|

Search Help |

|

Links Robert Graves Website Other RG Resources |

Biographical Studies

Memories of Robert

Guy Cooper, an author, landscape gardener and BBC television presenter, first met Robert at the age of 17 in 1952. In 1999, he set out to write a memoir recalling his friendship with the Robert Graves and his family. He showed a draft to Lucia Graves who suggested that he might ask some of the friends who had shared the various houses that Robert and Beryl had lent to him over the years to add their impressions to his account.

What follows here is a fascinating series of personal recollections of life with Robert, his family and three of the Muses edited and collected by Guy Cooper. (ed.)

For Beryl Graves: My Memories of Robert Guy Cooper

1952

In the middle of the summer term when I was at Clifton College my father agreed that being seventeen I could go abroad for the first time on my own. A girl whom I knew in Bristol had just come back from Mallorca where she had spent her honeymoon and had said it was quite wonderful and very cheap which was important, as we were only allowed to take E25 for foreign holidays in that year.

I decided to go with a school friend and one day casually mentioned it to another contemporary called Roger Cooper (no relation) who said, "if you're going to Mallorca you must meet uncle

Robert Graves;" his mother was Robert's sister. And so it all began.

In early July, I was in London and Roger introduced me to Robert and Beryl who were there for a few days. Robert said that they would be delighted to see me if I was in Deya, and if I was coming could I telephone his publisher and bring a document with me to the island. This was the first, but not the last of many requests.

David Hooker and I arrived on the island in late August, and after a few days in Palma caught a very old bus to Deya. The road was very winding and it seemed to take a long time between leaving Palma and catching the first glimpse of the sea below the cliffs on the north coast. A little while later we rounded the curve of the mountain and I saw the village of Deya for the first time, with the hill in the middle, and the church on top. We found a little pension in the upper village and went that afternoon to Ca N' Alluny for the first time to meet Robert and Beryl and William, Lucia and Juan, and Robert's 'court' for that year.

The week that I spent in Deya was the most significant week in my adolescence, because it transformed me from a rather proper and very protected public school boy into a young adult. I was shown a glimpse of what the world could be like and how adventurous it could be. I don't remember all the people who were there, but they included the editor of Time magazine and his wife, the Oxford Jazz Band (rusticated from Oxford), and their den mother Elsa Barker-Mill, a nervous English girl called Pamela, a rather drunken Hollywood film director called John Farrow, and his 16 year old English girlfriend, blonde with unbelievably long legs, called Lady Jane Vane-TempestStuart.

Many of the couples were obviously living together and having sex, which was something I had never come across before. I was intrigued and enthralled and knew that I had met a world of which I wanted to become a part.

I must have seen Robert and Beryl every day, usually for a drink in the evening, after a day on the beach, and to meet and remeet all the people of the circle. They were immediately very friendly towards me and on the 7th September, which was my 18th birthday, Beryl organised a picnic lunch for the family and one or two friends, which we had in the pine woods between the Cala and Llucalcari. The Cala is the principal beach of Deya, which is about 2 kilometres from the village. To reach it there was a very windy road suitable for horse and cart but not for other vehicles at that time. The other, and more usual route, was to descend through the terraces planted with olive and lemon trees which made a much more interesting walk and took about half an hour .The next swimming spot was below the hamlet of Llucalcari which was about 1 1/2 kilometres from Deya. The swimming place was rocky with a single boat house and a rock 300 yards out to sea where Robert would collect sea salt for the family. It was at that picnic that Robert said that he and Beryl liked me, and that I was to let them know if I ever wanted to come back to Deya, because they would almost certainly have a cottage or house which they could let me have.

