|

Search Help |

|

Links Robert Graves Website Other RG Resources |

Feature

David Graves's Last Days: A Fellow Fusilier Remembers

Captain John C. Bennett served in the Royal Welch Fusiliers together with my brother David Graves, and was with him when he died in action in Burma in March 1943, three months before I was born. He spoke to me about him on 3 March 2007, and again on 18 April 2010 (the text in italics is from the second conversation). John Bennett died in November 2011, aged 95.

L.G.: I’d like to ask you about David’s last days, and the battle.

But I’d better start at the beginning: when did you first meet David?

J.B.: I first met David about the end of 1941, when what was left of the regiment reformed and moved into the Cheltenham racecourse. We were getting reinforcements, having lost a lot in France: new officers, new men, and there were lots of people to retrain. We didn’t know at that time, of course, that we were going into the jungle, as most of the country was preparing for the Germans to get to us. There was a great deal of training going on, and it entailed long marches in very cold weather up into the mountains, all over the place, to get people as fit as they possibly could be. In addition, there was unarmed combat, bayonet fighting training, shooting skills and map reading lessons.

At one particular stage, because the Germans had got into the Low Countries and Norway and Sweden, we thought we would be going there to fight against them, and at that time every man and every officer, every person in the regiment was fitted with white clothing, skis – or things that looked like skis. So everyone conjectured, having seen that these were being kept in the stores, that very shortly now, once the Germans had settled down, we’d be after them there. But then, some fortnight afterwards, along came another batch of clothing which was for service in the Far East or the Middle East. I think they were trying to put off any spies that there might have been in the area. Anyway, it didn’t only fox the spies, it foxed us as well, because we didn’t know where we were off to.

L.G.: So when was this, 1941?

J.B.: Yes, ’41, beginning of ’42. And then, well, we really became a regiment again because the youngsters that we had taken in, they were being drilled, they were being marched, and they were being physically educated, as it were. When they came in they were recruits and by this time, after a year, they were really ready to soldier somewhere. There was a nucleus, of course, of welltrained and seasoned soldiers who had been in Dunkirk; we had those and they proved to be very good because they were… sort of the skeleton of the army and experienced men who had been through it.

And of course we came to the point where it was our turn to go abroad. And I think, having discovered this later, we were due to go into the Middle East and open a channel up through into Russia so that we were covering a route which supplied tanks and other arms into Russia. The convoy that I was in – it was a massive convoy, it came from Liverpool, Newport, Glasgow and other ports – joined up in the Atlantic and half of it hived off into the Mediterranean. But every day on board ship, on every ship that was there, there was something going on, or something to do with soldiering, signalling, marching, PE, wireless work, map reading… And then we discovered – just before we got to Cape Town – that we were going to take Madagascar from the Vichy French because they were harbouring German and Italian ships there. We had two days in Cape Town where there was a lot of hard work. We marched all the way round the Cape, about twenty odd miles, and had one night and one day there. We were billeted in a police cadet school, fed well and had access to boxes of South African fruit. There were three well-stocked bars in the camp, one for other ranks, the other two for NCOs and officers. All ranks were able to enjoy a very pleasant evening.

L.G.: And was David with you then, at that time?

J.B.: Yes, yes, he was with us. And then we started to march back again the following morning, back to the docks, which were about twenty miles away, and a motorcycle pulled up next to me: the CO wanted me up front. So I go up front, on the back of the bike, and the CO says to me, ‘I want passes for twenty-four hours for every man on board ship’, and this released me from a march back! But I had the passes all ready for them, and I was all shaved and tidy by the time they arrived. We issued the passes and then the men could go away for twenty-four hours. And I will say this about the South African people: they were marvellous. The next day there were hundreds of cars pulled down onto the dockside. A family would come along and say: ‘Right, I’ll take three with me and you take two’, and so on, and eventually everyone had somewhere to go for the day. And they were very nice – the lady that I went with (my two friends and I), her husband had been captured in the desert and was a prisoner of war in Germany. But we still had a very nice time with the family.

