|

Search Help |

|

Links Robert Graves Website Other RG Resources |

Historical Trace

Goodbye-Bye to All That: Mummy's Bedtime Story Book?

In their three full-scale biographies of Robert Graves, all of them exhaustively researched and all excellent in their own way, Martin Seymour-Smith, Miranda Seymour and Richard Perceval Graves devote significant space to Graves’s relationship with Siegfried Sassoon. They trace its origins in World War One France, the threat offered to it, first by Graves’s marriage to Nancy Nicholson in 1918, then more seriously by his affair with the American poet Laura Riding in 1926 and finally Sassoon’s stormy ending of their friendship after the publication of Good-bye to All That in 1929. All three describe in some detail Edmund Blunden’s review copy of Graves’s memoir heavily annotated by both Sassoon and Blunden, over 5,630 words on 250 of the book’s 448 pages, which Blunden has caustically sub-titled ‘Clarice, or, the Welsh-Irish Bull in a China Shop’. This copy has been available to scholars in the Berg Collection of the New York Public Library for many years, enabling me to consult it as early as 1991 in preparation for the first volume of my biography of Sassoon.

What none of us had then seen was Sassoon’s own copy of Good-bye to All That, noted by Graves’s first bibliographer, F. H. Higginson, but in private hands. It had been sent to Sassoon by the book’s unwitting publisher, Jonathan Cape, in the hope of advance publicity. Far from the glowing endorsement Cape hoped for from Graves’s well-known friend, Sassoon’s response was to threaten an injunction only six days before publication, unless two significant passages were cancelled. At the same time, Sassoon annotated his copy independently and, if possible, even more scathingly than he had Blunden’s. It lay buried in his library until 2007, when it was sold to a private collector. But it was not until it was sold again recently to the Beinecke Library (Yale University) that it became possible to view it. To do so was to realize that it changes the landscape of Graves|Sassoon studies significantly.

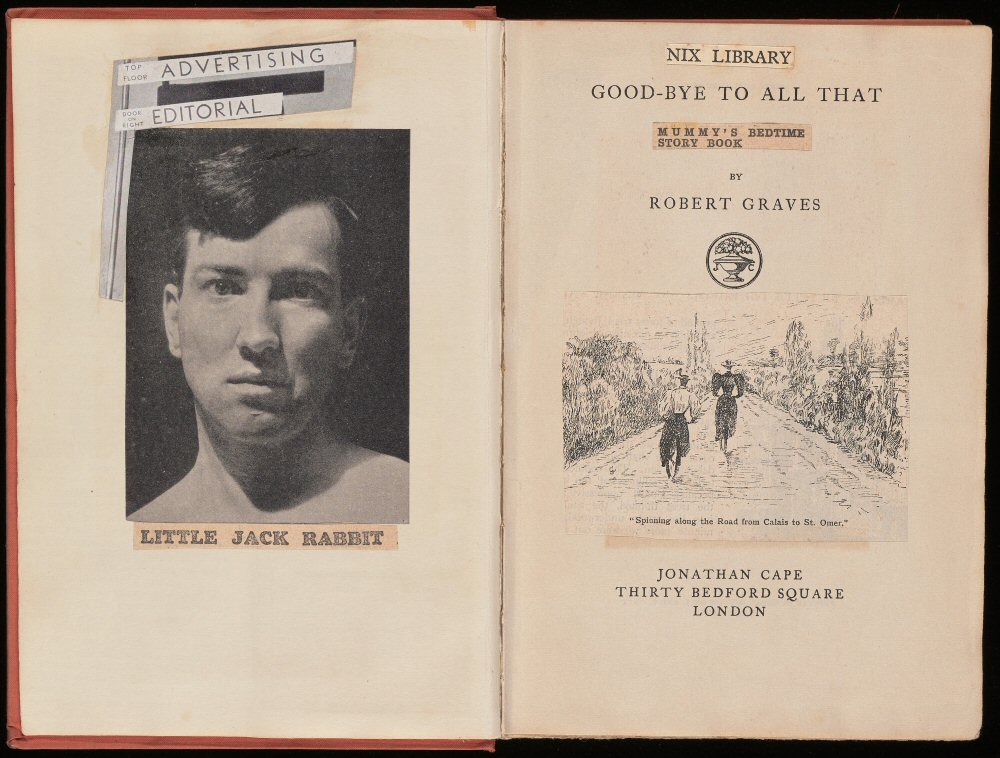

Title-page opening annotated by Siegfried Sassoon. The James Marshall and Marie-Louise Osborn Collection, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University

