|

Search Help |

|

Links Robert Graves Website Other RG Resources |

Critical Studies

Laura Riding's Role in the Poetry of Robert Graves: A Case of 'Multiple Authorship'?

University of London Institute in Paris

Laura Riding pervades a substantial proportion of Robert Graves's poetry with her redoubtable presence — as Muse; as mentor; as collaborator; eventually, one might even say, as Nemesis .

In this article I am concerned primarily with her textual contributions to the poems, rather than with the influence of her thinking as such. It is not easy to determine just what elements in the philosophical content of Graves's poetry can be traced directly back to Riding. This has, of course, been the subject of controversy and polemic, much of it emanating from Riding personally. Nor have all of the excessive claims been made by Riding devotees. Even a Graves critic as generally judicious as Michael Kirkham could state in his 1969 study that during the four years from 1926 to 1929 Graves 'absorbed Laura Riding's ideas concerning the nature and function of poetry, the nature of the poetic self, life in society and human existence; he acquired in the process a new set of poetic and moral values [... l, a much clearer sense of purpose, and something like a Weltanschauung' (110). To call this exaggerated would be an understatement. Graves himself, after reading Kirkham's study, wrote to him in January 1969 that 'A good deal of Laura Riding's "influence" on me, and what she wrote in her books for all of which I underwrote the publication[,] was "feed-back"; we lived & worked together for thirteen years, so this is not surprising.' Riding was, he adds, 'only one of seven women [ .. .1 whose different influences have divided my work into recognizable periods of an average of seven years apiece.

] [Elach impress is clear and distinct'. l Certainly, for all the impact of Laura Riding's ideas and personality, the essential continuity in Graves's thinking and beliefs, and in his poetic practice from even his earliest work, has been convincingly demonstrated by Graves scholars, notably D. N. G. Carter.2

When one turns to textual 'influence' the problems by no means disappear, but at least there is more concrete evidence. Riding's presence in the poetry in a sense actually predates her irruption into his life on 2 January 1926, through the part she played in the preparation of his first volume of collected poems, Poems 1914—26, which involved eliminating all but 134 poems out of more than 280 published since 1911, and revising much of what was left (Complete Poems, I, 413—14). But it is in the 1938 Collected Poems that their 'close literary partnership', as Graves termed it (in Collected Poems (1914—1947) (xi)), is most apparent. In his diary Graves records how during the months from April to August 1938 he systematically went over all his poems with Riding and rewrote them in response to her criticisms and suggestions: 'Only about 10 poems have escaped [sic] revision', he noted on 4 August. They kept in just fortyone from the first collection; the book is twenty-six pages shorter and contains 144 poems, an increase of merely ten (Complete Poems, Il, 298).

Graves acknowledges in the 'Foreword' to Collected Poems (1938) Riding's 'constructive and detailed criticism of my poems in various stages of composition' (xxiv). During their 'partnership' he in fact submitted each of his poems to her as he wrote it, and thus Riding's textual interventions were both numerous and varied. They included: detailed comments on specific words and lines, and actual revisions — her annotations can be studied on many of the manuscripts; more general criticism of a poem (for example, on a typescript of 'Against Kind': 'I haven't gone on correcting this — because I don't think it's a sincere poem, especiall[y] as it goes on — a sort of duty-poem, its emotions not the same as your emotions' (Complete Poems, Il, 276) — Graves excluded it from the 1938 collection): incidentally, on the drafts some of these negative verdicts have been partially erased;3 deleting lines and stanzas altogether; and rejecting a poem or 'passing' one when she judged that it was in an acceptable state. Being 'passed' by Laura Riding seems to have been like a combination of a product getting through a technical inspection in a factory; a student earning a pass mark or grade; being granted the Roman Catholic censor's 'nihil obstat'; and making the ranks of the blessed at the Last Judgement. For there were those poems that not only failed the test but were condemned to destruction

'criticism' in its most radical form. Thus Graves reports in their newsletter

(Focus, 2 (February—March 1935), 15): 'As for work since last Focus [January 1935], I have written eight poems and destroyed three. Two of the survivors passed Laura's scrutiny without a singly [sic] query. This is a record' (Complete Poems, Il, 298). Or again, in his diary for 25 April 1938, when he was preparing the Collected Poems: 'Laura went over some early poems with me. At her suggestion I destroyed Easter Still' — a poem he had been composing over the past ten days.