After our twenty-four hours there we set sail about five o’clock in the evening before the sun went down and just after the sun went down, when the convoy was way out at sea, there was a heck of an explosion and the next thing I heard was that the ship which carried all my carriers and the ambulances and all the rest of it, had either hit a mine or had been blown up some way or other, off Cape Town. And then half the convoy, instead of going to take Madagascar, went east through the Indian Ocean to Bombay. That was the beginning of our journey which eventually ended up in the Arakan, northern Burma.

Then, of course, training started again. We had never been in the jungle before, our previous training had been for open warfare in the West.

Even though initial training was done in light equipment, the heat was hardly bearable, and wearing a steel helmet didn’t help…

L.G.: Sticky heat?

J.B.: Yes, very sticky heat. Gradually the amount of equipment and ammunition we carried was increased until we carried full fighting order.

Ten minutes after starting work the backs of shirt and armpits

were black with perspiration. But as our blood thinned and we got used to the heat we trained in rocky terrain, dry scrubby country, jungle and mountain areas. Everyone worked very hard. Then came the great day when we learned that we were going into Burma.

I was given the task of taking the brigade Bren gun carriers (about thirty), plus ambulances, shells and ammunition from Bombay by rail to Calcutta, plus the crews. It took about six weeks and it was the experience of a lifetime. I forget the number of times I had to change from narrow gauge rail to wide gauge and vice versa. Also crossing the tributaries of the Ganges River by pontoons; loading and unloading ammunition and shells…

We then left Calcutta by road for Chittagong, a port in Northern Burma, where we eventually joined up with the rest of the regiment. They were already well established there, resting in pine woods.

The first day there we were attacked with five Japanese aircraft who strafed down through the wood and struck the wrong half of the road, so there was no one hurt at all. But it woke people up to the fact that we were now in a dangerous country, or a dangerous part of the country. Then it took, I should think, another three months to get to where the fighting went on, actually hand to hand stuff. We spent time in Bawli Bazaar, and all the other little, well, quite sort of small little towns and villages all the way down the coast of Burma, occasionally being shot at by aircraft. We had two American newspaper people attached to us for a while who were coming down to report on what we were doing, and they went off in a boat one morning down the river towards Maungdaw – where they were going to stay for a while before we got there. And they were back within twenty-four hours: they’d been struck by the Japanese aircraft and both of them had been wounded. And that was that, a little bit of an adventure!

There were occasions like that when we stopped at the villages and obviously there was a spy system working between the people who lived there and the Japanese, because whenever it was possible we stayed in undergrowth in woods and places like that and then I’ve counted times when Japanese aircraft, fifty at a time, would come over –

L.G.: Exactly where you were?

J.B.: Exactly where we were…

L.G.: So they’d been informed.

J.B.: Yes, they’d been informed. And the leading aircraft would fire at us and then every aircraft would drop a bomb. It was blanketing and they set fire to all the installations and goodness knows what and that… But one of the benefits we got from it was that on their return journey – they must have come a long way – they carried special-supply petrol tanks on the aircraft, and they dropped the supply tanks as they became empty. And the tanks made wonderful baths – when you cut the top off!

And then the eventful day, the big day in the regiment’s life was when we came to Donbaik. Donbaik was a village that we didn’t see because it was about a mile from where the main trouble was, where the Japanese had built bunkers – I’ve got to congratulate them on the fact that they were very, very good tactical soldiers, the Japanese. For example, when we stopped we usually dug trenches and put a bit of barbed wire round and then we sat there waiting for them. The Japanese didn’t do that. They put bunkers in particular places where, for example, the river ran around or near it, so that anyone attacking it had to go through the river first, or through some sort of hazard, before the attack could be made. And we discovered one position at Donbaik where we thought there were two or three bunkers – but there were more like six bunkers, all supporting one another with machine-gun fire. And in front of which other regiments had attacked, native regiments and other regiments that I didn’t know about, but their skeletons lay in front of the positions, having been mown down before they’d had a chance to attack the bunker. Then came the 16th, 17th and 18th of March, when we made feint attacks by pretending to cheer as we went in. Nothing happened. We did this on the 16th, 17th. Nothing happened, not a shot was fired from the enemy and on the 18th when we actually went in and cheered as we went, all hell was let loose and that was where my friend and many of my friends were killed. Mainly sitting on top of the bunker, unable to get into it, being mortared and shelled at the same time by the Japanese. It was a very sorry day for the regiment. L.G.: John, what did the bunkers look like?

