|

Search Help |

|

Links Robert Graves Website Other RG Resources |

Critical Studies

Poetic Nonsense: Robert Graves, The White Goddess and Children's Poetry

Nonsense and nursery rhymes are among the most undervalued aspects of the oeuvre of Robert Graves, and yet, if examined with the seriousness that informed their creation, they reveal a range of meanings and beliefs that can complicate and inform our understanding of Graves’s poetics. With notable exceptions, scholars have preferred to hive off Graves’s nonsense and nursery rhymes, and to regard them as something akin to self-indulgence (in the order of a weakness for puns). But there is abundant evidence in Graves’s letters, criticism and in the poems themselves, that his notions of nonsense and nursery rhyme embraced complexity, depth and originality, and that they sprung from the same deep pools of thought and feeling that nourish all of

Graves’s poetry.

There is also evidence to suggest that in his early twenties, Graves gave serious thought to becoming a children’s author. In a letter to Siegfried Sassoon in July 1918 he writes, ‘if I ever make any name for myself for poetry & stories, it’s the children’s stunt that I’m going to succeed in, I’m sure’.1 Although his certainty waned after the publication of Fairies and Fusiliers,2 and he tells Marsh ‘I have finished with the Fusilier kind of poem: and am not going to specialise in children’s poetry either but write just exactly what comes nearest my fancy’, children’s rhymes continued to captivate him; in 1919, after preparing the manuscript of Country Sentiment, he tells Marsh: ‘hope you like the new one at the end of the Country Sentiment book. And the nursery rhymes some of which, who knows? may survive the longest of any’.3 It is not unreasonable to suppose that over the period of three years or more, Graves believed he had a particular gift and temperament for writing children’s poetry and wondered if perhaps he was destined to be a children’s poet.

By the time Country Sentiment appeared, Graves had published five books, four containing poems that could, and eventually would, be issued for children. Some number of these had been intended for a book of poems that he had been planning for three years, whose working title, The Penny Fiddle, would become the title of his 1960 publication.4

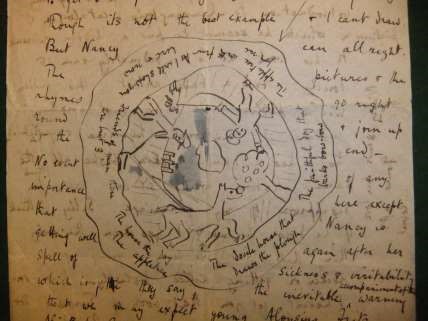

He had begun collaborating on the book in 1916 with Nancy Nicholson soon after they met. The 1918 letter to Sassoon quoted above contains early drafts of two of those poems, along with another children’s poem that would remain unpublished during Graves’s lifetime. It also contains a fifth children’s poem integrated into the drawing of a plate, a crude copy of Nancy’s design, which Graves tells Sassoon belongs to a set of plate designs they have already sold to ‘Goode’s, the big china firm’ (figure 1).5

Fig. 1

Drawing and poem in a letter from Graves to Sassoon, July 1918

(The Henry W. and Albert A. Berg Collection of English and American Literature, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations)

About the same time he met Nancy, scarcely three months after being badly wounded at the Battle of the Somme, Graves had praised the children’s poetry of fellow Georgian Walter de la Mare in a letter to Marsh: ‘When next I come to London I do so want to meet de la Mare. I have been reading Peacock Pie again and it improves every time’.6 De la Mare, a poet, father, and spinner of ghost stories in old-fashioned rustic diction, must have seemed the personification of domestic felicity, or as near to it as a writer could get, and perhaps as Graves envisioned life after the war, writing children’s poems took on the aspect of a poet’s privilege. Meeting Nancy undoubtedly spurred Graves to think about children’s poems, and thinking about children’s poems undoubtedly encouraged him to think about Nancy.

In the 1929 edition of Good-bye to All That, Graves states that the source of their initial attraction was ‘child-sentiment’: ‘my child-sentiment and hers [. . .] answered each other’.7

Collaborating on an illustrated book of children’s poems became the reason for continuing their relationship, for, as Richard Perceval Graves notes, Graves had otherwise taken little notice of Nancy.8 Graves writes simply, ‘I began a correspondence with Nancy about some children’s rhymes of mine which she was going to illustrate’ (p. 320).9

Graves also records that during the war he had developed other strong poetic connections to children and poetry:

[Siegfried and I] defined the war in our poems by making contrasted definitions of peace. For Siegfried it was hunting and nature and music and pastoral scenes; with me it was chiefly children. When I was in France I used to spend much of my spare time playing with the French children of the villages in which I was billeted. I put them into my poems[. . . ]. (p. 277)

These poems he published in Fairies and Fusiliers.

Frank L. Kersnowski suggests that reflections on children were ‘brought into’ other poems, such as ‘Give Us Rain’, which Graves published in Country Sentiment (along with some of the poems that he had intended for The Penny Fiddle).10 The concluding lines of ‘Give us Rain’ focus on children as the victims of war: ‘But the Flags fly and the Drums beat, denying rest, / And the children starve, they shiver in rags’.11 Kersnowski admits the images do not move us, however inclined we are to feel pity for the poem’s subjects, and he commends Graves for showing ‘good sense and taste in not reprinting it’ (p. 89).

A more ingenious poem in the same collection might also have sprung from observing children in France. ‘Country at War’ reflects on what the English children are doing back home safe from the horror of battle:

Children play at shop, Warm days, on the flat boulder-top,

With wildflower coinage, and the wares Are bits of glass and unripe pears.

Kersnowski describes the setting as definitively English (p. 90), and yet could it not have been coined upon the play of French children? The analogy between children playing at shopkeepers and entreating God to witness their innocence when their play gets out of hand – which may remind us that Graves understood the war as a conflict between trade rivals (Good-bye to All That, p. 288) – and frenzied soldiers who murder seemingly against their will is nicely complicated if we want to see the French children behind the pretty English façade. The psychological tension between the biological need to protect children in harm’s way and the hostility aimed at individuals whose unfledged irresponsibility brought endless misery is more acute when they are, figuratively, the same persons, and the soldiers who have been enlisted to protect them are also the instrument of their ruin and death.

Announcing that a book improved with each reading, as Graves had done with Peacock Pie, may be a way of delicately insinuating that it was not so hot to begin with. But even if Graves had not been thinking that life in a village penning nursery rhymes was not worth living, he may have come to think it later. His explanation in Good-bye to All That for avoiding psychiatry and thus banishing his ‘Pier-Glass haunting’ and suffering the fate of becoming ‘a dull easy writer’ (p. 369), suggests as much, even though ‘The Hills of May’, and ‘The Magical Picture’, poems of this period, neither dull nor easy, do find their way into The Penny Fiddle (1960).

The fear of writing predictably, a reflection perhaps of an emerging poetic tendency toward what Graves called ‘emotional thought’, forms the subject of a 1923 poem, ‘Interlude: On Preserving a Poetical Formula’, which touches on Graves’s attitude toward his nursery rhymes in an ostensibly dismissive way.12 First published in Whipperginny, ‘Interlude’ consists of two parts; in the first, Graves appears to be telling readers that whether his work tackles difficult and even horrible topics, or returns ‘childishly’ to ‘Mother-skirts of love and peace / To play with toys until those horrors leave me’, he is writing authentically, he is himself: ‘The SPIRIT’S the same, the Pen-and-Ink’s the same’. If he had abandoned writing for the general public in 1921, as he claimed in Good-bye to All That, then, perhaps the poem represents something of a rearguard action, or perhaps the audience for the poem is Graves, himself, the reader over his shoulder, whom he would call ‘old enemy’ in that poem (Graves, ‘The Reader Over My Shoulder’).