Quite apart from the poems they wrote jointly, 'Midsummer Duet' and 'Majorcan Letter, 1935', the Graves—Riding 'partnership' would seem to constitute a classic case of what Jack Stillinger has called 'multiple authorship'. In his 1991 book Multiple Authorship and the Myth of Solitary Genius, one of the not-so-solitary geniuses is Keats: Stillinger analyses the texts of 'Sonnet to Sleep' and 'The Eve of St Agnes' to show the importance of the contributions made by the poet's friends and editors. He finds that the sonnet 'has at least three and sometimes as many as four or five authors', though 'Keats is of course responsible for the lion's share'. And he claims that 'such multiple authorship — the collaborative authorship of writings that we routinely consider the work of a single author — is quite common, and that instances much more extensive and more impressive than "Sonnet to Sleep" can be found virtually anywhere we care to look in English and American literature of the last two centuries' (22). Numerous instances might be expected, then, among the poems Graves wrote or rewrote during his years with Laura Riding. By examining Riding's annotations on drafts of individual poems one can gain some idea of the nature and extent of her textual collaboration, and so provide part of the basis for an assessment of its significance. I propose to look now at the drafts of

'To Evoke Posterity', first published in Collected Poems (1938), and reprinted nine times through to 1975. This is an astringent satire, one of those poems in the volume which effect, to quote the 'Foreword', an 'exorcism' of 'pretensions' by 'self-humbling honesties' (xiii). It was written in April 1937, while Graves and Riding were at Lugano, in Switzerland, where they stayed from February to June. They had gone there from England, having left Mallorca on 2 August 1936 after the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War. It was a difficult time for them, with disturbing news from Spain and worries about their friends back there. Graves registers his less than enthralled response to Switzerland and the Swiss in his poem 'Hotel Bed at Lugano', which he started on 10 April; on 15 April he complains in his diary, 'Only difference in days seems between what we get for supper.' The following day they heard that Oxford University Press had 'turned down' Riding's dictionary ' "as too individual & personal . . . words cannot be put into strait jackets." ' ('Another example of tolerance of illiteracy (for the sake of lexicographical richness)', comments Graves — a lifelong devourer of the Oxford English Dictionary — possibly for Riding's benefit.) Yet he was busy composing new poems. On 20 April he records 'Three drafts of a poem "To address Posterity["]', and the next day, 'Two more drafts of To Address Posterity, which L read & passed.' (He also mentions that Antigua, Penny, Puce 'has sold 2500 in about a month in U.S.A.' — not, one imagines, to the elation of Riding.)

Graves's lighter poems and his more serious ones, Carter declares, 'all alike share in the same concern — to define the nature of integrity' (14). The lightness of 'To Evoke Posterity' derives from a characteristic ironical poise, which enables it to make an all the more telling attack on poetic falsity, the betrayal of inner integrity for the sake of public status:

TO EVOKE POSTERITY

To evoke posterity

Is to weep on your own grave,

Ventriloquizing for the unborn:

'Would you were present in flesh, hero! What wreaths and junketings ! '

And the punishment is fixed:

To be found fully ancestral,

To be cast in bronze for a city square, To dribble green in times of rain And stain the pedestal.

Spiders in the spread beard;

A life proverbial

On clergy lips a-cackle; Eponymous institutes,

Their luckless architecture.

Two more dates of life and birth

For the hour of special study

From which all boys and girls of mettle Twice a week play truant And worn excuses try.

Alive, you have abhorred

The crowds on holiday

Jostling and whistling — yet would you air Your death-mask, smoothly lidded, Along the promenade?

Draft I

Draft 5

To Ad.apee•e PogteFi y

Is to weep . on your own grave, fie unborn:

'Would you were present in flesh, •hero,

What. vrreaths and junketinget

And the punishment ig

To be round fully

To be' cast, In bronze for a square; To dribble green vin times Of rain And stain the pedestal.

eard;

A life proverbial

T?jponymoug institutes ,

Atheir luckless architecture.

more atee of Ii$ an birth

t*or• he

vhieh all boys and a week play truant

Of

get

And worn excuses try.

avo growd con hdliday

Jostling and whistling?

Vour death—mask smoothly Walking

launt

Draft 6

Draft 7

Co evoke posterity

Is to weep on your own grave,

Ventriloqui ing for the unborn t FWöu1d you were present In flesh, hero, What wreaths and Junketings!

And the punishment Is known :

To be found fully ancestral,

To be cast In bronze for a city square, To dribble green In times of rain And stain the pedestal.

To be cast In bronze for a city square, To dribble green In times of rain And stain the pedestal.

Spiders in the spread beard;

A life •proverbial

On clergy lips a-cackle;

F,ponymous institutes,

Their luckless architecttre.

Two more dates of life and birth For the hour of special study

From which all boys and girls of mettle Twice a week play truant And worn excuses try.

The poise and detachment are much less evident in the early drafts, and to a considerable degree are the product of Graves's extraordinary gift for revision, plus Laura Riding's contributions.