Good-bye to All That was by no means the first book to describe experiences in the First World War. As early as 1916 Henri Barbusse had published his graphic account of his time in the French army, Le Feu, and that same year Graves himself had started a novel on a similar subject, subsequently recycled in part in Good-bye. Shortly afterwards, in 1917 came a book by Graves’s fellow-officer in the Royal Welch Fusiliers, Bernard Adams, Nothing of Importance. It was the start of a flood of prose war-books which continued throughout the twenties and peaked in 1928 with Erich Remarque’s All Quiet on the Western Front, Sassoon’s Memoirs of a Fox-Hunting Man and Blunden’s Undertones of War. Having abandoned his novel of war-experiences shortly after starting it, Graves had no intention of swelling the numbers with his own contribution – initially, that is. For in 1928 Graves was still basking in the financial and critical success of his account of (T.E.) Lawrence and the Arabs published in 1927, and the acclaim for his collaboration with Laura Riding, A Survey of Modernist Poetry the same year.

But Graves’s need for still more money, to pay for Laura’s extensive hospital treatment after her dramatic suicide bid in May 1929 and, before that, his agreement to write an Introduction to yet another war memoir, American this time – E.E. Cummings’s The Enormous Room – evidently encouraged him to consider adding his own version of events. Cummings’s book had been brought to his attention, after it was published originally in America in 1922, by T.E. Lawrence, who urged Graves to find an English publisher for it where he had failed. Graves persuaded Cape to bring out an English edition and by 1928 had started on his Introduction. In it he would include two of his own army experiences, both of which would subsequently be included in Good-bye. The style and approach of Good-bye when it followed a year later, would certainly be nearer to Cummings’s directness, sardonic humour and lack of reverence for authority than to Sassoon’s and Blunden’s more circumspect narratives. It was, Graves admitted to Gertrude Stein in June 1929, a ‘quite ruthless’ book, though written ‘without indignation’.

The ‘indignation’ was all on Blunden and Sassoon’s side, particularly at Graves’s cavalier attitude towards so-called ‘facts’, adding to their already-existing grievances against him. Graves had antagonized Blunden earlier by implying that he had alcoholic tendencies, by his typically clumsy attempts to resolve Blunden’s marital problems and by an unsympathetic review of Undertones of War in December 1928. (Blunden would retaliate with a damning review of Good-bye in Time and Tide a year later.) Sassoon’s grievances against Graves were even stronger. Quite apart from his intense dislike of Riding, he felt that Graves had behaved badly towards his old friends, Edmund Gosse and Thomas Hardy. In addition, he had a particular dislike of factually vague war-books, as his dismissal of All Quiet on the Western Front had shown. Partly because he and Graves had been such close friends during the war, when he had visited the Graves family in Wales and Robert had returned with him to Sassoon’s family home in Kent, he reacted violently to what he saw as Graves’s betrayal of trust in describing this Kent visit in Good-bye. Mrs Sassoon was still grieving the death of her youngest son, Hamo, (a casualty of Gallipoli) and Graves referred to her desperate attempts to contact her son though spiritualism. Although the account names no names, Siegfried was appalled.

He also objected strongly to Graves’s unauthorized inclusion of a long, disturbed verse letter Sassoon had sent him from hospital in July 1918 while recovering from a head wound. Good-bye, he told Graves, could not have appeared at a worse moment, as he struggled ‘to recover the essentials of [his] war experience’ for Memoirs of an Infantry Officer; the book ‘landed on [his] little edifice like a Zeppelin bomb’. Elsewhere he noted that he felt as if Graves had ‘rushed into the room and kicked [his] writing table over, thrown open all the windows, let in a big draught’. It seemed to him that Graves had ‘blurted out [his] hasty version’ like a hack journalist with scant regard for accuracy, the ‘antithesis’ of his own method. He was particularly critical of Graves’s account of his (Sassoon’s) protest, which fell a long way short, he believed of the ‘impartial exactitude required for such a sensitive topic’. ‘He exhibits me as a sort of half-witted idealist’, he complained to Louis Untermeyer and his wife, 'with a bomb in one hand and a Daily Herald in the other’.