In the second, parable-like part of ‘Interlude’, subtitled ‘Epitaph on an Unfortunate Artist’, he invites the reader to read (him) with a critical eye, and ear:

He found a formula for drawing comic rabbits:

This formula for drawing comic rabbits paid. Till in the end he could not change the tragic habits This formula for drawing comic rabbits made.

Recycling the awkward phrase ‘drawing comic rabbits’ and knocking down obvious end rhymes, this epitaph demonstrates, backwards, the kind of musical sensitivity that ought to be a prophylactic against dull, formulaic writing, and in that regard it becomes a parody of a parody, most sensitive where it seems least, and a gentle poke at the audience it postulates in the poem’s beginning (readers, critics, even, who knows, his older, nimbler, self) for whom royalties seem the sole criterion by which to judge a book of poems. In view of the rough treatment of ‘toys’ in

‘Interlude’, one gets the impression that the principal cause of Graves’s concern about writing formulaic poems is his nursery rhymes (psychologically necessary to distract oneself from the terror of history though they may be). And yet, the compactness and deceptive simplicity of the poem – modelling a kind of agility and ironic depth while feigning clumsiness, being in fact the very opposite of what one seems to be – are the hallmarks of his finest nonsense. Is Graves cleverly apologising for being too clever, or cleverly not apologising? One might suggest that the apologetic or concessionary tone implied by the title is a ruse, and that Graves was attempting to demonstrate that what seems formulaic, or perhaps mere child’s play, is more complex and marvellous than readers realise – or, unless they read very carefully, will realise. In any case, he would continue writing children’s poems and nonsense into his seventies.

I would argue that nursery rhymes appealed to Graves as a child and then a young poet for reasons more fundamental than profit or escape or degree of difficulty, that they epitomised, perhaps more than they expressed, a structure of consciousness by which he was spellbound. He implies this possibility very roughly in his earliest published poems: in ‘The Poet in the Nursery’, the initial poem of Over the Brazier (1916), and in ‘Babylon’, published less than a year later in Goliath and David, which begins with the declaration, ‘The child alone a poet is’.

While ‘Babylon’ is philosophically compatible with Rousseauian notions about the transcendental child and society’s corrupting influence, even to the point of echoing Wordsworth’s nostalgic evocation of chapbook heroes from The Prelude, it also expresses a Keatsian discomfort:

Rhyme and music follow in plenty

For the lad of one-and-twenty,

But Spring for him is no more now

Than daisies to a munching cow; Just a cheery pleasant season, Daisy buds to live at ease on.

Despite excluding ‘Babylon’ from his canon, practically from its inception, starting with Poems (1914–26), Graves deemed the underlying question serious enough to acknowledge it three decades later in a ‘stunt’ for which posterity does, in fact, remember him – ‘The White Goddess’:

Green sap of Spring in the young wood a-stir Will celebrate the Mountain Mother,

And every song-bird shout awhile for her […].13

Locating this comment, that children are in fact genuine, if unskilled, poets, in the credo of his most encompassing and ultimately most influential work on poetry, Graves leaves no doubt about its relevance to his deepest intuitions about poetry, and perhaps reveals an underthought to ‘Interlude’ that reinforces the idea of the poem as an integration or dialogue of selves. The alternative discourses of ‘Interlude’ are cognate: wrestling ‘with fiendish darkness blinking threatfully’ and darting ‘childishly [. . .] to Mother-skirts’ are but two modes of invoking the White Goddess.

The relevance of the White Goddess to nonsense and nursery rhyme is explicit and significant. In Robert Graves: His Life and Work, Martin Seymour-Smith conceptualises the Goddess as a ‘factor in the structure of the poetic personality’.14 Although I think the phrase ‘poetic personality’ invites misinterpretation, implying that all poets share the same personality or personality type, or that poetry is determined by psychology – that poets write poetry because they have the personality of poets – I am inclined to admire Seymour-Smith’s approach. However, I would suggest that to avoid this tautology we emend ‘poetic personality’ to a more general ‘structure of consciousness’, and add that this factor is also found in its concomitant within human history. Receptivity to, and the capacity to value, this factor qualify somebody as a poet, with prowess as a writer being a secondary attribute. When Graves writes, in the introduction to Poems 1938–1945, ‘I write poems for poets […]. To write poems for other than poets is wasteful’, he appears to be saying that one writes poems for anyone who can find the truth in poetry, or accept that the ‘aboutness’ of poetry, its intentionality, is truth (in the Greek sense of aretê, or excellence, in the sense of ‘true spiritual feeling of my nonsense’).15 Not that Robert Graves is writing just for a particular writing school. So, changing ‘personality’ to ‘consciousness’ privileges Graves’s own phenomenology and avoids ontological statements such as that the White Goddess does not really exist.

In a sense, the struggle for the soul of Graves’s poetry will turn on the question of whether we ultimately see the White Goddess as merely an imaginatively-shaped reflection of Graves’s own random life experiences, or as a symbol of a quest for being – for aretê – mediated by the elements of experience: whether we ascribe explanatory power to psychology or to ontology.

The Goddess is, according to Graves, always manifested as a phenomenon external to oneself, as a transpersonal agency and the intentional object of poetic vision. Need we continue to write that Graves’s apprehensions are grounded in subjectivity, in personal history, beliefs, psychology, conditioning, receptivity, personality, predisposition and so forth – as though yours and mine were not? Locating the White Goddess within human consciousness rather than a particular personality allows that poetic apprehensions are apprehensions of the human condition and recognises that we have the capacity to criticise Graves in a nontrivial, non-formulaic way that is not restricted to de-legitimising his research or uttering the most hackneyed of phrases, such that in The White Goddess, Robert Graves was creating metaphors for his poetry. Graves’s apprehensions are not relativised to a particular lucky or troubled personality, but available at every moment to all of us: ‘And every song-bird shout awhile for her’ asserts a belief in the universality of poetic inspiration in the most transpersonal sense because it attests to a belief in the presence of the White Goddess even in the intentionality of nursery rhyme and nonsense.

In his ‘green sap’ phase, however, Graves occasionally seems uncomfortable with the childishness of his poetic genius, no more so than when he is professing he is not. In 1922, in On English Poetry, he writes, ‘childish habits in a grown man [. . .] are considered ridiculous’.16 He describes childishness with great theatrical flair, as ‘amazed wondering, sudden terrors, laughter to signify mere joy, frequent tears and similar manifestations of uncontrolled emotion’. Perhaps the equivalence he draws between poetry and childishness suggests a modicum of ambivalence about being a poet, an ambivalence that we see, however couched in artful affirmation, in ‘Interlude’.

In language somewhat similar to Graves’s, Mark Oppenheimer expresses discomfort with poetry in a recent New York Times article about the poetry critic, Stephen Burt:

Being a major poetry critic in the United States today may seem like a dubious honor, almost akin to being the best American cricketer, or a distinguished expert on polka. Yet we still teach poetry to our children, and we still reach for it at important moments – funerals, weddings, presidential inaugurations. We tend to look askance at those who claim to be practitioners, skeptical that their work could be any good.17

Oppenheimer does not intend to mock poetry or poets, and he means to praise Burt through apophasis, by reducing the argument against poetry to an absurdity. But while being an expert on cricket in the United Kingdom, or on polka in central Europe, would not strike us as comical, it would still be of little moment, as games and dancing are appropriate to idle youth (or hauled out like bunting, Christmas ornaments, flags and occasional clothing to dress up public rituals). Neither Oppenheimer nor Graves believes poetry is frivolous, but they both seem to recognise that its marginal social status and peculiar relevance to youth place it at a tangent to mainstream standards of maturity, responsibility, gravity and manliness.