J.B.: The bunker we attacked was about seventy-five yards long and thirty yards wide. It was covered with a roof made of bits of logs, branches, bits of brick, wood and mud. We were given orders to take the bunker, which was quite impossible. On either end of the bunker there were ports, holes big enough for them to shoot out from but not big enough for us to throw a grenade in. When the attack took place, they shot at us from the two holes and our men had to dodge the bullets that crossed in front of them as they ran forward. The Japanese also hid in trees behind the bunker and shot us from there, or dropped grenades when the attack took place. It was practically impossible to get through.

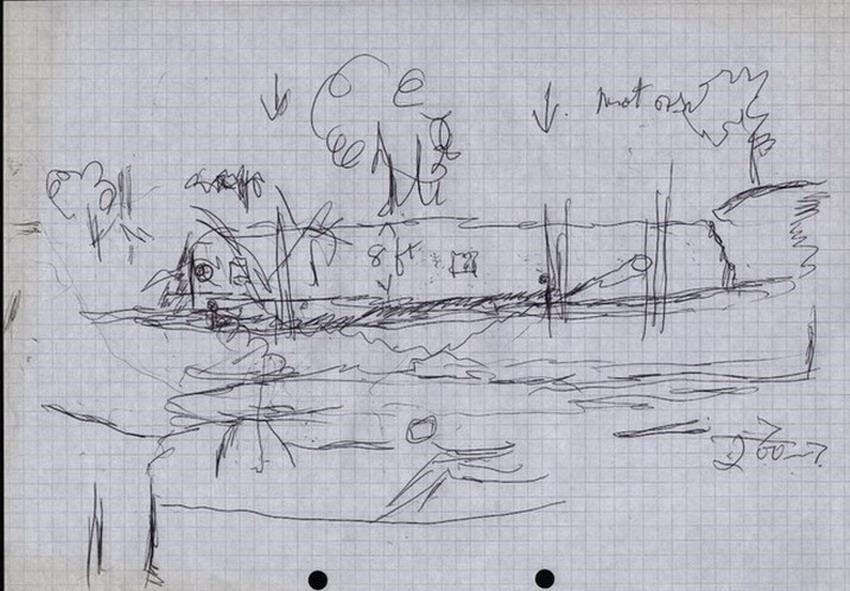

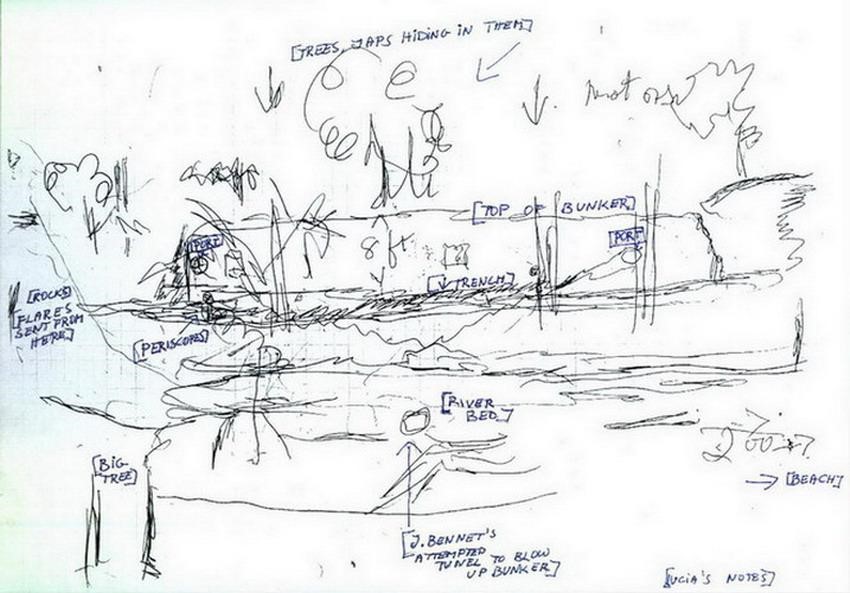

John Bennett’s drawing with Lucia Graves’s notes

The bunker stood on the other side of a small river. The beach was on the right, about 200 yards from where we were, and when the tide came in the river swelled so you’d have to wade through it, about two feet high, to get across. When the tide was out, then you could cross more easily: the ground, though muddy, became quite firm. All around the bunker there was a trench, and the top of the bunker was about eight feet from the ground, so it wasn’t easy to get out of the trench onto the bunker, especially with all that fire coming at you. There were a few places where you could get a footing and heave yourself up. From inside the bunker the Japanese used periscopes to see what was going on. I shot at a few! They also hid behind shovels they had used to build the bunker. These had small holes in the metal and were covered in mud for camouflaging, and the Japanese hid their faces behind them. All in all, it was impossible to get at them, and the attack should never have been ordered.

When the whistle blew for the attack to take place, there were three regiments there, so about three hundred men went in the first time. The tallest men, with the longest legs, were chosen for the first attack – in the Welsh regiments there were a lot of shorter men, who were kept back for the second attack, myself included. David was tall so he went with the first attack. Of course, there never was a second attack, it was cancelled because it became obvious that we wouldn’t achieve anything and just lose men unnecessarily.

L.G.: You say that you saw David fall into the trench and then get out of it –

J.B.: I saw him get out of the trench and then he went up the side of the bunker and then – disappeared from there. He was one of the first to get there. And it was not only he; there must have been about fifty people who did exactly the same. When the attack went in, it went in as an ordinary attack with bayonets fixed and within four minutes there was mayhem; people bewildered, shot, wounded, disorientated, and disillusioned. And as I’ve written, my feelings are – and a lot of other people’s as well – that the attack should never have been done, or should never have been ordered to be taken by the bayonet.

