|

Search Help |

|

Links Robert Graves Website Other RG Resources |

Obituaries

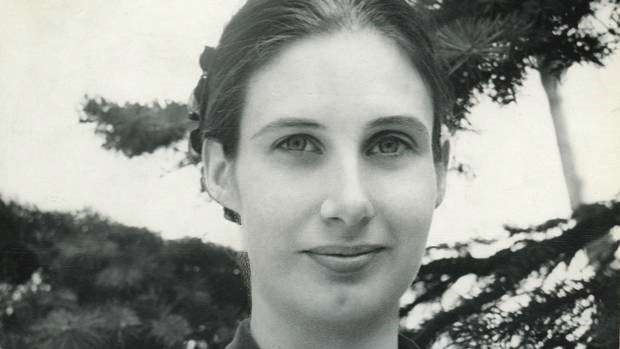

'An Immensely Happy Time': Robert Graves Remembered by Jay Macpherson (1931-2012)

Eighteen months before her death in March 2012, the distinguished Canadian poet and scholar Jay Macpherson made a return visit to Mallorca, where in 1952 she had met Robert Graves, who so admired her poems that he published her first book himself under his Seizin Press imprint.

It was William Graves who suggested at the end of January 2010 that I should try and persuade Professor Macpherson to come to the Tenth Robert Graves Conference in Palma and Deyá that July. ‘She was in Deyá on and off from the early to the late 1950s,’ he wrote. ‘I’ve never seen a copy of Nineteen Poems. I think only she and Terence Hards were given the honour of a Seizin publication.’

I had once spoken briefly with this almost legendary figure, at the Robert Graves Centenary Conference at Oxford in 1995, when Beryl Graves introduced us. Now I wrote to the University of Toronto inviting her to take part in a poetry reading at the conference in Mallorca. I also said that William and I were wondering if she might be prepared to give an interview, in which she could talk about her relationship with Robert Graves and his work.

Jay Macpherson’s email reply came two days later:

Monday 8 February 2010

Well, yes, tentatively--that is, I have commitments to a sick friend whom I can’t leave without some difficult arranging; but had been hoping to do just that for at least a bit of this summer. And you might not be so flattering if you knew me: poetry reading no problem (though I’m a long-dead poet--thought I’d done my last reading some 20 years ago), but I’m a terrible interviewee. Remember that amazing Irishwoman [sic: Honor Wyatt] who spoke at the first conference at St. John’s? think antipodes--I’m a writer, not a talker, and as I get older I struggle more and more to find words and remember things when I need them.

So--what do you think? --My very best to William: I think of him a lot more often than he might guess.

Regards, jm.

I answered at once:

We’d love to hear you read your poetry. As for the ‘interview’, I’m sure we can find a congenial format. What about a conversation with William over a glass or two of Mallorcan wine? With advance notice of some at least of the topics (if that would be helpful)?

Do come if you possibly can!

Which prompted:

Hi Dunstan--In my case it had better be grape juice. Discuss the rest later? j.

Nearly three months passed, and I was beginning to give up hope when I received her confirmation:

Hello Dunstan-- Well, looks as if I could get away (sorry to say this so late: life has been over-full): about to visit a travel agent, also send off the conference registration form. I haven’t seen a schedule of the conference program yet--starting the Tuesday morning? or evening? Not sure when you expect people to arrive, esp. people subject to jetlag. And ending the Sat. eve.? Wd appreciate any guidance (am still distracted: this weekend is deadline for article with very snaggy footnotes). Cheers- j.

I sent her details of the conference, recommending the hotel where a number of us would be staying, and explaining the format of the poetry reading:

Regarding the conference programme, I am delighted that you are happy to take part in the poetry reading, during which the poets are invited to speak briefly about their relationship with Robert Graves and his work; to read several poems by Robert Graves that have a particular appeal to them personally; and then to read a selection of their own poetry. The reading lasts about an hour and a half, which gives each poet about 20– 30 minutes. It will be held on Friday 9 July, at the end of the afternoon, followed by the main conference dinner.

I added:

On further reflection (and given your reservations) I feel that to have an ‘interview’ (or such) as well would perhaps be redundant. What do you think?

Jay Macpherson agreed: ‘Happy to skip interview, if that suits you. j.’ Soon afterwards she sent me the list of Robert Graves poems she was ‘staking’ – ‘just so we don’t all go for the same ones’.

On the first morning of the conference I found Jay Macpherson sitting alone at her breakfast table in the courtyard of our hotel, a shabbily splendid sixteenth century palace. Slight, elderly, with straight silver-grey hair, she had kept a youthful quality. Her manner was both direct and reserved. I found her immediately likeable, if a little daunting, and we took to breakfasting together. I mentioned that Beryl would have been pleased by the inclusion of her third poem, ‘The Devil at Berry Pomeroy’, a favourite. She talked quite readily of her visits to Mallorca, of her friendship with Robert Graves. To a twenty-yearold had he, I wondered, seemed ‘formidable’? Not at all, apparently.