On my last night in Deya, John Farrow heard that neither David nor I had ever been drunk and he said that it was something everybody needed to do, and that I was to follow his instructions that evening. He asked what I drank, and I said glasses of white wine, and so in between these glasses he made me drink a variety of other alcohols: brandy, whiskey, liqueurs and I became very drunk for the first time in my life. Fortunately I had already said goodbye to Robert and Beryl because the following morning I had my first hangover, and had to go by taxi, train and bus from Deya to the Puerto de Pollensa which took 12 hours, and that journey remains in my mind as one of the most unpleasant 12 hours of my life up to that point. It did not stop me drinking, however.

During that week, John Farrow had also thrown Jane out of the hotel at Llucalcari where they had been staying, after he found her in bed with the third Spanish waiter. I was mightily amused the following year when our Queen was crowned, and that Jane was one of her maids-of -honour.

Interim:

In 1953, I went into the army for my National Service and then in 1955 to Cambridge. My only contact with the Graves family was Christmas cards.

1956

At Cambridge, we had a three and a half month summer vacation and I wrote to Robert in May to enquire whether or not a cottage might be available for that summer, and he wrote back saying that there was one-half of a fisherman's cottage just above the Cala available for E4 a month. I drove down at the end of June with my college roommate Jeremy Hogben who became an architect and Andrew Bonar-Law whose grandfather had been the Prime Minister. We arrived at Palma on the morning of the 3rd July and drove to Deya, stopping at Ca N' Alluny to introduce ourselves and to be told the route to the fisherman's cottage. We were warned that it was only just possible to drive down the road. We descended through olive trees and lemon groves, opening and closing gates, stopping at a covered sheep hut, and for a moment thought that might be the cottage, but continued until the road stopped about 50 yards from a small paved area which overlooked the Cala, and on the right hand side was the fisherman's cottage.

In one half lived the fisherman, his wife, two sons and his daughter and the other half was the cottage in which I was to live for three and a half months. It had an entrada with a well in one corner, which was also the dining room, off it was a small sitting room and beyond that, a kitchen with a sink and two charcoal braziers. Upstairs were two bedrooms, one with a double bed and the other with two single beds. The 100 was about twenty yards away at the bottom of the garden, no running water, no electricity, no plumbing: idyllic.

Within half a day we re-organised furniture, hung a picture or two, decided which beds we were going to sleep in, and had taken the car back up the hill where we bought some flowers and felt completely at home. Robert and Beryl came down to see us that afternoon and were amazed by the transformation and our pleasure at being there. The fisherman's wife had agreed to produce supper each evening for however many people were staying, at the cost of 6 pesetas each. The

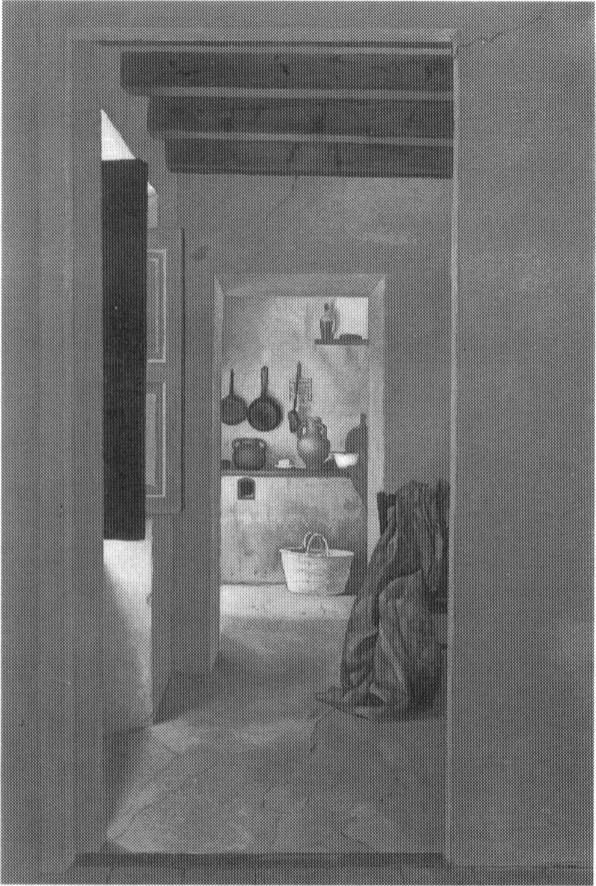

Painting of the interior of Guy Cooper's cottage by Mati Klarewin (reproduced with permission of the artist)

meal was usually soup or a little salad, a piece of fish and a potato, and whatever fruit was in season.