I’m pretty sure David must have died within the first few minutes because he was strong and full of beans and would have got away if he’d been able to. It was tragic, so many died. It still keeps me awake at night to remember it.

After the attack, when the second one was cancelled, we were told there was nothing we could do until the morning. But I was ordered to send off flares with parachutes over the bunker, at irregular times, so the Japs wouldn’t be able to work out when the next one would come. There were some rocks on the left hand side, about 150 yards from where the bunker was. I had to cross the little river first, on some planks, then I stood on a rocky ledge and fired the flares from there. I had to keep watching which way the wind was blowing, to make sure it lit up over the bunker. All night these flares flew high above bunker – it looked as lit up as a street in London. I could see the bunker, and the men, dead or wounded, lying there. Some were moving – well, writhing mostly, but you couldn’t make them out individually, it was too far away.

During the next few days I tried to build a tunnel from the river bed to the bunker. I thought if I could get far in enough we could blow the bunker up. But I couldn’t make it long enough.

From then onwards we watched the bodies blow up in the heat of the sun – flies, which were a pest, the inability to eat anything:

we’d open a tin of bully beef and there were flies on it and you knew where the flies came from . . .

L.G.: And of course you couldn’t go and collect the bodies?

J.B.: No, the bodies were out in front of us, about thirty yards away and the Japanese were still in their bunkers. We stayed there – I stayed there with my men for at least ten days, within grenade distance of the Japanese positions. We did patrols; we did patrols along paths where the telephone wires were, so that we knew they weren’t being cut during the night. They were very, very tired men who did patrols every two or three hours, and we got to the stage where, as the moon moved around in the sky and it was dark in the undergrowth and among the trees, you could swear that the trees were on the move or there were bodies that were moving around there. As the moon was moving, with the clouds and the rest . . .

L.G.: Of course. And you said, you were explaining earlier, that when all this happened and all those men were killed, including David, who had got out of the trench and onto the top of the bunker, after that, some of the wounded men were able to get off.