She returned to my question in her talk at the poetry reading. As usual, the poets were invited to speak in alphabetical order: Grevel Lindop, Michael Longley, and finally Jay Macpherson:

Since 1940, when my mother took her children overseas, I have lived in Canada; but when I was twenty, just graduated from college, I spent a year with my father in what had been the family house in Well Walk, Hampstead, sitting in on lectures at UC London. During that year a friend showed some of my poems to Robert, and he wrote to me; we corresponded all that winter, and he invited me to come and stay during the spring vacation, 1952. Then in June the family came to London for a few weeks and stayed in Church Row, just a couple of streets away from Well Walk: Beryl was pregnant with Tomas and not feeling very well, and I hooked on as child-walker and laundress and such, and also ran around with them or him on various errands and social calls. After that year I went back to Canada and my connection with them was sporadic – I stayed in Deyá a couple more times, and spent time with Beryl in Oxford at the time of the first of these conferences.

Someone asked me today if I found Robert formidable. No, never for a moment – long before we met he had taken me on as so to speak one of the clan, and I found him very warm, very open, full of jokes and songs and stories – very easy to be with. I used to sit all day in the workroom, plugging away at a book-length translation job, while Robert worked at the Penguin myth-book with occasional consultations with Janet de

Glanville, Beryl sat elsewhere over a translation from Spanish – El Sombrero de Tres Picos? – or working at Russian (I think that was then), while Martin Seymour-Smith, Jan’s other half, tutored the children. About four o’clock we used to go down to the cove to swim, usually just Robert and I; evenings were less predictable, and I don’t remember them clearly. We also spent a night or two in the flat at Guillermo Massot.

For me it was an immensely happy time. I had good friends in Canada with whom I could talk about poetry and mythology and such, but I’d spent far too little time, ever, with people who were happily married, and

Robert and Beryl were very much that – even though the first Muse, Judith Bledsoe, had already made her appearance. (Robert characteristically had me mythologised into her complement – I think active to her passive? I tried to arrange to meet her on my way through

Paris, but she didn’t answer my letter.)

I want to say something about Beryl. She was the one I at first found formidable: she had a very cool style, analytic where Robert was intuitive, and I much feared I might be found wanting; but so far from sitting in judgment she was enormously tolerant, and I soon became comfortable with her too. And I very much admired her ability to respond with grace and kindness to whatever might turn up, while keeping the whole situation anchored. It’s my recollection – not a factual memory but a strong impression from the time – that Robert’s poem

‘Rhea’, which he placed last but one in his 1957 Penguin selected poems, took its rise from an afternoon in Church Row when she was less in command: a thunderstorm was darkening the out-of-doors and cooping the children up in that small flat – Beryl was lying down with the door closed but both the thunder and the kids roaring up and down – ‘On her shut lids the lightning flickers, / Thunder explodes above her bed…’

And, my last moment with Robert at the end of that springtime visit. He was seeing me off at the ferry to Barcelona – I’d climbed onto the bottom rung of a passenger barricade to hug him and kiss his cheek: he muttered, ‘I must give you something,’ and felt in his pockets and pressed a matchbook into my hand – that impulse was so like him! I kept my matchbook with pebbles from Deyá for years and years.

Jay Macpherson’s choice of Robert Graves’s poems for her reading was an intriguing one:

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

It was moving to hear her read in Mallorca these poems by Robert Graves which evidently spoke particularly to her, and then her own poetry, which he had encouraged her to write and for which he had been her mentor.

When the conference was over and Jay Macpherson was back in Toronto, I urged her to expand her brief talk into a longer memoir for publication in the book of the conference proceedings, but after several setbacks she eventually wrote:

13 September 2011

Sorry, Dunstan, this isn’t going to work. My photo of RG has faded too much to be decently reproducible--the pictures my mother took of me at that age don’t come to hand--and I no longer have a copy of ‘Nineteen Poems,’ the pamphlet Robert published--nor would I want to resurrect that now. All the best, and I’m really sorry to disappoint you. j.

Her last email to me, like her first, reflected a lifelong concern for others:

29 October 2011

I’m just fine--in Hamilton, Ont., at my annual 18th-cent. conference-reading tomorrow (1st time since Palma) at somebody’s fundraiser (‘terrorist’ about to be deported on v. flimsy evidence, meantime being billed for police surveillance charges, would you believe it?)--all the best, Jay.

Later in the year Jay Macpherson began suffering from serious back pain; she was eventually persuaded to seek medical treatment, and was diagnosed with cancer. She died at the age of 80, surrounded by friends and family, on 21 March 2012.

