve months if so directed by the competent military authority’. His reserve pay was in the order of 3s. 6d. a week to augment any civilian income from his labouring.

He was now thirteen years older than the day he had enlisted but his body had changed considerably. Picture now the somatotype of this thirty year old as we study his vital statistics:

He was taller at 5 ft 7 in.

Chest measurement now 40 in.

Waist measurement now 35 in.

Helmet size: 21 ½ in.

Size 7 boots

A typical mesomorph – built like the English Rugby Union hookers of my youth – for older rugby fans think Brian Moore. Short, squat, stocky, powerful . . . almost square!

War with Germany

With his discharge from the Army Reserve on 25 January 1914 – just less than seven months prior to outbreak of war – this is unfortunately where Dickens’s service record runs dry. We can only piece together his First World War service with snapshots from other sources.

We do not know exactly when Charles Dickens joined 1/RWF again but we have heard from Graves that he was in France when he and ‘Tottie’ Fahy joined 1/RWF in November 1915.

In fact we know from other sources that he must have enlisted very early in the war as his Medal Index Card shows that he landed in France on 23 November 1914 – just one too day late to qualify for the 1914 Star – 5 August to midnight 22/23 November 1914 being the qualifying dates for that medal. He received the 1914-15 Star instead. Unlike his friend Tottie Fahy then, Dickens was not an ‘Old Contemptible’.

Although the information on him for this period is sparse, sources from the National Archives and the London Gazette point to a war record in which Dickens clearly displayed devotion to duty, distinguished service and gallantry. He was ‘Mentioned’ in Sir John French’s Despatch of 15 October 1915 covering operations between 15 June and 15 October 1915.

Graves remembers Dickens having been awarded the French Médaille Militaire but he is mistaken. In fact Dickens received the Croix de Guerre in February 1916. He kept good company. In the same edition of the London Gazette in which Dickens’s award is notified the names of Sir John French – Dickens’s first Commander-in-Chief - and Lieutenant General Sir William Birdwood appear. Dickens would have enjoyed that.

On 16 August 1917 Dickens was officially awarded the Distinguished Conduct Medal, which was viewed then as the second highest award for gallantry in action after the Victoria Cross for all ranks below that of commissioned officers. His citation reads:

‘For conspicuous gallantry and devotion. Although badly wounded, he collected some men, after the failure of an attack, dug a strong point, and held on all day, resisting two heavy attacks.’

Sergeant Charles Dickens's Distinguished Conduct Medal Citation as it appeared in the London Gazette in August 1917

A backwards trawl through the war diaries of 1/RWF from the date on which the notice appeared in the London Gazette has so far failed to reveal clues as to when and where his act of gallantry took place. My guess is that it occurred during the desperate actions around Bullecourt in the early summer of 1917, but there is more to be done on this. In his pen portrait of Dickens, Graves specifically mentions a Bar to the DCM – a second award – but there is no record of it, either during the Boer War or the First World War. There is no record either of the Military Medal to which Graves refers. Was this embellishment for impact and effect?

Scrapper

Dickens had undoubtedly seen what Wilfred Owen, in his masterful poem ‘The Chances’, would later refer to in the vernacular of the time as ‘some scrappin’. He had certainly been in many scrapes and, as we have seen, not just on the battlefield; common assault, obscene language, drunkenness, striking superior officers, two courts martials and the acquisition and diagnosis of at least two ‘exotic’ sexually transmitted infections which required hospitalisation were just some of the entries which expended pots of regimental ink in his records. In total Dickens spent just shy of a year of his army career prior to the First World War imprisoned with hard labour and a staggering 302 days confined to barracks, and that was just his pre-war record. I wouldn’t bet my pension on his 1914 to 1918 record being spotless.

In fact we know it wasn’t because Graves tells us so and what matter if it is slightly embroidered. We now know enough of Dickens and his service to know that Graves might not have wandered too far from the truth for one final insight into the personality of Charles Dickens the soldier and the man from the pages of Good-bye to All That. As Graves watched, a draft of men – bound for the 1st Battalion on the Western Front – gathered to hear a speech from their commanding officer at Litherland station near Liverpool in the late summer of 1917:

When [the CO] had finished I went over and greeted a few old friends: seventy-nine Davies, thirty-three Williams, and the Davies who was nicknamed ‘Dym’ Bacon . . .. There was another well-remembered First Battalion man – DCM and rosette, Médaille Militaire, Military Medal, no stripe. ‘Lost them again, sergeant?’ I asked. He grinned: ‘Easy come, easy go, sir.’ Then the train came in and I put my hand out with ‘Good luck!’ ‘You’ll excuse us, sir,’ he said. The draft shouted with laughter and I saw why my hand had not been wrung, and also why the cheers had been so ironically vigorous. They were all in handcuffs. They had been detailed a fortnight before for a draft to Mesopotamia; but they wanted to go back to the First Battalion, so they overstayed their leave. The colonel, not understanding, put

them into the guardroom to make sure of them for the next draft. So they were now going back in handcuffs under an escort of military police to the battalion of their choice. (p. 329)

If true, my money would be on ‘old sweat’ Dickens being one of the ringleaders!

And in true storybook fashion, Charles Dickens survived. Discharged in 1919, he and his wife Liza had a child, Alfred Owen Dickens, born the same year. Alfred Dickens married Alice Bates in 1947 and they had one child, name unknown at present, who also had a child – again name unknown – whom I believe is still alive.

Respect

Despite his sorry disciplinary record Graves knew that Dickens, and men like him, were the ‘salt of the earth’. They represented the rank and file grumblers, the grousers and the scrappers of the old British Army. These men who had first enlisted as teenage ‘Soldiers of the Queen’ were the last remnants of that hard marching, hard fighting, hard drinking no-nonsense, no airs and graces army which Graves so admired. Dickens was undoubtedly a rogue but he and men like him were the very men Graves knew he had needed next to him when he had been at the sharp end of the fighting. He knew they were the men who – when down to your last few rounds and cowering from the flailing machine-gun bullets and cracking shrapnel in some half-flooded and God-forsaken ditch just taken at enormous cost and digging furiously to throw up some kind of parapet, even as the inevitable German counter attack came in . . . be it Loos or Festubert in ‘15, near Guillemont on the Somme in ‘16, or at Bullecourt or Passchendaele in ‘17.

Men like Dickens took it on the chin – probably quite literally in Dickens’s case – they stuck it, and ‘cracked on’. Put simply they endured. Graves knew it and he respected them for it.

Acknowledgements: With thanks to David Langley for his observations during the author’s very early research into Charles Dickens’s service life.

Jon Cooksey is a military historian who takes a special interest in the history of the World Wars and the Falklands War.

NOTES