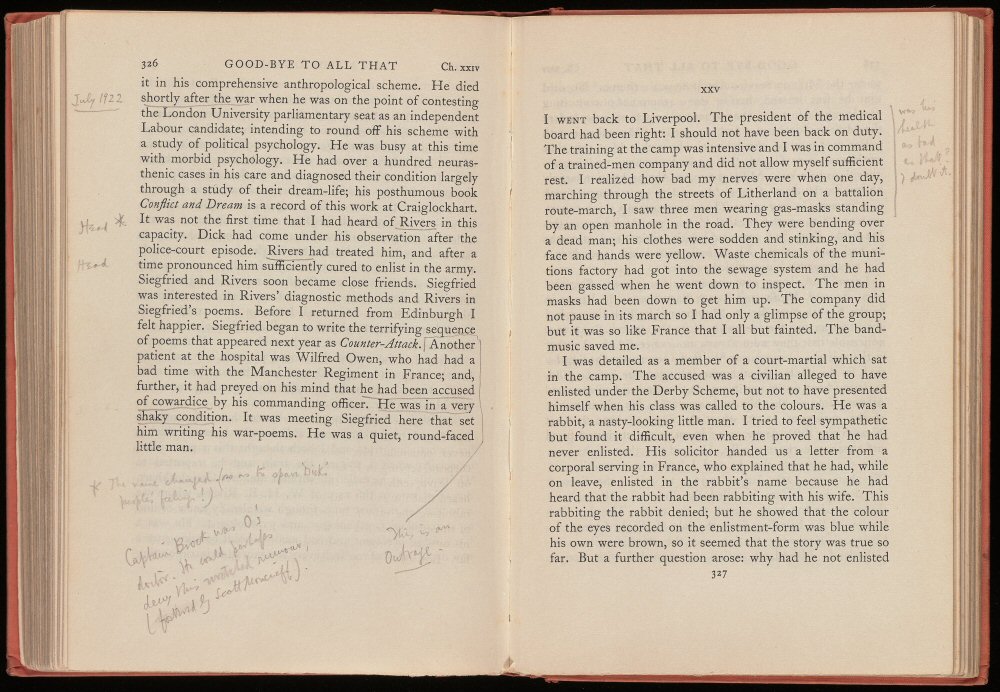

So Sassoon readily agreed to Blunden’s suggestion that they should do a ‘demolition job’ on the book and place it in the British Museum, ‘to preserve the correct version of what happened in France’. More than half the annotations were by Blunden, who began by noting on the first page that Graves’s specified ‘objects’ in writing were ‘all selfish’. This still left Sassoon ample room to add his own comments, but it was clearly not enough to satisfy him. His need to annotate his own copy shows just how obsessional he had become on the subject. He remained sufficiently aggrieved to make copious comments on a further 85 pages of his personal copy, continuing to correct the factual errors which had so enraged him when he first read Blunden’s copy. Some of these are significant. When in chapter 15, for instance, Graves claims that a colonel with ‘a slight wound’ on his hand ‘joined the stream of wounded and was carried to the base with it’, Sassoon appears fully justified in commenting: ‘a libel, he was hit on the head as well’. But on the whole the effect of this constant factual correction is to make Sassoon seem pedantic and petty. Are most readers really going to care if Graves dates his Quartermaster, Joe Cottrill’s award of the D.S.O. as 1916 rather than 1917, or if there are slight inaccuracies of transcription in an extract from the poet John Skelton?