In Graves, such concerns trigger the usual powerful defence in which he attacks those who ridicule childishness as expressing the lordly distaste of the ‘strict classicist’ for ‘the ungoverned Romantic, the dislike being apparently founded on a feeling that to wake this child-spirit in the mind of a grown person is stupid and even disgusting’ (On English Poetry, p. 69). Approaching thirty, Graves publicly acknowledged his own ‘ridiculous childishness’ by summoning up the Romantic valorisation of emotion with its connected valorisation of childhood. In private, Graves showed a comparable sensitivity; in a letter to Marsh, he writes, with reference to his poem ‘Finland’: ‘It was made in a poetry game I played with Sassons once on that set subject. He wrote an extremely decorative sonnet which though most admirably tooled and finished had not the true spiritual feeling of my nonsense’.18

In 1925, he elevates nonsense with ‘true spiritual feeling’ to the stature of ‘poetic unreason’. The OED defines one sense of ‘unreason’ as ‘that which is contrary to, or devoid of, reason’, and furnishes two quotations for it, the second from the English philosopher John Grote: ‘That unreason or nonsense which it is the business of the higher part to convert into knowledge.’

Graves’s 1925 book Poetic Unreason condemns such conversion, and the ‘business of the higher part’, which it describes with chilly precision as ‘a system slowly deduced from the broadest and most impersonal analyses of cause and effect, capable always of empiric proof’.19 Producing knowledge from nonsense is a purely cognitive process that values the impersonal over the personal and the rational over the mythic, and effectively precludes poiesis. In the section of Poetic Unreason entitled ‘The illogical element in poetry’, Graves casts William Shakespeare, ‘the master poet’, as the antithesis of ‘conversion’, and his salient, determining feature is that he ‘insist[s] on his own absurd courses’.20

Graves clearly understands that he, himself, is behaving rationally, thinking clearly, writing logical discursive prose, but this apparent contradiction by no means upends his argument; it is only viewed as a flaw if one is being logical, and to judge his arguments against logic purely according to the laws of logic is to misjudge them completely. I would suggest that conundrums like these illustrate the complexity of ‘nonsense’ in Graves’s thought. Nonsense is not merely the freedom from or the opposite of sense, as proleptic thought is the opposite of deductive thinking, but a mode of perception, even a mode in which one can perceive nonsense and recognise its unique validity as an alternative epistemology to reason. Thus nonsense epitomises a structure of consciousness that can coexist with reason, and at least in one regard may be superior to reason, which can accept no other model for conscious intelligence than itself. One might even wonder if nonsense alone is able to discover meaning and value in both nonsense and reason, inasmuch as we have no logical, rational explanation for value, wonder, or romantic love. Appearing the same year as Poetic Unreason, Graves’s Welchman’s Hose begins with the poem ‘Alice’ and references Lewis Carroll’s Through the Looking-Glass. It is a poem D. N. G.

Carter insightfully discusses in Robert Graves: The Lasting Poetic Achievement. Extolling ‘the singular importance of children and the world of childhood in Graves’s poetry’, Carter writes that ‘Graves is not a poet of childhood in any regressive, de la Mareish sense, although he is, on occasion, a children’s poet: he has written for children, and children’s anthologies owe some of their better inclusions to him. Principally, however, he is interested in the child’s world for what it reveals about the adult’s’.21 Carter also adds, perceptively, that Graves’s ‘experience of childhood and children’ inform ‘the perceptions of his poems’, and that they are ‘as much a means of understanding life as are his more adult experiences in love and war’ (p. 145).

Carter’s book is the first to make the claim that ‘childhood and children’ are of singular importance to Graves – just, I would add, as they are to understanding Graves’s poetics. The defensiveness in Carter’s tone – for example, beginning with the negative exclamation, ‘Graves is not a poet of childhood’, and including a gratuitous and unfair deprecation of de la Mare – is an indication of the state of play. Before him, Graves’s critics had trod uneasily on this ground, just as Graves had done, if they trod at all. But in some key ways, Carter’s tentativeness and distancing distort Graves’s views. In particular, the hackneyed division of experience into the ‘child’s world’ and the ‘adult’s world’ imports oversimplified and discomforting ideas about childhood. While Graves does concede difference to children in ‘Babylon’, he tends more often to treat of phenomena with greater subtlety and complexity, eschewing metaphorical worlds for meticulous observation and reasoning.

The relevant distinction Graves does draw in ‘Alice’ is between the reality behind the mirror and the materially actual world of mid-Victorian England. In the poem bearing her name, Alice is never relegated to an existential children’s table, nor are her thoughts and perceptions characterised as childlike. She is defined specifically as ‘courageous’, ‘of a speculative bent’, set on fun, possessed of ‘British pride’ and of ‘uncommon sense’. She is also capable of sophisticated understandings despite the fact that she is a child:

For Alice though a child could understand

That neither did this chance-discovered land

Make nohow or contrariwise the clean Dull round of mid-Victorian routine,

Nor did Victoria’s golden rule extend Beyond the glass [. . .].

In the phrase ‘though a child’, Graves seems to be subverting the same generalisations about children he is invoking, just as Carroll had done, which are uncritically and perhaps inadvertently reinscribed in Carter’s analysis. Alice astutely observes that the usual physical laws do not apply in this ‘chance-discovered land’, and her ‘uncommon sense’ prevents her from falling into ‘A trap in which the scientist would fall’ by assuming ‘That queens and kittens are identical’.

The trap is spurious deductive reasoning. There is no basis on which one might assert that reason has any explanatory power in the world behind the mirror, the world discovered, and perhaps also governed, by chance and not causality. The Red Queen’s apparent metamorphosis back into Kitten can only dictate that queens and kittens are identical if one tosses aside the rest of the story. By contrast with disempowered reason, Alice’s ‘uncommon sense’ is exemplary, and the rare agency intrinsically linked to Alice’s unique personhood by whose authority Graves, or the poem’s Gravesian persona, capriciously abandons his narrative at line 33 to conjecture (with the garrulousness of Alice herself) that

‘this chance-discovered land’ is the very same land

Where empty hearses turn about; thereafter

Begins that lubberland of dream and laughter,

The red-and-white-flower-spangled hedge, the grass

Where Apuleius pastured his Gold Ass,

Where young Gargantua made whole holiday . . . .

However whimsical the tone, the reference to Apuleius is pointed and effective. In Poetic Unreason Graves uses Apuleius’s pasturage as an emblem of poetic unreason: ‘In Poetry one is continually straying into the bounds of a Thessaly like the land Apuleius celebrated, where magic is supreme and where, therefore, things happen which realistically minded strangers find difficult to understand’ (p. 125). Explicitly, by the authority of Apuleius (and implicitly, by that of individual taste), Graves celebrates the universality of Alice’s ‘lubberland’, and Alice’s personhood.22 By association he seems also to be implying that his own nursery rhymes are sanctioned by personal taste. After all, Shakespeare is not the paradigmatic master poet because he pursues absurd courses merely, but because he pursues his own absurd courses. For himself, Graves found the absurd course of nonsense and nursery rhyme.