My father arrived the following day and met Robert and Beryl with whom he became extremely friendly, and he visited Deya regularly during the following years, whether I was there or not.

It was my first summer in the Mediterranean and more importantly it was the summer that I got to know Robert and his family. A sense of trust was established between us, and it took me only a very short time indeed to realise that I need not be at all in awe of Robert, so long as I was honest and truthful. He realised very soon that I was a practical person, and although I had an interest in the visual arts, architecture and literature, my appreciation of poetry and music were much more limited.

In all the years I knew him, he might mention a poem that he was working on but never discussed it in any detail with me. He would be more forthcoming about his prose projects, whether they be novels, biographies or works of historical research. I found the easiest time to talk with him was when we walked together to the beach at Llucalcari. It was his habit to go there at five in the afternoon, and it became mine, as I had to work during part of the day reading various law books, for I was changing my tripos studies from economics to law.

In retrospect, it could be an uncle/nephew relationship in which we felt at ease to talk about ideas and thoughts which young adults find more difficult to discuss with their parents. Sometimes, these could be of a very practical nature. I remember in Palma one morning Robert going into a tobacco kiosk in order to buy a box of matches. The woman assistant appeared to misunderstand almost deliberately what Robert wanted, and became both impatient and distracted. Robert politely said thank you, and left the kiosk and said to me "that there will always be occasions in life when you think you have clearly made your wishes understood, but you are not communicating in any way with the other person. On such occasions it is simpler and better to walk away unless it is the family, a friend or a lover!" Extremely practical advice which I have tried not to forget.

The summer was filled with many people from Cambridge coming to stay with me. Robert tended to treat all the men similarly, saying "who' s your father and what was your regiment?" and gently flirting with all the girls. A honeymoon couple came to stay at

Llucalcari, Robin and Brenda Bonham-Carter; they were an extremely attractive couple. I had been to school with Robin and would have been his best man had I not been on the island. There seemed to be quite a lot of visiting between the cottage and Ca N' Alluny during their stay and I remember giving my first proper dinner party in the cottage at that time. I had learnt to cook on the charcoal braziers, and I remember making chicken in white wine as the main course for that evening.

One day the family and I were in Palma when Ralph

Vaughan-Williams and his wife turned up for drinks in a cafe on the Borne where we all met that year. Robert and he were reminiscing about being at Charterhouse together and suddenly to the amazement of the rest of the clientele started singing the Charterhouse school song; a wonderful moment of two very distinguished men remembering school days.

I also helped produce the play for Robert's birthday that year. I don't remember what it was about, but I do remember that Robert loved it and afterwards we watched the fireworks drift across the valley below the house. I think Marnie Pomeroy, a wonderful statuesque American and John Foster-Dulles's niece, was in the show, and, I was certainly aided and abetted by the Scots poet, Alistair Reid, who was around all that summer. He became a good friend.

Towards the end of August, four great friends from

Cambridge arrived: Julia Cook, Thalia Dyson, Nick Younger and Francis Kinsman. Francis and I were supposed to be writing a libretto for a musical which never happened. Julia, who later married a judge, was slightly involved with Nick, and Thalia with no one, until one moonlit night, she decided I might be in the running. It was also Thalia who taught me how to cook and made me much more confident about the two charcoal braziers, and that started my obsession for cooking wherever I have lived or travelled or been ever since. We even got unofficially engaged for a few months, but that's another fabulous story.

To celebrate the end of their stay in the cottage we gave a party for eighty people i.e. all the Graveses and their hangers on, and other friends, except for those people Robert had made quite clear would not be 'acceptable' that year.