If Sassoon had limited himself to correcting Graves’s ‘facts’, this second copy would add little to what we learn from Blunden’s. But in his own private copy Sassoon reveals far more of his changed feelings towards his former friend, and more freely. Some annotations consist simply of a scornful, single word, such as ‘rot’, ‘fiction’, ‘faked’ or ‘skite’. Others are more discursive. When Graves notes on page 440 that Bernard Shaw had ‘mistaken me for my Daily Mail brother’ (Charles Graves wrote a column for that popular tabloid), Sassoon observes ‘a pardonable error’. And when Graves tells his reader on the next page: ‘My critical writings I did not tidy up; but let them go out of print’, Sassoon adds, with what sounds like professional jealousy: ’they were mostly remaindered, and no new editions could possibly have been called for’. What Sassoon had once found forgivable, even endearing faults in Graves – ‘his tactlessness, his intelligence, and dirty habits’ – now irritate him greatly. So that, when Graves writes that the Prince of Wales was ‘a familiar figure in Bethune. I only spoke to him once; it was in the public bath, where he and I were the only bathers one morning’, Sassoon cannot resist underlining ‘the public bath’, with the gloss ‘rarely visited by the author’. The effect again is to make Sassoon seem rather petty.

The James Marshall and Marie-Louise Osborn Collection, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University

The real interest of this second annotated copy, and its main difference from Blunden's, lies in the 40 pages of press-cuttings Sassoon has added, most pasted down, a few inserted loosely into the text. Not only do these give further insights into Sassoon's character, particularly his often whimsical sense of humour, and allow us a late glimpse of the satirist who had dominated his war poetry and verse collections of the twenties, but they also turn his effort into a minor work of art. (He would do something similar with Edith Sitwell's Aspects of Modern Poetry [1933] once their friendship had cooled.) Coming from a family of painters and sculptors on his mother’s side, he had a strong visual sense and has embellished his copy of Good-bye with evident relish. Every available space on the sixteen leaves of endpapers and prelims is crammed with cuttings, and at all angles. Any subsequent blank pages, or parts of pages, such as ends of chapters, are similarly utilised. There are numerous reviews of Good-bye, both good and bad, the latter including Blunden’s damning indictment. When a positive review is by someone Sassoon had thought his friend, like the poet Robert Nicholls, he has pasted beneath it a cutout headline, printed in red, ‘Special Mate Article’. In the case of a glowing, but unsigned review in the TLS, having failed to find a suitably dismissive caption, he merely adds his own comment: ‘This review caused Max Beerbohm to give up taking the Times Literary Supplement’. He includes, presumably with tongue in cheek, a newspaper ‘puff’ for Good-bye, together with snippets from the gossip columns on the high value of the copies with the subsequently suppressed passages. Articles and letters to newspapers about the book’s inaccuracies are cut out and inserted at the relevant point, such as an angry rebuttal by ‘Black Watch’ of Graves’s charge that the Scots were cowards at the Somme and ran away. The most notable letter, however, is not cut from a newspaper but the original itself, a response from Cape, to Sassoon’s visit of 13 November 1929 with his threat of an injunction: ‘After your call this afternoon I made arrangements for the cancel pages to be printed and to have them pasted into such copies [. . .] as have not already left our premises’. Sassoon cannot resist showcasing his triumph and this letter is pasted prominently on the verso of the title page. Since Blunden and Sassoon had finished annotating Blunden’s copy on 7 November, almost a week before Sassoon’s visit to Cape, it seems that is was the annotating of this second copy which provoked Sassoon to make his demands of Cape and finally bring his friendship with Graves to an end.

Sassoon’s copy of Good-bye makes it clear how much his opinion of Graves had changed after the advent of Laura. The most entertaining of the insertions are the selection of commercial illustrations, photographs and drawings which poke fun at the two of them. A perfectly innocuous frontispiece photograph of Graves is rendered absurd by the cutout caption ‘LITTLE JACK RABBIT’ pasted beneath it. And Eric Kennington’s fine pastel drawing of Graves is accompanied by an even more ridiculous caption from a newspaper: ‘Breeding will tell | Just why this should be is difficult to say; for, as previously stated, there were no exceptional gadgets on the model’. Sassoon conveys his opinion that Graves can be something of a ‘stuffed shirt’, at the end of a chapter on Oxford, simply by including a cutout advertisement for a white shirt-front. If he thinks Graves is talking nonsense, he merely inserts an incomprehensible extract in Chinese, Swedish or Dutch. His allusions to Laura are aimed at achieving a similarly absurd effect; there is an advertisement for ‘The Central Cycle Riding School’ and a picture of two ladies on bicycles in Edwardian costume, captioned: ‘Spinning down the road from Calais to St Omer’. But the references to Laura also reveal the depth of his dislike of her; one illustration, for instance, shows a man and a woman struggling together, with the caption, ‘You shall not die! You shall not die!’, an unmistakable and highly unsympathetic allusion to her attempted suicide earlier in the year. Best of all perhaps is Sassoon’s replacement of Graves’s subtitle, ‘An Autobiography’, with the cutout title of a popular children’s book by xxxxx, illustrated by xxxxx, ‘MUMMY’S BEDTIME STORY BOOK’. It is all sheer make-believe, he is implying. (See title page opening.)