J.B.: Yes, the Commanding Officer, Colonel Williams, spoke both English and Welsh – obviously, it was a Welsh regiment. And he commandeered some loud-hailers and microphones from the gunners’ regiment and he spoke in Welsh and guided some of the men off the top of the bunker. He led them round the back of the bunker and into safety. That was in the first few hours after the attack. Men did come off, some of whom were wounded, and a lot who weren’t, they just got out there and didn’t know where to go from there. They came down and I can’t remember how many there were of them, but it was quite substantial I’d say. But there were still some who were very badly wounded up there and some who would never move again because they’d been killed or died up there. Then the CO considered putting B Company in, they were a reserve company at the time, to try and get to the top of the bunker and help rescue the men who were isolated there. But as the men moved forward the Japanese opened up with their machine guns and because of the risk of losing more men Colonel Williams called off the attack.

L.G.: And did you then throw some grenades?

J.B.: Yes.

L.G.: Could you explain?

J.B.: There was a narrow trench in front and around the bunker. In it were Japanese observers who at intervals raised wellcamouflaged periscopes which spied on our movements. When seen they were quickly dealt with, usually with grenades.

On arrival in the Arakan, Lord Louis Mountbatten described the Japanese as ‘the little yellow bastards’ and told us that we were going to hit the hell of out them. The Japs we shot were men of the Japanese Imperial Guard, all nearly six feet tall and very brave. Not only were they in the bunkers but also in slit trenches and foxholes around the bunkers. Quite often, first thing in the morning, one would stand up, stretch his arms and muscles and before it was possible to aim a gun on him, he would disappear again.

L.G.: So then, whoever it was, decided to blow up . . . to destroy the bodies?

J.B.: Yes, after four or five days. Well, because of the stench of the dead bodies and the flies which were dreadful . . . Where the order came from I don’t know, but I think that my CO must have been partly responsible for it, because it was unbearable there, it was impossible to eat anything and the smell of the decomposed bodies was dreadful. Wherever you went the stench was there. Then we moved back about twenty yards, thirty yards, and the gunners put down a barrage which blew all the bodies away. It improved the situation just a little bit . . .

L.G.: That would explain why David was never identified and could never be – you know, actually described as ‘killed in action’.

J.B.: Yes, that’s right. All the bodies, all the bodies that were on the tops of the bunkers were destroyed, and bits blown away because of the stench and the flies . . . I think that is why he was described as ‘Missing on 18–3–43’.

L.G.: And you nearly went in too. You were stopped from going in –

J.B.: I was stopped from going in –

L.G.: Or you might have had the same fate as David.

J.B.: I would have had the same thing exactly. And the men weren’t unwilling to go, they were all ready to go, particularly to get some of the live people off the top of the bunker because they were all friends and all sort of part of the family there –

L.G.: Through all the bullets –

J.B.: Yes, yes, and I mean, there was so much going on, there was shooting, and shells bursting and people milling about not being able to do anything, wounded and . . . it was a very dreadful situation. Anyway, Colonel Williams pulled us back and he said: ‘Don’t do any more, get back, and back into safety.’ Then he got the loud-hailers and spoke to the people, and then some came off. I can’t remember when the firing stopped when he was speaking to them, but some came off and a lot of them were badly wounded.