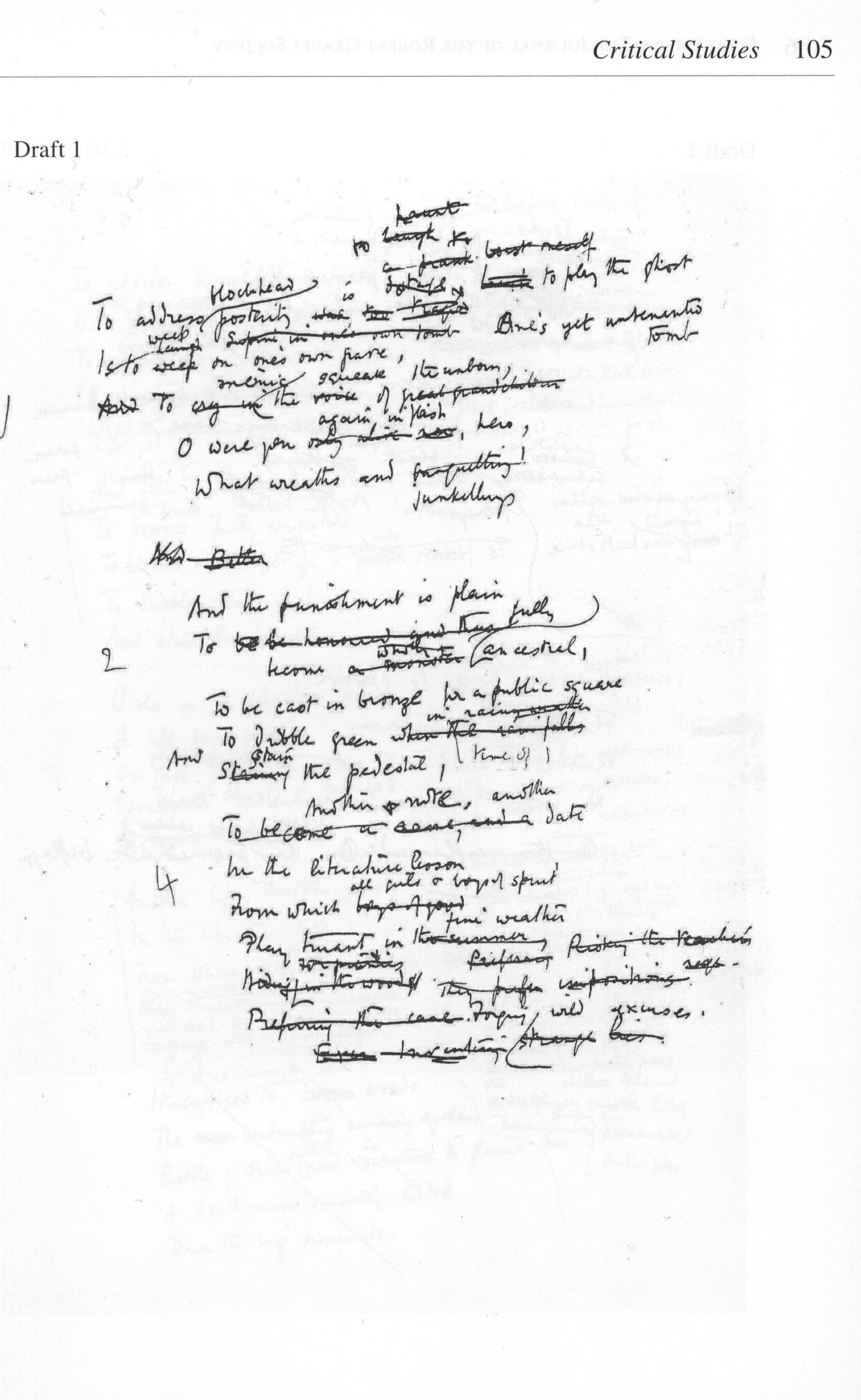

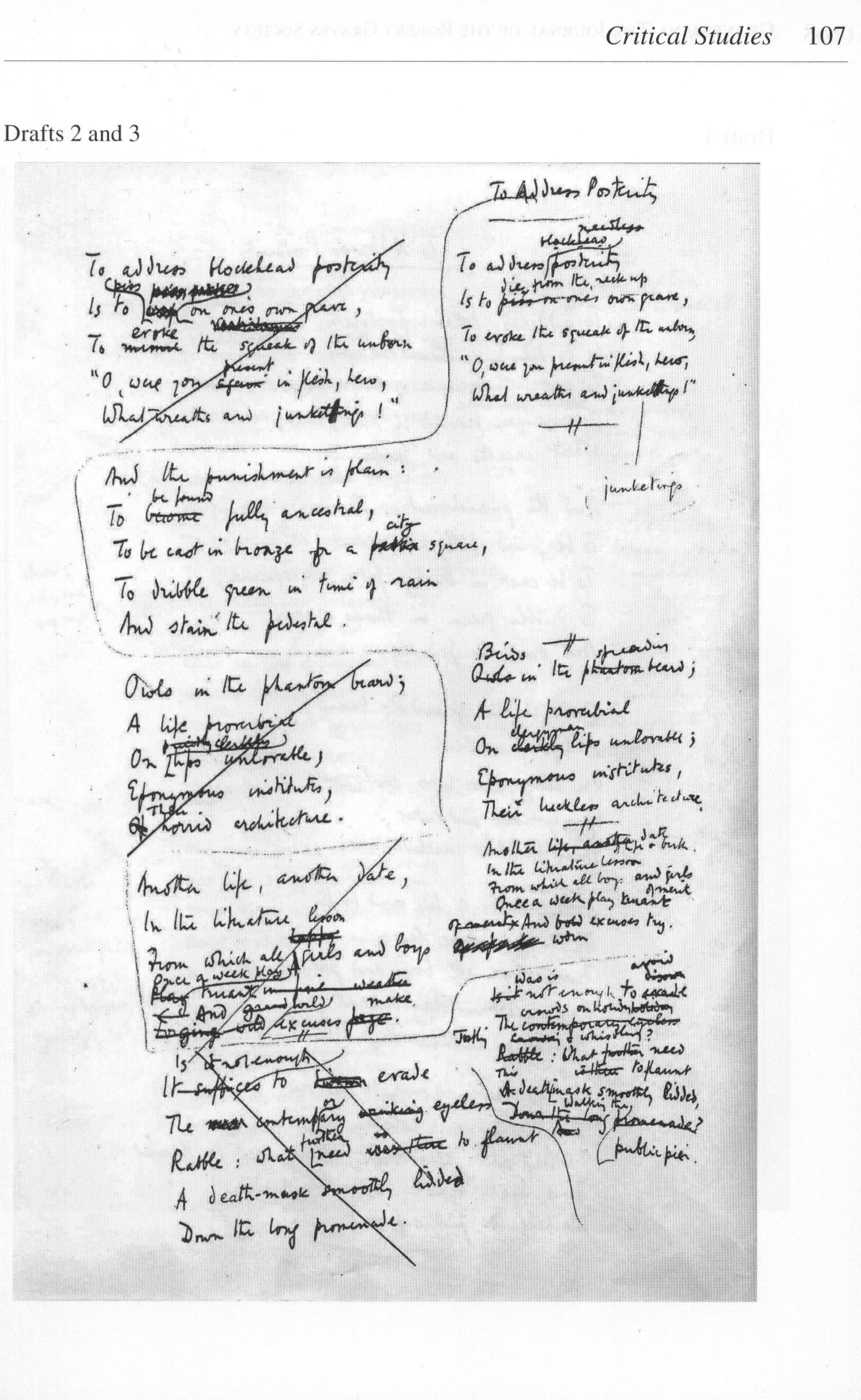

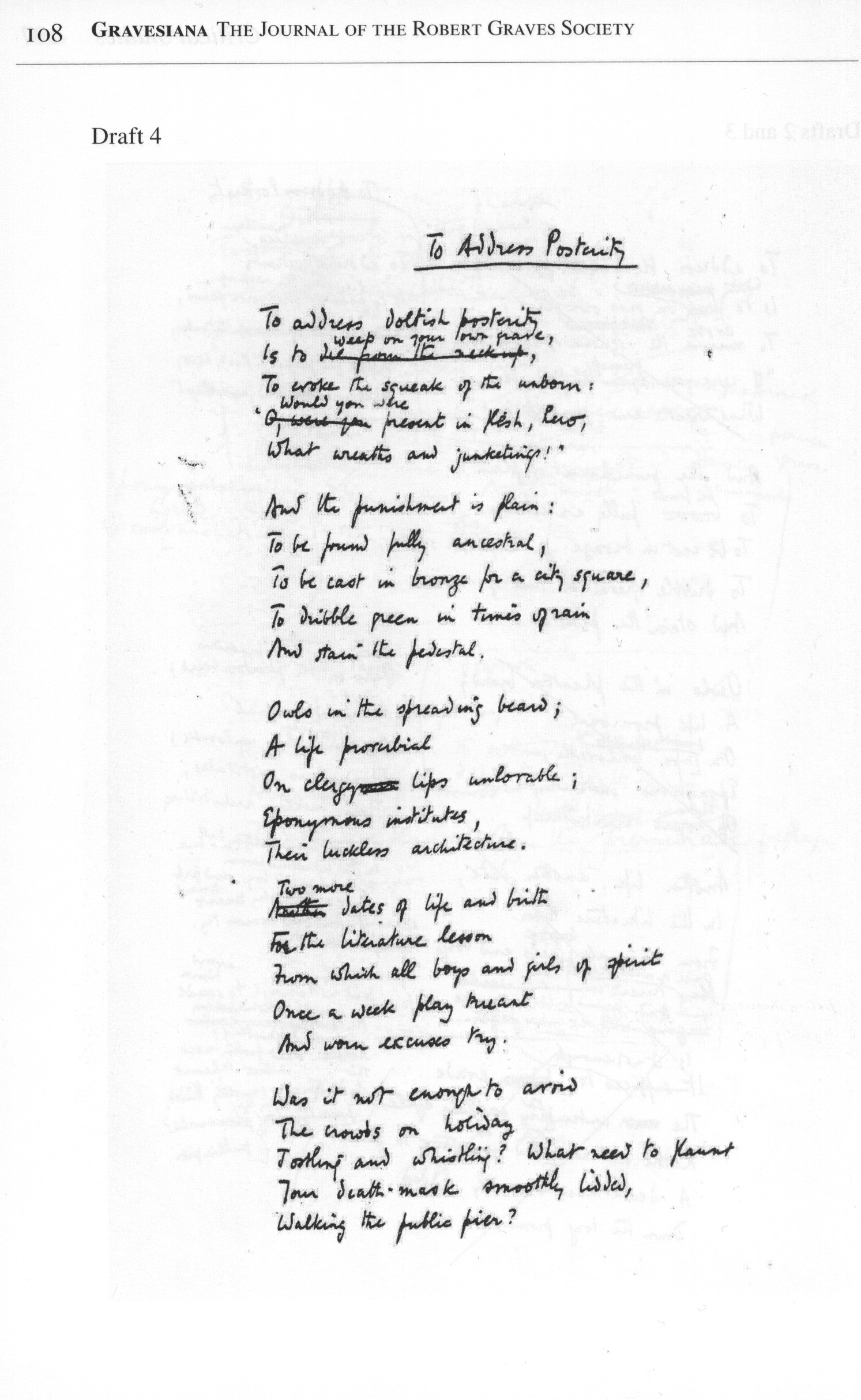

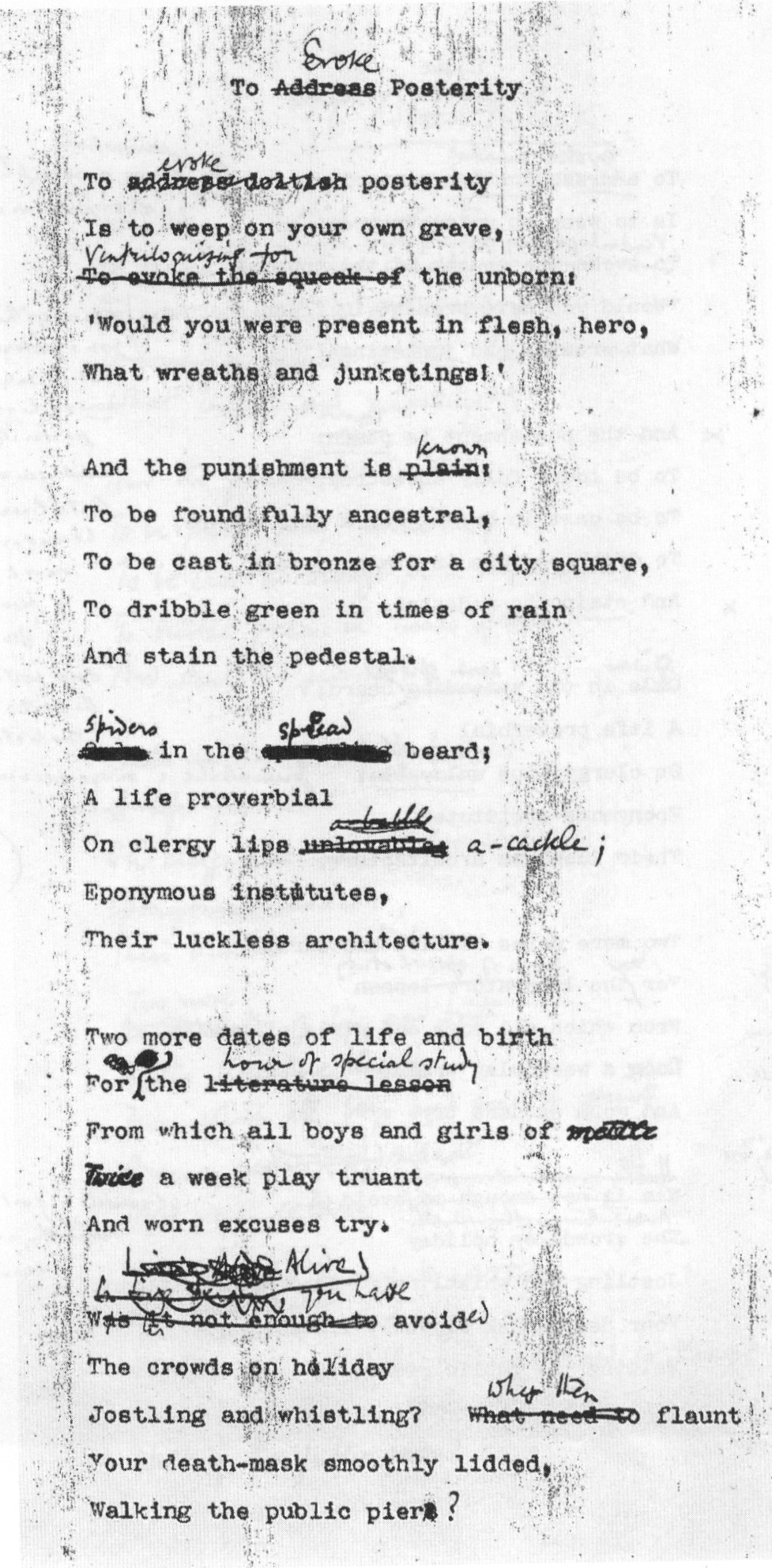

In the Poetry/Rare Books Collection at the State University of New York at Buffalo, there are seven drafts: four manuscript drafts, in ink, and three revised typescripts (see above). The version in the third typescript is that in Collected Poems (1938), whose wording differs from the last version in Collected Poems 1975 only in stanza 5 line 3, 'Yet you would air' becoming (from Collected Poems 1959) 'Yet would you air'. Riding's pencilled emendations and comments are on the first typescript, i.e. the fifth draft, in which the fourth manuscript draft has been typed out and then revised.

Most of the poem is already set down in draft l; there are no indications of any earlier draft (or drafts), though it is unusually clear and coherent