Though Graves never saw Sassoon’s and Blunden’s annotations, Sassoon had made his objections clear to him. But he refused to apologize for any inaccuracies in his book, arguing that there are two kinds of reality. One is what actually happened, which belongs to the historian, or chronicler of Regimental Histories: the other is what it was like, what happened to the person who was there, which belongs to the individual. While Sassoon and Blunden strove conscientiously for strict factual accuracy – and may even have lessened the immediacy of their accounts by doing so – Graves had no time to try for it. Nor would he have done so had he been able, he claimed. For, as he explained in his ‘PS to Good-bye to All That’ (published in But It Still Goes On [1930]), factual accuracy did not seem to him the prime aim in the personal memoir:

It was practically impossible (as well as forbidden) to keep a diary in any active trench sector, or to send letters home which would be of any great post-War documentary value; and the more efficient the soldier the less time, of course, he took from his job to write about it. Great latitude should therefore be allowed to a soldier who has since got his facts or dates mixed. I would even paradoxically say that the memoirs of a man who went through some of the worst experiences of trench warfare are not truthful if they do not contain a high proportion of falsities. High-explosive barrages will make a temporary liar or visionary of anyone; the old trench-mind is at work in all over-estimation of casualties, ‘unnecessary’ dwelling on horrors, mixing of dates and confusion between trench rumours and scenes actually witnessed. (pp. 41-42)

Paul Fussell goes so far as to argue that ‘if Good-bye to All That were a documentary transcription of the actual it would be worth very little, and would surely not be, as it is, infinitely re-readable’.

Good-bye to All That sums up the fears and hopes of the generation who experienced the war with a pertinence that could hardly admit of a strictly literary treatment. The point of Blunden’s and Sassoon's non-journalistic memoirs was that they had not rejected the past, even though they had lost it. Their accounts are poignant because they are set against, because they contrast with the decencies and the beauties and the quietness of the traditional past. Now Graves [. . .] was a rebel, and he was in revolt. This revolt was not against the kind of tradition which Blunden and Sassoon loved, and for which their nostalgia is so compelling: it was against the present. Sassoon and Blunden, reclusive men, were too removed from the real present to be able to bear it. What moved them was the loss of the ‘old things’; war above all, symbolized this.

Fussell argues, convincingly, that we need all three viewpoints, Graves’s as much as his more conscientious rivals, that together, not separately, they have ‘effectively memorialized the Great War as a[n] historical experience’. (ix). They are all three ‘the classic memoirists’ of the period, the more self-consciously literary works of Sassoon and Blunden balancing Graves’s more spontaneous account. Though Good-bye, unlike Fox-Hunting Man, did not win any literary prizes, it sold very well indeed. Within a month sales had reached 30,000, easily exceeding Sassoon’s impressive sales of 15,000 in just under three months. Since Graves’s most compelling reason for writing his memoirs was, he candidly admitted in its opening paragraph, ‘money’, his aim had been achieved.

As for Sassoon, a poem written shortly after the publication of Good-bye but never published in his life-time, suggests that the chance to vent his spleen in his own copy had had a cathartic effect:

Should one assume a mild magnanimous look

When effigied and blurtingly displayed

In a – presumably – profit-seeking book

By someone scribbling on the downward grade?

Resentment asks permission to protest.

Jean Moorcroft Wilson is the author of numerous books and articles on World War One poets and poetry, including a two-volume study of Siegfried Sassoon – Siegfried Sassoon: The Making of a War Poet, A Biography (1886-1918) (1999), and Siegfried Sassoon: The Journey from the Trenches 1918-1967 (2004).

We gratefully acknowledge the Times Literary Supplement for its permission to republish this essay from its 2 February 2017 edition.