A fascination with childhood and with children’s texts is evident in Graves’s choice of material, a choice that might appear childishly oppositional – evoking Georgian nostalgia only to abandon it for ‘epistemology in a mock-solemn vein’ (Carter, p. 147). His notions of childhood are likewise original: he evokes conventional ideals of childhood but subverts them by stressing Alice’s individuality. She is not Blake’s every child, but child and adult blended together, neither child nor adult, but, as the poem makes plain by declaring that she is ‘the prime heroine of the nation’, the unimprovable original. By refusing to relativise Alice, Graves circumvents a static representation of the child as an icon, as Judith Plotz writes, ‘of fixity rather than growth or change’, a social construction the Victorians had taken from the Romantics.23

This dull, static figure, whether Blake’s piper or James Barrie’s Peter Pan, and its concomitant cultural binaries such as ‘world of the child’ and the ‘adult world’, are the exact verities that ‘Alice’ destabilises. The (bad) scientist might assume that ironclad physical laws serve to describe or even determine essential correspondences; despite their apparent differences, ironically, Alice knows better.

Carter’s sensitivity to Graves’s engagement with childhood seems to fail him, although not his sympathetic grasp of Graves’s purpose, when he declares ‘the child’s world is also the artist’s’ (p. 147). These are artificial categories foreign to the poem, however proximate to Graves’s sentiment. An extraordinary child like Alice may enter the world ‘of dream and laughter’, but so might the readers of Apuleius and Rabelais; so might Graves and so might his readers, many of whom will be adults. As well as legitimising and validating children’s texts, ‘Alice’ offers the same opportunity for open-ended imaginative play to his readers, all of them, a point we take from Graves’s decision to make ‘Alice’ the first poem of Welchman’s Hose, and it was in the same spirit that he eventually published a selection of his poems as The Penny Fiddle: Poems for Children.

During the next thirty years Graves’s production of nursery rhymes seems to taper off, although he continues to write them in addition to nonsense rhymes, poems about childhood, children’s poems and poems inspired by children, in which childhood is a striking, salient element: [‘The Untidy Man’], ‘Lift-Boy’, ‘Brother’, ‘Flying Crooked’, ‘Parent to Children’, ‘The Beach’,

‘The Death Room’, ‘My Name and I’, ‘To Lucia at Birth’ and

‘Yes’, for example. In his essays, he continued to use children’s texts rhetorically, as though they were parables, to exemplify ideas and attitudes. He concludes his analysis of Milton’s L’Allegro, in a 1957 essay, ‘Legitimate Criticism of Poetry’, by drawing a surprising contrast between L’Allegro and two songs ‘of mirthful invocation’:24 one, Ariel’s song ‘Come Unto These Yellow Sands’ from The Tempest, I. 2, whose lines ‘Hark! Hark! [...] The watchdogs bark’ seem to echo the nursery rhyme ‘Hark, hark / The dogs do bark’,25 and the nursery rhyme, ‘Girls and boys, come out to play: / The moon doth shine as bright as day’ (p. 43). As well as reinforcing his reputation as a cranky iconoclast by this comparison, Graves reminded audiences of his unfaltering belief in the poetic artlessness of nursery rhyme, and asserted the pleasing complexity of nonsense by teasing out a reasonable, carefully organised, lively and cogent argument – though some may disagree with it or with its methodological principles – from an apparently nonsensical opinion.

Quoting Shakespeare, Graves is obliquely alluding to Milton’s own homage to Shakespeare in L’Allegro (‘Or sweetest

Shakespeare, Fancy’s child’), in effect agreeing with Milton that Shakespeare is the better poet. And, putting a further strain on what might generally be considered a legitimate use of criticism, Graves also implies that Milton had waived his right to object to his poem being ranked below ‘Girls and Boys Come Out to Play’ by his tribute to Shakespeare, particularly in its wording. Part of Graves’s fun peeks out from the margins of the joke. He has made Milton seem slightly absurd because of his use of the decorative conceit ‘Fancy’s child’, in which Milton apparently wanted to signify the imagination; but Graves, in preferring nursery verse to L’Allegro, presumes that he intended to signify something more like fantasticality (as in Shakespeare’s line from Love’s Labour’s Lost: ‘This childe of Fancie that Armado hight’), or personal taste (as he, Graves, is exhibiting in his tour de force of an absurd critique). Shakespeare, Milton, the author of ‘Boys and Girls Come Out to Play’ and he, himself, are all writing what comes nearest their fancy, and only personal taste has the right to tell us which is better.

I am merely suggesting that, with cunning and erudition, ‘Legitimate Criticism of Poetry’ repeats the argument of the superiority of nonsense to reason; for nonsense can simulate both the nonsensical and the reasonable, but reason can always only be reasonable. (The reason of L’Allegro melts away, but the nonsense remains: reason is a lossy technology, but nonsense, lossless.) Although, of course, Graves can be deadly serious about defending nonsense, in his critique of Milton his style is demonstrably tongue-in-cheek, even childish, modelling the freedom, disinterest and expressive range of poetic nonsense.

5 Pens in Hand also contains the children’s poem, ‘A Plea to Boys and Girls’:

You learned Lear’s Nonsense Rhymes by heart, not rote;

You learned Pope’s Iliad by rote, not heart;

These terms should be distinguished if you quote

My verses, children – keep them poles apart – And call the man a liar who says I wrote

All that I wrote in love, for love of art.

Graves unabashedly associates his poems with nonsense – modestly according them the same stature as Edward Lear’s (as Eliot had not done in his 1933 Five-Finger Exercises). Despite being addressed to children, ‘A Plea to Boys and Girls’ is nonetheless somewhat liminal, in that young readers could not be expected to have a sharp sense of either romantic love or autotelic art, thus depriving the final line of force; and, while adults could make the distinction, the allusions to memorising Pope and Lear would seem strained to them, as would the idea of learning

Graves’s poems by heart.

But if we count children the more plausible audience, then we might consider that Graves gendered the poem’s title, not merely to echo the nursery rhyme he praised in his critique of Milton (and which he had included in The Less Familiar Nursery Rhymes (1927),26 but to symbolise the importance of romantic love, in contravention of the norms of children’s publishing. While he omitted ‘A Plea to Boys and Girls’ from The Penny Fiddle, published only two years later, Graves incorporated three

(melancholy) love poems, ‘One Hard Look’, ‘The Hills of May’ and ‘Love Without Hope’. We might account for their exquisite, idiosyncratic presence by the implicit claim in ‘A Plea to Boys and Girls’ that one must recognise the unique importance of love in any discussion of poetry, at any level. And we might see the relationship here of romantic love and children’s poetry as a later, more elegant version of the relationship Graves had earlier proposed to Marsh between ‘spiritual feeling’ and nonsense, thus once again bringing nonsense under the auspices of the White Goddess.