in comparison with many of Graves's other first drafts. The stanzas have been numbered in the left-hand margin, with the third and fourth stanzas numbered so as to reverse their order. On the draft the poem, which is titleless, begins, 'To address blockhead posterity'; this was originally 'To address posterity was too tragic', then 'To address posterity is to play the ghost' (with 'dotage' and 'a prank' among the cancelled alternatives).

The title 'To Address Posterity' appears at the top of the third draft, which is written on the right-hand side of the same sheet as the second; 'blockhead' is replaced by 'needless' but then stetted. In the fourth manuscript draft (a near-fair copy, with revisions only in four lines), 'blockhead' becomes 'doltish' (scarcely more favourable): Laura Riding has underlined it in the next draft and commented 'journalistic', 'too easy assumption that post. is doltish'. Graves has cancelled 'doltish', also 'a wise' pencilled above it.

The finely paradoxical second line in stanza 1 was initially the same as in the final version, except for 'one's own grave' instead of 'your own' (as from the fourth draft), though there are alternatives above — 'Supine in one's own tomb' (cancelled) — and in the margin — 'One's yet untenanted tomb'; 'weep' is replaced by 'laugh', but restored. Then draft 2 takes up the imagery of the following stanza with 'Is to piss on one's own grave' (somewhat unGravesian), changed in draft 3 to 'die from the neck up'; Graves cancels this in draft 4 and interlines 'weep on your own grave'.

Stanza 1 line 3 begins (in draft l) as 'And to cry in the voice of great grandchildren', revised as 'To mimic the squeak of the unborn'. In the next draft 'mimic' is replaced by 'evoke', Graves thus removing a problem of logic: how can one mimic something one has not heard? Laura Riding has drawn a vertical line beside lines 4 and 5 in the fifth draft, ' "Would you were present in flesh, hero, / What wreaths and junketings!" ' and queried (down the righthand margin): 'Who says this — you = posterity? But the subject is now as hero to posterity — would you were', 'last 2 lines <can> will be read as what is said to post. because of "you" ' 'does post. squeak the last 2 lines? make clear', 'perhaps change address to evoke?'

The confusion does indeed arise from the ambiguous function of 'address' in line I — 'To address ] posterity ] : "Would you were present [. . . ] Graves accordingly has changed 'address' to 'evoke' in line 1 and in the title, and revised line 3, 'To evoke the squeak of the unborn', with inspired precision to 'Ventriloquizing for the unborn'. Incidentally, the nicely mocking 'junketings' appeared in place of 'banquetting' in the first draft.