She leaves her niece and two nephews.

THE ISLAND

No man alone an island: we Stand circled with a lapping sea. I break the ring and let you go:

Above my head the waters flow.

Look inward, love, and no more sea,

No death, no change, eternity

Lapped round us like a crystal wall To island, and that island all.

Jean (Jay) Macpherson was born in London on 13 June 1931. Her mother sailed with her and her younger brother on the dangerous convoy route to St John’s, Newfoundland, in 1940 as ‘war guests’. The children were each placed in separate Canadian families. It was four years before Jay rejoined her mother and brother; her parents remained apart after the war ended.

Jay Macpherson studied at Carleton University, McGill University, and at Victoria College, University of Toronto, where she was a student of the great scholar and critic Northrop Frye, who was to be a crucial influence.

Frye met her at a restaurant ‘as he was escaping a meeting’, Macpherson wrote subsequently. After a brief conversation they parted ‘with the offer ringing in my head that if I could get myself to Toronto he would ‘teach me

Blake’ – by myself, as he wasn’t otherwise giving the course’.

Frye supervised both her Masters (1955) and PhD (1964) in Victorian literature, and she became one of his closest friends and colleagues, teaching English at Victoria College from 1957 to 1996; she was appointed Professor of English in 1974. Frye once recorded in his diary: ‘Whenever I’m with Jay I realize that her level of perception is higher than mine: I’m more short-sighted, but it’s the mental patterns she creates out of her livelier mind that make the difference.’

Jay Macpherson began publishing poetry in 1949. After reading some of her early poems, Robert Graves wrote to James Reeves on 7 June 1951:

There’s a new woman poet in Canada called Jay Macdonald or Macgregor – I forget the clan. Aged 21 and spends her holidays with a friend of ours called Greta [...]. I tried to find something wrong with her poems but could not; you know how grudging I am of praise, but these were the real thing, though from Canada. Greta says that she’s brilliant at Classics, hates Canada, is utterly lonely and also beautiful: what troubles lie ahead for that girl! I think of Laura.1

Her first book, Nineteen Poems (1952), was published as a twenty-first birthday present by Graves’s Seizin Press, and her second, O Earth Return (1954), by her own small press, Emblem Books. The two volumes were incorporated into The Boatman (1957, expanded 1968), which established her reputation and received the Governor General’s Award for poetry (she was too shy to attend the public ceremony to accept it in person). Dedicated to Northrop Frye and his wife, Helen, The Boatman is a cycle of lyrics unified by symbols of fall and redemption, and reflects Frye’s engagement with mythical and archetypal elements in poetry. It contains a sequence about Noah and the ark, which ends with ‘The Anagogic Man’, a poem that is said to have come to her as she watched Frye approach the entrance to Victoria College one day:

Noah walks with head bent down;

For between his nape and crown He carries, balancing with care, A golden bubble round and rare.

Its gently shimmering sides surround

All us and our worlds, and bound Art and life, and wit and sense, Innocence and experience.

The major American literary critic Harold Bloom was immediately struck by the title poem of The Boatman. ‘She was a woman of the deepest literary sensibility and really very close to a kind of genius in poetry and in deep meditative thought upon the meaning and nature of poetry,’ he said in an interview, in which he recited several of her poems by heart. Bloom included her as one of only two Canadians – the other was her close friend and former student Margaret Atwood – in American Women Poets (1986).

Jay Macpherson’s other major collection, Welcoming Disaster (1974), maintains imaginative involvement with social realities while extending her essential concern with psychological and metaphysical themes. The Boatman and Welcoming Disaster were reprinted together with other poems as Poems Twice Told (1981), which Harold Bloom listed in the brief Canadian section of The Western Canon: The Books and School of the Ages.

She also wrote protest songs; and from 1954 to 1963 she published the works of emerging Canadian poets in eight Emblem Books chapbooks.

Her scholarly work includes The Spirit of Solitude: Conventions and Continuities in Late Romance (1982), a highly-regarded study of the elegiac and pastoral traditions from the seventeenth century. With Northrop Frye she co-authored Biblical and Classical Myths: The Mythological Framework of Western Culture (2004), based on a course they taught jointly. She also published Four Ages of Man (1962), adaptations of classical myths for younger readers.

Colleagues at Victoria College wished to nominate Jay Macpherson for an honorary degree, but she considered she was ‘unworthy’. As Harold Bloom observed, if someone praised either her poetry or her scholarship she ‘just shook her head slightly with a very faint smile on her lips’.

Acknowledgements to Sandra Martin, Globe and Mail (Toronto).

1 Between Moon and Moon: Selected Letters of Robert Graves 1946–1972, ed. by Paul O’Prey (London: Hutchinson, 1984), pp. 96–97.