Then, when the bodies had been cleared, we just sat there waiting for something to happen. And we then started having attacks on us, not from the people who were in the bunkers but freelance Japanese who were coming in bands trying to infiltrate and to cut us off from the main parties who were behind us. And there was fighting going on, as well as just sitting there waiting for something to happen. The RAF came along and dropped bombs, sometimes in the wrong place – they bombed the village of Donbaik when it should have been the bunkers at Donbaik and not the village. We did all sorts of things to try to beat the Japanese there: I got men working on that. There were a lot of ex-miners in my regiment and they’d worked in the pits and knew how to dig, and we were digging tunnels towards and under the Japanese lines, but before anything could happen, then the fighting outside started again so we had to pack that in and just defend the area. Then, after about ten days, I was withdrawn from the front line with my chaps and we moved back about 200 yards. The story is in the book when, having settled the men in – we’d been there for about an hour and it was the first real rest they’d had a chance to have – firing started from a Japanese gun. He laid down a smoke shell first, which indicated that there was heavy explosion coming after that, when he’d found his range. And then the heavy stuff came. And just before it started, I was lying in a hole which somebody had slept in before I got there, and I looked up and there were bullet holes in the tree above me and I thought, well, there’s a machine gun somewhere out front and the bullets are going into that tree. So I said to my batman, ‘Roberts, could you get me out of here and find me a decent hole, away from this bullet hole?’ So he moved me and I had a hole, a foxhole behind a rock. I got in there and the firing increased. Just then a man came around, the quartermaster sergeant came along with another man carrying dixies of food, soup or something: ‘Come on, come and get it, come and get it’, and then the shelling started again. He jumped into my hole, which I’d just vacated, a shell hit the tree and smashed his head, killed him. The shelling went on for about half an hour and then we expected that there might be an attack after that but nothing . . . it went quiet again.

We were there for another week, sniping again, being sniped at, being attacked, patrols coming in during the night. And then, because of the casualties and the danger which the dressing station was in, because of all these people who had to be dressed with wounds and all the rest of it, with just the doctors and a few orderlies doing it, and the Japanese coming around the back of us, the CO decided we’d move back two or three miles. We did that, and then it was a question of trying to find out where they were and getting rid of them. It was winkling, if you can imagine getting winkles out with a pin – but this was getting rid of Japanese from foxholes and slit trenches with the bayonet, from where they were causing a lot of casualties.

The Arakan is part of the Mayu Peninsula, the sea washed the western side. A mountainous jungle-covered spine about 3,000

Hertfordshire: Rock Road Books, 2005).

feet high ran down the centre and fell to the Irrawaddy River Valley to the east. The Japanese played king of the castle. They had occupied the spine and looked down on us. They had one artillery piece which they used to fire on us and a spotter aircraft which flew low and fed information to the gun. It sounded like a sewing machine and could easily be shot down. For some reason we had orders not to fire on it.

I often wondered why we did not take the high ground, but realised that to supply an army through the jungle with no roads and to 3,000 feet would have been a mammoth task, and on the plain we did have an escape route by sea.

There were pimple-like outcrops covered with vegetation on the plain, which was mainly paddy fields. At night we occupied hillocks which offered cover and were cool after the heat of the day. At night the Japanese came down from the mountain and called: ‘Come on Johnny, we are your friends, we’re Royal Scots, come on Johnny!’ or ‘Come on Tommy, your wives are sleeping with the Yanks, come and join us Tommy . . .’ This would be followed by a stream of coloured tracer bullets. By dawn they would disappear into the jungle again.

Small fighting patrols were being sent out to search for enemy positions and to keep in touch with outposts, and a number of them had been ambushed, and every man and mule in the party had been slashed or bayoneted. As a result it was decided to reduce the perimeter of the area which the brigade was holding and to move brigade HQ to a safer spot. I was asked to provide a party of men to fill sandbags and to assist with the structure. Within a day it was completed and the staff and equipment, radio and wireless telephones moved in. I also provided a Bren gun carrier with driver, ‘Lazy’ Lawrence, for the use of the brigadier.

At this point plans were being made for a major attack which would clear the Japs from the Indin area.

On the evening that the strongpoint was occupied by the brigade intelligence staff, about an hour before dusk, we came under heavy machine gun attack from the north. The only cover were the banks of the paddy fields which we lay in. Then, sometime after darkness fell, ‘Lazy’ Lawrence, the driver who had been left with the Bren carrier for the use of the brigadier, came running into our lines, closely followed by Captain W. Rees, the Intelligence Officer, to tell us that during the machine gun fire the Japanese had attacked the strongpoint and captured all the staff, at the same time smashing all the radio and other communications equipment. Captain Rees had been wounded in the arm and managed to escape; Lawrence had been asleep in his carrier and had got away in the commotion. It meant that all communication was lost with the gunners and the rear echelon headquarters where Colonel B.