It started at seven in the evening when the party was divided into four, and there was a treasure hunt, which included finding a frog and an old Martini bottle (very difficult as the fisherman's wife had collected all the empties from the rubbish tip the day before to earn 10 céntimos.)

We didn't know this, so the party started with everybody dusty, slightly dirty and very thirsty. It never looked back. And after the food, the five of us gave a cabaret, which opened with the following song:

It's Cabaret Time in Deya

It really couldn't be gayer,

We're here to entertain you with an amateur display, The talent's mediocre, the material is worse.

As time was rather short we were unable to rehearse, But we are youthful and exuberant in a hearty sort of way

Ole! Ole! Ole! Ole! Ole!

So bear with us and share with us a little bit offun,

The lights have been put out, the show has practically begun,

Hold on to your hats and take your chances,

With Julia

Thalia

Guy

Nick

Tiddly, tiddly, and Francis

Some people left after the cabaret, but for the rest of the party the only entertainment was a wind-up gramophone for which there was one 45 record. On one side it was 'Three Coins in a Fountain' and on the other side it was 'Those Wedding Bells are Ringing Out That Old Gang of Mine'. One got to know those songs quite well as the moon rises and falls, and dawn comes up six hours later. It was an unforgettable party and some people who were in Deya at that time still say when they see me "do you remember that party at the cottage above the Cala?" Forty two years later, Thalia told me that she and her husband Max had written to Robert because they had decided they wished to spend their honeymoon in Deya and did so in the Posada in September 1960.

I had my 22nd birthday at the cottage, and five days later left the island having had one of the most extraordinary summers of my life, more memorable because I had made the change from being an acquaintance to being a friend of the Graves family.

1960

I didn't return to Deya until 1960 when I had already been working for Unilever for two years. I came with an old friend from Cambridge called Anne Snow, and there was no house for the first week, so we stayed in a little pension in the upper village and for the last two weeks were lent the Posada next door to the church. Here there was running water, a 100 and electricity for two hours of the evening. We didn't have a car until my father came out for some of the time. Lucia and William Graves were growing up. Juan was still a school boy, and Tomas was five or six. At one stage, I thought we might have gone to the cottage again because it was being lived in by an American who had been married to Aemilia Laraquen, called Cindy. My earliest memories of Cindy are comparatively vague except that one evening in the garden of a house somewhere in the lower village she was the first person ever to introduce me to marijuana. Robert and Cindy must have met around this time, but my main memory is of Robert telling me about an extraordinary Canadian lady called Margot Callas as we walked from Deya to Llucalcari. As we arrived at the beach there was a straw hat floating out at sea which slowly came closer and closer to the shore. The beach shelves very steeply there, so the straw hat floated into land, and suddenly stood upright, and from under it emerged the amazing face and figure of Margot Callas. I immediately understood why Robert was so entranced with another White Goddess. Margot and I became friends that summer and she was part of another group, another circle, who came to a farewell party at the Posada. Perhaps, one should never try to recapture past moments, because although the evening was pleasant enough, it has hardly remained in my memory, let alone anyone else's, as had the party above the Cala some years earlier.

In 1961, I was in Greece for the first time, and on arrival in Athens found out that Peggy Glanville-Hicks's opera was going to be performed. Peggy was an Australian composer whom I had met in 1956 when she was discussing with Robert the possibility of turning his novel Homer's Daughter into an opera to be called 'Nausicaa'. Peggy was extraordinary. I remember her once saying that "it doesn't matter where you live so long as you are never more than an hour away from a good international airport". At twenty-one this seemed like an improbable thought about a fantastical life. It turned out to be one of the most sensible pieces of advice I've ever been given.

'Nausicaa' was due to open at the Herodes Atticus Theatre two days after I was due to leave Greece. I reorganised my schedule, my travel arrangements and on returning to Athens found Peggy and Robert. Peggy said "take Robert off my hands so that I can concentrate on the final days of rehearsal", but Robert disappeared with Lucia who seemed entirely capable of looking after her father and entertaining him.