Given Graves’s history and predilections, the publication of a book of poems for children in 1960 was hardly nostalgic indulgence, though surely in some personal sense it did enact a return. If it is the realisation of his earlier project of 1917–20, which should help to persuade us that Graves’s original inspiration was not commercial, The Penny Fiddle nonetheless embodies attitudes about childhood and children that would still seem progressive today, and ideas about reading and writing poetry that could serve to illustrate arguments he was making in lectures and essays published during this period in The Crowning Privilege and the Oxford Addresses on Poetry.27

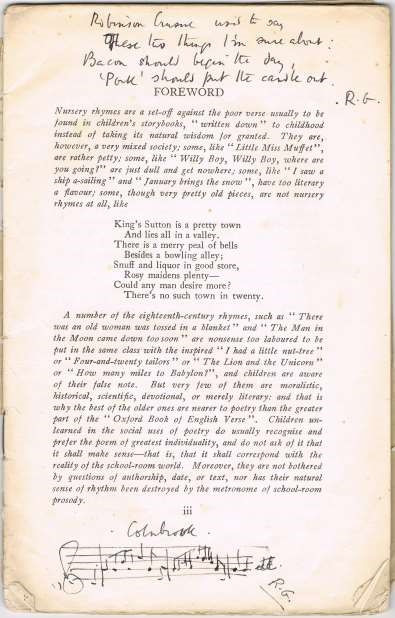

One of the features of the 1960 Penny Fiddle that distinguishes it from a simple poetic sampler compiled by a doting older poet for young readers is Graves’s scrupulous re-working, as noted by Dunstan Ward, of earlier poems, ‘Robinson Crusoe’, ‘The Six

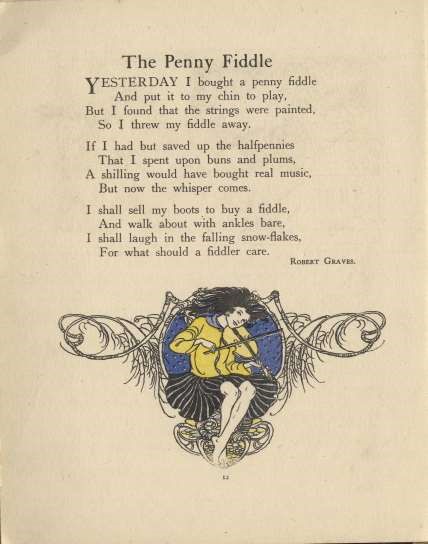

Badgers’, and ‘Jock o’ Binnorie’ (Collected Poems, III, pp. 439– 41). William Graves remembers his father used to ‘sing/recite’ verses from ‘Robinson Crusoe’ to him as a child, enunciating ‘pork’ with a little gust of breath that, as the lyrics say, would blow the candle out (see figure 2).28 In an email to the Canadian poet JonArno Lawson, Tomas Graves, the dedicatee of The Penny Fiddle, said he felt his father’s ‘interest in children’s poetry was more of a literary than a family matter’.29 Graves also made minor, and temporary, alterations to ‘What Did I Dream’, and composed an entirely new poem, ‘How and Why’. He radically reconceptualised the title poem of the volume to articulate a philosophical premise that serves as a key to the entire sequence of twenty-three poems. In the poem’s earlier version, published in Collins’ Children’s Annual in 1926 (figure 3), the narrator is a jolly young would-be musician who discovers that his fiddleshaped toy will not make music and tosses it aside, vowing that he will save up his money to buy a real fiddle, and even, if need be, sell his boots and go barefoot in the snow.30

The revision introduces a second character, a poor (penniless) girl,31 who picks up the rejected toy and teases music from its painted strings, at which the boy sighs, longing to have it back. He has no thought of the money he will spend on a real fiddle – paradoxically, the toy is real – ‘But, alas, she would not let it go’. In the magical fiddle, the revised poem enacts a transvaluation in which the materially worthless thing is also, simultaneously, the sacred. Like the penny fiddle, a children’s poem can be both the medium of true, ethereal music and still only a toy. Unlike the mock-heroic figure in the younger work, this melancholy boy is not inspired by art but by a mysterious process with a powerful sensual component. The music (and by association, the music of the poem), functions as a synecdoche. The mock-heroic boy, with thoughts of plums and buns and fiddlers who care not for the falling snow, is quintessentially a child, with the world view of a child. Although the boy of the later poem is also a child, longing has darkened his view. His childhood has unobtrusively ended. (This understated aspect of the poem is strengthened and recontextualised by the second poem in the volume, ‘Allie’, with its sweetly obvious, heartrending symbol of an April sunset – while the mysterious Gypsy girl, and the boy’s longing, reoccur transformed in ‘The Hills of May’, the twelfth poem.)

Fig. 2

Graves’s manuscript additions to his copy of The Less Familiar Nursery Rhymes (1927) (William Graves collection)

Fig. 3

First publication of ‘The Penny Fiddle’, Collins’ Children’s Annual (1926)

The wistful music of the poem’s final line of anapestic trimeter – ‘But, alas, she would not let it go’ – directs the reader’s attention toward the last line of Blake’s ‘Pretty Rose Tree’: ‘And her thorns were my only delight’, placing the two poems in virtual dialogue.32 (If children memorised Pope and Lear then, surely, they knew Blake.) While introducing the work in hand, ‘The Penny Fiddle’ also introduces the ekphrastic element of poetry, modelling its capacity to bring together poems separated by time and space to engage in a mutual interpretation of symbolic structures and meanings – a kind of creative hermeneutics. As well as performing a Gravesian interpretation of ‘Pretty Rose Tree’, ‘The Penny Fiddle’ holds itself open to a Blakean interpretation.

‘Warning to Children’, a 1929 poem whose hard, objective and self-reflexive character is in the epistemological vein of ‘Alice’ also signals that in 1960 Graves had something up his sleeve with The Penny Fiddle. By passing over more obviously childlike poems, such as ‘I’d Love to Be a Fairy’s Child’ and ‘Cherry Time’, and making ‘Warning to Children’ the volume’s concluding poem, and thus perhaps a dialectical counterpoint to ‘The Penny Fiddle’, Graves establishes the sequence within a discursive context that recognises certain principles of Romanticism and properties of myth. In Poetic Unreason, he claimed that nonsense – or ‘so-called nonsense’ – and myth were consubstantial, and, along with Romanticism, were equally despised: ‘Romanticism [...] has long been banished to the nursery [...] the one place where there is an audience not too sophisticated to appreciate ancient myths and so-called nonsense rhymes of greater or lesser antiquity’ (p. 126).

It would be a tricky argument to make that Graves composed ‘Warning to Children’ solely with an unsophisticated audience in mind, in spite of its title, and yet he might have expected children to respond to the music and apparent nonsense of it while being agreeably tickled by its elusiveness, as adults are. Two years earlier, Graves had argued for the full status of nursery rhymes as poems in the introduction to The Less Familiar Nursery Rhymes, declaring ‘the best of the older nursery rhymes are nearer to poetry than the greater part of the Oxford Book of English Verse’ (p. 13). Cannot we infer that in 1929 Graves also believed children were full-status readers, certainly capable of appreciating myths and ‘nonsense rhymes of [. . . ] lesser antiquity’, just as he was, better than the greater part of the adult population? And in 1960, embroiled in a public campaign against, variously, modernists or modernism,33 or the literary establishment,34 that he hoped to drive home that point in the form of a children’s book that contained some of his best and most complicated poems? That in this period he considered youth essential to poetry he makes clear in his essay ‘Sweeney Among the Blackbirds’, twice quoting by way of illustration this stanza from a poem by the sixteenth century poet, Thomas Vaux:

For Reason me denies

This youthful, idle rhyme And day by day to me she cries:

‘Leave off these toys in time!’

Siding with the young, with children, Graves would symbolically have been asserting his bona fides as a poet.