H. Hopkins was co-ordinating details of the final attack with other units.

In the meantime, a machine gun nearby started shooting. I ran across to it and shouted, ‘Stop firing!’ It continued to fire and I ran close to the gun and shouted again, ‘Stop firing!’ After a few more rounds the gun stopped and I said to the gunner, ‘Did you not hear me the first time?’ There was no answer from him, and when I looked closely he had been shot in the head, with his finger clenched on the trigger.

I think Captain Rees and Lawrence were the only two people to escape from the strongpoint, the others were captured.

L.G.: What was their fate, what happened to them?

J.B.: They were killed. The brigadier was a very brave man and the last order he gave was to our gunners to shell the area where he and his captors were. He was killed by his own men, by his own guns, and a lot of Japanese too.

L.G.: But the communications had gone –

J.B.: Yes. The attack had to be postponed. However, I took two of my men in a carrier through the Jap lines to the beach, then north to where Colonel Hopkins and the rear echelon were, a distance of about three miles. The Jap gun from the hills chased us up the beach, but we were given something to eat, new wavelengths for the radio and more information about the attack. As a result, communications were resumed and the attack went ahead. It was a great success, on our colours it is shown as the ‘Battle of Indin’. Not many Japanese returned to Japan from it . . .

L.G.: It was a turning point?

J.B.: It was a turning point, we ripped them to shreds . . .

L.G.: Well, after all you’d suffered you must have felt it was about time.

J.B.: They came out into the open and had nowhere to go; they were shot down. That was the last thing that we did there. We then got out of it.

L.G.: And then you went to India?

J.B.: Yes, and then we went back to India.

L.G.: I just wanted to ask you one more thing . . . . When you were with David in those last days, what was he like with his soldiers and his friends?

J.B.: I would describe him in the nicest way, just like my daughter, phlegmatic, calm, unexcitable, with a quiet sense of humour. And no histrionics, just a nice fellow, a nice, very quiet, unassuming fellow . . . a good soldier. His men liked him, he often took his turn at carrying the Bren guns to relieve his men. He was a good leader.

Lucia Graves and John Bennett, 18 April 2010

A few days before we moved into the positions at Donbaik, five of us sat in a circle around a small red fire with a half petrol tin of rum. David was in the group; Lieutenant Jack Smith, an exLondon policeman; Lieutenant Watkins and myself and one other whom I cannot now remember. We sat until the early hours of the morning listening to Jack Smith tell rather dirty stories. I can still remember one of them now, but I’m afraid I couldn’t tell you . . .

L.G.: No, better not! But you had fun!

J.B.: It is rather a rude and vulgar . . .

L.G.: Yes but you had fun, it was a moment of relaxation.

J.B.: Once a year I tell that story . . . . And that evening we sat – none of us smoked – we sat around this little bit of a fire, which was just a red glowing bit . . . As a matter of fact, at one time when we were there, a shell dropped about ten yards in front of us and the wind blew the cordite, we could smell the cordite, but nothing happened, and then a few days after that . . .

I tell you what. When we were living under normal conditions in Ahmednagar military camp, the training conditions for both officers and men were very hard. Some of the schemes took two or three days under wartime conditions, necessitating loss of sleep, long route marches, attacks using live ammunition, and shelling.

Everyone at the end of the scheme needed a bath, food and sleep. David was a big lad, well built and about 5 feet 10 inches tall. When he had seen to the needs of his men, he would bath and change his clothing, turn up in the mess early for his meal and whilst waiting, devour half the contents of the fruit bowl near him, before eating an enormous dinner! He was a big chap and needed it.

There was one occasion when I felt a little sorry for him. A few of us were talking in the mess about home and general things like school and holidays, when David said that he did not like school holidays as when at home he slept in a caravan in the orchard and rarely saw his dad.

David loved soldiering, he was a good leader and popular with his men, well liked by his brother officers. He was a very brave and fearless young man. He and the officers and men who died at Donbaik were killed unnecessarily on the orders of someone who gave the order that the bunker be taken by the bayonet.

Lucia Graves is a writer and translator. She lives in London and in Deyá, Mallorca.