The sardonic second stanza, which makes the bronze hero 'dribble green' and 'stain the pedestal' — a superb instance of Graves's emblematic imagination — needed few revisions after the first draft. Riding points out that 'plain' in line l, 'And the punishment is plain', creates a 'strong rhyme', and hence 'sympathy', with 'stain' in line 5. Graves therefore discards the relatively inert adjectival 'plain' for the verbal 'known' and — more trenchantly — 'fixed' (in Collected Poems (1914—1947)). In the second draft he similarly replaced the abstract 'become' in stanza 2 line 2 ('To become fully ancestral') with 'To be found fully ancestral' — which has a neatly punning relation to the next line, 'To be cast in bronze'.

Stanza 3's 'spiders', evincing neglect, appear in the web-like 'spread beard' only in the fifth draft: up to then they were 'owls' — a little incongruous, whether Athene-wise or Edward Lear-nonsensical — or (once) 'birds', and the beard 'phantom', then 'spreading'. In line 3, the 'clergy lips' were 'unlovable', which Riding has again rejected as 'journalistic', asking for 'more precise Characterization'. Graves has substituted 'a-babble', creating a near-rhyme link with 'proverbial' but also an over-supply of bilabial plosives, so in the next draft he makes it 'a-cackle', which 'architecture' then echoes (or cackles back). In draft 3 Graves himself had already replaced another 'journalistic' adjective, 'horrid architecture', with 'luckless', a stroke of genius, and an excellent example of the way Graves can continue the creative process during the revision phase of what he earlier termed, drawing on Freudian psychology, 'secondary elaboration'. For Kirkham the word is 'a buoyantly gay piece of understatement, typically expressive of Graves's "sanguine temperament" ' (151). The felicitous phrase 'Eponymous institutes' — it resounds with hollow pomposity — he came up with in the first draft.

In stanza 4, the 'Two more dates of life and birth' were previously not for

'the hour of special study' but 'the literature lesson'; Riding has underlined 'literature' and (curiously, given the poem's subject) put 'history', with a question mark, in the left-hand margin. In the fifth draft Graves has inserted 'For o, the literature lesson' (adding a stress), but Riding queries this: 'Why "o," — you don't quite get enough feeling ironic in here to justify "o" '; he deletes it. Graves also in draft 5 substitutes 'mettle' ('boys and girls of mettle') for the metaphysically- (or alcoholically-) connoted 'spirit' in previous drafts, 'mettle' picking up the sound-pattern in 'special' (line 2); and he boosts 'Once a week' to a doubly mettlesome 'Twice a week'.

In stanza 5, lines 1—3 first read 'It is one thing to disown / The <dark> raw contemporary / Rabble' — too crude an expression of distaste (like 'doltish posterity'): in draft 3 Graves tones it down to 'Was it not enough to avoid / The crowds on holiday / Jostling and whistling? / What need to flaunt / This deathmask smoothly lidded, / Walking the public pier?' Beside lines 1—3 Riding has commented (in draft 5), 'Crowds —jostling . . something not right about syntax here', and proposes: 'Do you not, alive, always avoid / The crowds [.. .1 ? Why then flaunt [. . . ] ? ' Graves adopts this more personal approach, and after various attempts he finally (in draft 7) hits on 'Alive, you have abhorred' — much more expressive than 'avoided', and recapturing, but more subtly, some of that initial disdain for the 'rabble'. A potential incongruity in the death-mask 'walking the public pier' (masks cannot walk) he stylishly dissolves in draft 7 with 'Yet you would air [instead of 'flaunt'] your death-mask smoothly lidded, / Along the promenade? ' 'promenade', salvaged from drafts I and 2, supplying a nearrhyme with 'abhorred' and 'lidded'.

What I think emerges from this analysis — and the poem is representative — is that Riding's role is editorial and critical, but not actually creative. The effect of her interventions is to draw Graves's attention to defects of the kind he himself has been identifying and dealing with: weaknesses in wording, awkward syntax, confusion in the poem's logic, problems of tone. It is he who then goes on with the revising, in order to concentrate, to enrich, to attain greater precision and clarity. Where the wording asserts, it is refined until it suggests, making the poem imaginatively 'evoke' rather than directly 'address'. It is Graves who provides the material itself; Riding's most significant revision, replacing 'address' with 'evoke', simply moves his word up a couple of lines — it is already there.

In short, Riding's contributions are valuable but not, I would suggest, crucial. I would argue, moreover, that such editorial and critical contributions are not authorial, and that Stillinger's term 'multiple authorship' is misleading. While Stillinger persuasively demonstrates the need for 'a more realistic account of the ways in which literature is created' (183) than that underlying the 'myth of solitary genius', it seems to me that he confuses the issue by conferring on a poet's friends, spouses, editors, critics, agents, publishers, and so on, the status of co-authors, even if they do happen, as in the case of Riding (or Pound — though not in Graves's opinion), also to be poets themselves.