The progress of Graves’s nursery rhymes toward greater philosophic complexity (from ‘Babylon’ to ‘Warning to Children’) coincides with his retreat from Georgianism. One can see its genesis in a letter to Marsh of 17 December 1921, in which Graves defends another difficult poem, ‘The Feather Bed’: ‘You acknowledge that there is passion and spirit in my new writing, but you can’t catch the drift’. He also rebuts a charge Marsh laid against the poem, of being a freak of fancy, stating, ‘there is no harm in freaks of fancy if they are subtly related to a constructive purpose’. Answering what we infer to have been Marsh’s objections to the manic persona of the ‘Feather Bed’, Graves concedes that he ‘thinks in extravagant & apparently irrelevant pictures, but always they have a reference & a bearing force on the trouble at hand’.35

The phrase ‘thinks in extravagant & apparently irrelevant pictures’ suggests a metaphorical bridge or at least a point of comparison between the apparent irrelevancy of nonsense and the poem ‘In Broken Images’, which appears alongside ‘Warning to Children’ in Poems 1929.36

‘In Broken Images’ found no favour with Douglas Day, the first critic to produce a book-length study of Graves’s poetry, who thought its ‘total abstraction’ was ‘uncharacteristic of Graves’, and dismissed it as a ‘slight poem’, a charge often levelled at Graves’s nursery rhymes.37 Although no one has ever deemed ‘In Broken Images’ to be a nursery rhyme, it has certain features in common with nursery rhymes. Its binary form (which Graves revisited in other poems, such as ‘Despite and Still’, ‘The Portrait’, and ‘My Name and I’) proliferates in nursery rhymes, such as ‘Jack and

Jill’, ‘The Lion and the Unicorn’, and many lesser known rhymes:

Margery Mutton-pie and Johnny Bo-Peep

They met together in Gracechurch Street; In and out, in and out, over the way,

Oh, said Johnny, it’s chop-nose day.38

One’s immediate impression of ‘total abstraction’ is challenged by a sense of irony – or a cow-jumped-over-the-moon logic – that inheres in ‘In Broken Images’. Although the sceptical narrator who contrasts himself with the facile, self-confident, and notably silent, other, seems satisfied with the self-flattering distinctions he draws, the distinctions seem to fall apart before the formal unities of the poem. Seeming to mimic the ‘him-and-me’ binary, each stanza consists of two paired lines,39 and each line is similarly an end-stopped independent clause posited in the form of a mathematical statement. The initial stanza expresses a thesis and antithesis, which every succeeding stanza develops and reiterates:

He is quick, thinking in clear images; I am slow, thinking in broken images.

He becomes dull, trusting to his clear images;

I become sharp, mistrusting my broken images,

The poem marches along in lockstep like this until it appears to arrive at an obvious and predetermined conclusion in a last laconic stanza:

He in a new confusion of his understanding; I in a new understanding of my confusion.

If one overlooks the fuzziness of the poem’s logic, which teeters on the brink of, if not plunging into the heart of, nonsense, and sees it only as a clever contrast of the sort Graves had made in Poetic Unreason, then, no doubt, Day would be justified in his dismissal. However, the matching lines, spare vocabulary (a device that might remind us of the epitaph of ‘Interlude’), metrical and phonological similarities knit the distinctions into a ritualised and highly artificial call and response, so that even as semantic difference exerts a centrifugal force through the rational elements of the poem, pulling the nucleus of the poem apart, the syntactic, intuitive, musical, associations centripetally hold it together.

Although ‘In Broken Images’ seems to declare, A not B, it also posits an overriding co-identification, which the final chiasmus clarifies: A and B: mirror opposites.40

One might suggest that the poem invites a double reading: one clear reading trained on the logic of the text (Day’s disappointed pure or ‘total abstraction’), and a broken reading that instances a kind of ‘strange loop’,41 where musical correspondences at variance to narrative contradictions set the poem revolving in place, a version of the dynamic of ‘Warning to Children’, and a type of poetic nonsense.

In On English Poetry, Graves shares his poetic strategy in language that, for our own purposes, is as notable as the concept:

The underlying associations of each word in a poem form close combinations of emotion unexpressed by the bare verbal pattern. In this way the poet may be compared with a father piecing together a picture-block puzzle for his children. He surprises them at last by turning over the completed picture, and showing them that by the act of assembling the scattered parts of ‘Red Riding Hood with the Basket of Food’ he has all the while been building up unnoticed underneath another scene of the tragedy – ‘The Wolf eating the Grandmother’. (p. 24)

Fuzzy logic is also a determining element of ‘Warning to Children’, but beneath its fuzzy surface there is a keener and more obvious argument against abstraction, taking the form of a reductio ad absurdum of the rationalist proposition in Peter Markie’s ‘Rationalism vs. Empiricism’ that ‘our concepts and knowledge are [inherent and] gained independently of sense experience’.42

Peter Markie further notes that rationalists ‘argue that there are cases where the content of our concepts or knowledge outstrips the information that sense experience can provide’.

The unmediated abstraction in ‘In Broken Images’ eventuates in a thin, back of the napkin analysis. In ‘Warning to Children’ unmediated rationality perpetuates itself in an infinite regress as the mind endlessly performs the same unvarying, meaningless act, repetitively understanding a universe constituted by the same familiar, albeit mysterious, understanding:

Children, leave the string alone! For who dares undo the parcel

Finds himself at once inside it,

On the island, in the fruit,

Blocks of slate about his head,

Finds himself enclosed by dappled

Green and red, enclosed by yellow

Tawny nets, enclosed by black

And white acres of dominoes, With the same brown paper parcel Still unopened on his knee.

Of course, children can resist rationality no longer than they can resist growing up (like the songbirds of ‘Babylon’), but perhaps they need not be entirely defenceless; ‘Warning to Children’ models an alternative to rationalism in the illogical or magical factor that inhabits the poem’s playful humour, drumming rhythms and luminous contradictions (‘greatness, rareness, muchness / Fewness’), the factor that makes poetry coherent. Like the reason of the rationalists, the poetic is not posited as a function of language or art, or the poet’s heightened awareness, or beliefs, but as the super-sensory and primary. It is, once again, ‘the land

Apuleius celebrated, where magic is supreme’.43

The anti-philosophical argument of ‘Warning to Children’ is repeated in other poems in The Penny Fiddle, such as ‘The Magical Picture’, which criticises empiricism, the epistemological twin to rationalism. Again, in broad terms, empiricists develop accounts of the information on which knowledge is based. Markie writes that empiricists believe ‘if experience cannot provide the concept or knowledge the rationalists cite, then we don’t have them’.44

‘The Magical Picture’, the nineteenth poem in The Penny Fiddle, asks to be read as a warning against empiricism. The broken mirror ‘glinting on the roadway’, with which the poem begins, serves as a metaphor of experience – the empiricists’ ‘given’. The mirror is discovered by four characters: Tom (a child), his parents (Jack, a sailor, and Mary) and a priest, who peer into it and take the visions they behold of their own hopes and fears for knowledge of objective reality. The child perceives a scary goblin, Jack, a portrait of Admiral Nelson in his dashing youth, and Mary, the seductive lover of her possibly adulterous, seafaring husband. The pompous priest discovers ‘a saint of glory’ in it and decrees the broken mirror to be an icon.

While for empiricists sense experience is our only source of ideas, ‘The Magical Picture’ casts experience qua what the broken mirror offers as hermeneutically empty, and the knowledge we supposedly derive from it, sheer fantasy. What is lacking in ‘The Magical Mirror’ world is warrant,45 some mechanism to adjudicate upon the sensory data and perceptions generated by the mirror, which it cannot provide. Trusting the mirror for knowledge places us at the mercy of our own – and each other’s – fantasies, or nightmares.