That said, Stillinger's work, as he himself shows, has important theoretical and practical implications for the editing of literary texts, and specifically for editing Robert Graves's poetry. Stillinger argues for 'a theory of versions' as being 'most compatible' with what he calls 'the facts of multiple authorship'. This 'theory of versions' is 'based on the idea that every separate version of a work has its own legitimacy'. He rejects the aspiration of the Greg—Bowers 'theory of copy-text' to produce 'in a single text combining early accidentals and late substantives, the Platonically perfect realization of an author's final intentions in a work', on the grounds that it results in ' "ideal" texts that never previously existed', which seem 'the realization of editors' rather than authors' intentions'. On the contrary, he quotes approvingly Donald Pizer's argument that each version of a text 'constitutes a distinctive work with its own aesthetic individuality and character', and that 'to coalesce these versions into an eclectic text and its apparatus is to blur the nature of each version' (197—200).

Needless to say, producing an edition that makes available in a non-hierarchical fashion all the versions of a text raises technical and practical questions. Stillinger himself found in Coleridge and Textual Instability: The Multiple Versions of the Major Poems (1994), where he presents his own 'practical theory of versions' (118—140), that he 'regrettably had to choose or construct a standard text' of each of the poems to refer to, and to assemble the variants in an apparatus; he admits that in the book he was thus 'both arguing strenuously against the single-text ideal and [... ] inevitably contributing to the reinforcement of just such an ideal' (26). (One reviewer complained, besides, that at times 'the state of the apparatus approaches the chaotic, if seen from the point of view of a reader wishing to reconstruct any particular version'.)4

Stillinger believes that, given 'the routine formats of scholarly editing' and of 'trade and textbook publication', 'there is no escaping this situation' (26). As for my own experience, when Beryl Graves and I set about editing the Complete Poems we opted for one version as the text (the last version, in accordance with Graves's own practice), recording in an apparatus at the back the omitted material and variants from the first book version (together with a selection of especially significant variants from other versions, both manuscript and printed). This was done precisely so as to avoid producing more of those ' "ideal" texts that never previously existed' (though incorporated into the last published version in our text are revisions that Graves made subsequently, in his library copies of his books, for example); and to make available two integral versions. Of course, we would have liked our publisher to print in full the first book version together with the last one, but this would have meant a parallel-text edition, and there was already enough for three volumes . . . .

Stillinger blames his predicament in Coleridge and Textual Instability on having to present his information 'linearly, on the flat pages of a printed book (instead of using some form of electronic spreadsheet or hypertext and distrib- uting the information via e-mail)' (26). Scholars and readers still want books; so do publishers and booksellers. The three-volume Carcanet edition of the Complete Poems, which was finished in 1999, and the 2000 single-volume edition (the same text, minus the apparatus and notes) republished in Penguin Classics in 2003, meet that demand. There is a need, however, for a full variorum, which I am now working on, and it seems clear that this has to be an electronic edition. Only in this form will it be possible to reproduce all the printed versions, without reducing the rest to variants and relegating them to an apparatus. And not just that: an electronic edition will also be able to include all the drafts of the poems, together with commentary and, where appropriate, transcription — of Riding's faint pencilled annotations, in particular. Thus the creative genius of Robert Graves will be observable 'on the wing', as he composes and revises each of his poems; and due credit may finally be given to Laura Riding for at least this aspect of her collaboration.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

For their help in the preparation of this article, originally a paper delivered at the 2000 International Robert Graves Conference at Buffalo, I am most grateful to Dr Robert Bertholf, Dr Michael Basinski and members of the staff of the Poetry/Rare Books Collection, SUNY at Buffalo.

WORKS CITED

Carter, D. N. G. Robert Graves: The Lasting Poetic Achievement. Basingstoke and London: Macmillan, 1989.

Graves, Robert. Poems (1914—26). London: Heinemann, 1927.

Collected Poems. London: Cassell, 1938.

Collected Poems (1914-1947). London: Cassell, 1948.

Collected Poems 1959. London: Cassell, 1959.

Collected Poems 1975. London: Cassell, 1975.

Complete Poems, Vols 1—111, ed. Beryl Graves and Dunstan Ward. Manchester:

Carcanet, 1995, 1997, 1999.

The Complete Poems in One Volume, ed. Beryl Graves and Dunstan Ward. Manchester: Carcanet, 2000.

The Complete Poems, ed. Beryl Graves and Dunstan Ward. London: Penguin Classics, 2003.

Diary, February 1935—May 1939. University Library, University of Victoria, British Columbia, Canada.

Kirkham, Michael. The Poetry of Robert Graves. London: Athlone Press, 1969. Stillinger, Jack. Multiple Authorship and the Myth of Solitary Genius. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1991.

Coleridge and Textual Instability: The Multiple Versions of the Major Poems. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1994.

NOTES

1.

2.

3.

4.