Graves obviously liked this notion and made a similar comment in ‘A Child’s Nightmare’, an earlier, harsher poem published in Fairies and Fusiliers, later suppressed. Although not included in The Penny Fiddle sequence, ‘A Child’s Nightmare’ can shed light on its structure and on the underlying meanings of ‘The Magical Picture’. While Kersnowski discusses it at length, arguing very persuasively that Graves’s war trauma was mediated by the recollected terrors of childhood, it is, I think, an incomplete analysis, focused almost exclusively on the external circumstances of the poem at the expense of the poem’s structures and poetic content. In the narrative, a wounded soldier recalls the memory of a childhood dream in which a mysterious figure stands at his bedside repeating the word ‘cat’. Like Poe’s dismal raven, the monosyllabic utterance awakens nameless terror, which Graves calls nonsense:

But there’s a Nonsense that can keep

Horror bristling round the head, When a voice cruel and flat

Says forever, ‘Cat! … Cat! … Cat!’

Although in a very different tone, the voice ‘cruel and flat’ and the broken mirror of ‘The Magical Picture’ symbolise one and the same thing: the incomprehensible source of a steady, never-ending current of trivial information, or nonsense (in the worst sense). One might read finality or death into the unwavering presence of the voice, but I suggest it may be more precisely grasped as emptiness, a lack of revelation, the blanket meaninglessness of life and death. The voice is a symbol that denies the explanatory power of its symbolism, a token of a type it repudiates and hence a category error, which is an analogue to the broken mirror that neither reflects what is before it, nor provides illumination. It is a mirror without true mirroring properties: hence it is figuratively as well as literally a broken mirror.

The rationalist charge against empiricism, ‘no empirical lesson about how things are can warrant such knowledge of how they ought to be’,46 might also serve as the poem’s epigram. To warrant knowledge about how things ought to be requires an instrument of revelation, epitomised in The Penny Fiddle as the child’s toy fiddle, or, perhaps more particularly, the toy fiddle in the hands of the ironically inconsequential Gypsy girl: the materially valueless thing from which absolute value flows. If the music of the penny fiddle is poetry, then the only truth is poetic truth.

One further complexity of ‘A Magical Picture’ is the problem of the status or truth value of our interpretation of the poem. The magical picture (that is, what each character sees in the mirror) signifies the poem itself: directly, by name, as well as analogically. If what the zany characters think they see when they gaze at the magical picture is unreliable and abets self deception, then so might what we think we understand when we read ‘The Magical Picture’. Confoundingly, the poem seems to skip off the dissecting table. By cautioning us to view with scepticism our understanding of the poem, as merely another object within the category of empirical data, it points out the dissembling nature of experience and the unavailability of rational truth. The magical picture before our eyes beguiles (frightens, emboldens, seduces, humbles, mocks) us all.

Read in isolation, ‘The Magical Picture’ might be understood to be making the point Marianne Moore articulates in the poem ‘New York’: ‘One must stand outside and laugh / since to go in is to be lost’.47 However, in the context of The Penny Fiddle, the exemplary, enigmatic ‘The Penny Fiddle’ provides a different and I think more satisfying solution. The penny fiddle points us toward the transpersonal object of poetic vision, or what is intended by the ritualised act of music, or writing poetry, namely poetic truth. In 1959, Graves told Huw P. Wheldon ‘I think of poetic truth, which is what I am trying to get, as quite distinct from historic truth or scientific truth or any sort of rational truth. It is a sort of supra-rational truth’.48 When Wheldon asks if poetic truth is not religious, Graves replies, ‘it comes very close to the natural faith of religion’, which recalls his comment to Marsh forty-two years earlier about ‘the true spiritual feeling of [his] nonsense’, and brings together nonsense (or his ‘so-called nonsense’) with suprarational truth.

Supra-rational truth rescued ‘In Broken Images’ from the charge of total abstraction, and it also illuminates a second, doubled, reading of ‘A Child’s Nightmare’. Readers must infer from a basic reading of the poem that, as far as truth value is concerned, experience is a dead end, a bruising insult to the human quest for meaning, as I suggested above. It is merely ‘Nonsense that can keep / [the] Horror [of an aimless, painful life] bristling round the head’. However, its doubled reading amalgamates the poem’s specific insight, having been taken in at a first reading, and contemplates it within the context of the poem; it then makes us aware that insight, a qualitatively different kind of experience, can be expressed in exactly the same language as ‘Nonsense that can keep / Horror bristling round the head’. The ‘Horror’ in this sense depends from Rudolph Otto’s characterisation of the numinous in Das Heilige, as the mysterium tremendum et fascinans, which entails ‘the feeling of terror’, ‘awe’, ‘and religious fear before the fascinating mystery [. . .] in which perfection of being flowers’.49 We have an example of the tremendum of course in Graves’s quite similar description of what occurs in the presence of a true poem: ‘the hairs stand on end, the skin crawls and a shiver runs down the spine’.50 Horror bristles ‘round the head’ in ‘A Child’s Nightmare’ because one’s hairs stand on end, and because revealed truth is supra-rational, a truth above the head. Graves demonstrates the paradoxical capacity of poetic truth to co-exist within the radically different quiddity of experience by combining two essentially incompatible meanings into the same poetic lines: A and B.

So, keeping this idea of a non-Aristotelian ontology, we can conclude our analysis of ‘The Magical Picture’ by arguing that whereas the apprehensions of the zany personalities are fundamentally in error, being purely subjective experiences guided by a flawed epistemology, our apprehensions about ‘The Magical Picture’, informed by the paradoxical caveat that one should mistrust one’s apprehensions, are legitimate, grounded in experience though they are, because they are guided by the epistemology of poetic truth. Poetic truth frees us from the paralysing effect of ‘The Magical Picture’. The penny fiddle of course is another, more poetically self-conscious paradoxical symbol, and the guiding wisdom of The Penny Fiddle by which all of the poems in the volume are illuminated. Graves leaves no doubt about this ‘higher’ purpose by making it the first poem in the volume, and privileging its title as the volume’s title.

The three poems from The Penny Fiddle I have been discussing,

‘The Penny Fiddle’, ‘Warning to Children’, and ‘The Magical Picture’, share the unusual characteristic of objectifying the experience of reading the poem. Reading places one inside of the poem (looking, untying, playing are all variations on the theme of reading) and one’s impressions of the poem become part of its hermeneutic deposit. Becoming aware of this aspect, one enters into a dynamic process of poetic oscillation, in which analysis vibrates back and forth between discourse and meta-discourse, almost seeming, I think, an exemplification of how to read.51 Because The Penny Fiddle plucks these poems from various corners of Graves’s oeuvre and brings them into meaningful proximity – under, as it were, the sign of the magical fiddle (a Gravesian inversion of the classical lyre, symbol of Apollonian poetry) – it calls attention to this dynamic heuristically, also calling attention to its dependence on the reader’s performance of the text, which it further suggests is a linchpin to a mindful and visceral understanding of poetry.

Thus, on the most basic, childlike level, reading The Penny Fiddle functions as a game: making meanings from the oscillating poem creates vibrations from the invisible strings of the imaginary fiddle. On a more sophisticated, but no less childlike level, understanding the operation of the metaphor critically and valuing it in accordance with the argument and inhering myth of the poem ‘The Penny Fiddle’, depends on recognising that the collection recursively gestures toward itself, toward the reader, toward the plasticity and encyclopedic inclusiveness of poetry, and toward poetic truth. All of these elements vibrate simultaneously. Just as poetic truth surpasses the form and fiction of any individual poem, and any single (limiting) interpretation, it surpasses this or any other limited sequence of poems, and, hence contextualises the invocation here of other poems and poets: William Blake’s ‘Pretty Rose Tree’, de la Mare’s ‘Melmillo’ in ‘Allie’, Hamlet in ‘The Forbidden Play’, Macbeth and Lear in ‘Jock o’Binnorie’;

Coleridge’s ‘Work Without Hope’ in ‘Love Without Hope’52 and Donne’s ‘The Sunne Rising’ in ‘What Did I Dream’. By placing his own lyrics within this fertile, unruly matrix, Graves seems to be suggesting, to wise children, that the final warrant of poetic truth is the immanent and transcendent spirit of English poetry.

Rutgers University, New Jersey.

NOTES

1

‘The children’s stunt’ is a slightly obsolete and perhaps misleading locution. The term now carries the implication of a ‘gimmick’, or ‘trickery’, but it is likely Graves meant something else. OED 1b gives one possible usage he might have picked up during the war: ‘An enterprise set on foot with the object of gaining reputation or signal advantage. In soldiers’ language often vaguely: an attack or advance, a “push”, “move”.’ There is the possibility as well that he had in mind

OED 1d: ‘In wider use, a piece of business, an act, enterprise, or exploit.’ In fact, Graves might have read the term recently in Edward Marsh’s Memoir of Rupert Brooke (1918), in which it occurs in a 1913 letter from Brooke to Marsh: ‘Then I do my pet boyish-modesty stunt and go

pink all over; and everyone thinks it too delightful’ (p. 98). Brooke is poking fun at the strangers he is meeting who seem mawkish in their praise for his poems, and perhaps, implicitly, at his own innocent gratitude of which he is slightly ashamed. Sassoon, to whom Graves is writing, had told him to man up in his poetry, and ‘stunt’ might have echoed Sassoon’s attitude or served to remind him that Rupert Brooke, himself, had similar boyish tendencies.

2

3

York Public Library. Frank Kersnowski cites this unpublished letter in The Early Poetry of Robert Graves. However, his paraphrase of this passage, ‘Graves was confident in the lasting value of poems he called “the Nursery Rhymes,” such as “Henry Was a Worthy King,” and “Careless Lady”’ (p. 103), slightly underplays Graves’s admiration although it highlights his originality. It may be originality or humility that moves Graves to suggest the nursery rhymes may be the best poems in the volume, but he does in fact say it.

4

Cassell, 1960). That children’s poetry in general, and the first Penny Fiddle in particular, possessed merely commercial interest for Graves is a commonly held attitude (one might call it a misconception), which tends to lean heavily on Graves’s letter of 18 May 1920 to the literary agents, James B. Pinker and Son, about the Penny Fiddle manuscript (Graves to E. Pinker, Berg Collection, New York Public Library). Unlike most of the surviving correspondence to Pinker, this particular letter runs to several pages and includes fascinatingly detailed instructions regarding the printing, illustration, musical settings and marketing of the volume. The financial aspect of publication is of considerable interest to Graves, and he unequivocally asserts: ‘it must come out by this Christmas, for urgent financial reasons’. Few of his business letters of this period show so much care for marketing; however, all of them possess a strong business orientation. They are, after all, business letters. And while they have a contribution to make, must we conclude from them that Graves wrote for purely business reasons? Besides, there is much more to this letter than marketing. None of Graves’s letters to Pinker show as much feeling for the preparation of a manuscript, and despite the imminent financial crisis he is facing,

Graves maintains a flexible determination to keep the manuscript as is. ‘The book to suit the publisher can, at a pinch, be lengthened or shortened by two or three rhymes, but we do not want to do this and do not want to be dictated to by the publishers about which rhymes shall go or stay’. Even in extremis, the integrity of the volume takes precedence over commercial viability.

5

Fine Pottery’, New York Times, 25 April 1982

<http://www.nytimes.com/1982/04/25/travel/200-years-of-finepottery.html?pagewanted=all> [accessed 4 October 2012].

The poem reads:

Friends of man, there are but three

The horse, the dog, the apple tree;

The docile horse, that draws the plough;

The faithful dog that barks ‘bow wow’; The apple tree with fruit for me As I will show you, here and now.

In Robert Graves: The Assault Heroic: 1895–1926 (London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1986), Richard Perceval Graves writes that during this period, Robert and Nancy were in ‘a world of their own at a tangent to the normal world’. He comments as well that Graves was happily writing ‘nursery rhymes, songs and ballads’, and that his songs made him ‘a great deal of money’ (p. 194).

6

7

Cape, 1929).

8

Flag’, now in the New York Public Library, the manuscript of the first Penny Fiddle has not been traced, and its full contents are a matter of conjecture, inference and guesswork.

10 Frank L. Kersnowski, The Early Poetry of Robert Graves: The Goddess Beckons (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2002), p. 89.

Country Sentiment contained seven of the twenty-three poems in the

1960 edition of The Penny Fiddle, two of which appeared previously in the first and second issues of The Owl (May and October 1919), with Nancy’s illustrations.

11

12

13

15

Marsh, 12 July 1917, Berg Collection, New York Public Library, In Broken Images: Selected Letters of Robert Graves 1914–1946, edited by Paul O’Prey (London: Hutchinson, 1942), p. 77.

16

17

Times, 14 September 2012

<http://www.nytimes.com/2012/09/16/magazine/stephen-burt-poetryscross-dressing-kingmaker.html?pagewanted=all> (para. 4 of 30) [accessed 4 October 2012].

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

Dogs Do Bark’ cited by the Opies in the Oxford Dictionary of Nursery

Rhymes (see note 38) is a song in Westminster Drollery (1672) called ‘A

Dialogue between a man (in Garrison) and his wife (with her company) Storming without’. However, the parodic nature of the droll song suggests the possible existence of an earlier model, now presumably lost: one which, perhaps, Shakespeare expected his audience to know. Graves might have known the popular version, and expected his audience to as well, and thus appears indirectly to be reminding them of the authority as well as antiquity of nursery rhyme.

26

27

28

29

31

32

33

U.I.C.A., Washington, February 17th, 1958’, in Food for Centaurs: Stories Talks, Critical Studies, Poems (New York: Doubleday, 1960), pp. 97–119 (pp. 104–08).

35

36

‘Welsh Incident’ and ‘Wm. Brazier’, almost an anti-nursery rhyme, but also with a nursery rhyme flavour.

37

38

39

Poems 1929 the poem is not divided into stanzas, which first appear in Poems 1926–1930’. There may be many explanations for breaking the poem into stanzas, and one would be that Graves came to realise that couplets would emphasise the interdependence of the two characters and reinforce the impression of recursiveness.

40

121).

41

42

Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Summer 2012 Edition), ed. by Edward N. Zalta <http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/sum2012/entries/rationalismempiricism/> [accessed 3 October 2012]. 43 Poetic Unreason, p. 125. 44 ‘Rationalism vs. Empiricism’.

45 I am using a specialised definition of ‘warrant’ relevant to epistemology studies. Knowing a particular proposition, or accepting that a particular proposition is true, requires not only that we believe it and that it be true, but also something that distinguishes knowing from a lucky guess, that authorises it as knowledge. This something is known as a ‘warrant’. See Markie, ibid. 46 Ibid.

47

60.

48

University Press of Mississippi, 1989), p. 55.

49

50

51

52