It was a wonderful opening night at that theatre immediately below the Parthenon and some old and some new friends were there. It was the first time that Robert and I met outside Mallorca. It was also the first time Robert had ever been to Greece!

1962

In 1962 Robert became Professor of Poetry at Oxford which meant that he had to give four lectures a year. Beryl rang and said could I find a flat for them which was big enough for occasional visits by the children, and needed to be in central London. They were prepared to pay up to E50 per week and I found them a suitable flat in Montagu Square. Robert and Beryl arrived in October. He was simply delighted with the public recognition his old university gave him with the prestigious appointment. Margot Callas, also arrived in London at the same time, had a flat elsewhere and started a course in photography. She came to a Thanksgiving dinner, which I gave in my flat in Sussex Gardens which Robert and Beryl didn't attend because they were in Oxford. I went to America for Christmas and when I returned Beryl said that Margot had disappeared. The next thing we all knew was she had become Mrs Mike Nichols.

1963

In that year I decided to radically change my life and go and live in America towards the end of the year. Before that there was another month in Deya which started with my having Margot's unused house in Llucalcari. I arrived with Kiki Botty, her boyfriend Julian Bevan and Ross Harvey. Outside the house there was Margot's

1930's Citroen, which I was told I could borrow for the time I was in Deya. Some of my guests found the house a little primitive but were enchanted by bathing at Llucalcari, and with Robert and Beryl coming to dinner on a couple of occasions. My friends became more enchanted when we moved for the final two weeks back to the Posada.

Lucia by this time was firmly attached to Ramon and we all went, one stifling hot evening, to Palma to the opening of his night club. Robert was there looking somewhat quizzical about an intended son-in-law being a drummer, and William was there thinking Ramon was exactly the sort of brother-in-law he would like. My father arrived for a little while. Another big party was given. There were some moonlight swims at the Cala and the occasional walk with Robert discussing Margot with increasing references to Cindy Laracuen. It was a summer of change, and I found myself counting days occasionally because I was both excited and apprehensive about the new course of life that I had chosen in the United States.

1964

New York was in place. I was working for Lever Brothers and was sharing a flat on the upper east side when I heard that Robert was going to be in New York with Cindy. This meant of course that I gave a lunch party for him and included my meeting a friend of Cindy's called Emily Reno Johnson, who became a good and close friend for the rest of my time in New York. Robert at that moment was much under Cindy' s spell and they were en- route for Mexico and I didn't see them again at that time.

1968

I had become a middle powered business executive with only two weeks' holiday, which meant climbing on and off aeroplanes furiously, and five days in Mallorca at Can Quet, a hotel which had been recently taken over by William and Elena. I arrived with an American friend and since I was such an old friend of the family, William decided that I could be put in any room and could be shifted frequently.

There was a set dinner, but guests were gently persuaded that the barbecue, which cost a little more, was the preferred method of dining. In retrospect the hotel had certain similarities to 'Fawlty Towers' but I had a wonderful time. Margot, now separated from Mike Nichols, appeared again and we decided to give a joint dinner party at a restaurant in the village for Robert and Beryl and eight other very close friends. Money was in our pockets, Margot was feeling extravagant, champagne flowed, and the only moment of tension was when Robert tried to stop Margot throwing full bottles of champagne randomly over the balcony of the restaurant on to the street below. Five days was hardly enough but I had to go on to Sardinia, or was it London?

1969

In March of 1969 1 shook the dust of America from my feet and returned to England on the SS France. I was due to start working for the family company, but offices had to be sorted out so I took three months island hopping in the Mediterranean. The first stop inevitably was Deya and Can Quet again with a great friend of mine from New York, a painter called John Day. I had enthused about Deya to him constantly and he may have been the only person who was underwhelmed by Deya, the ambience, and Robert and Beryl. But artists are notoriously egocentric, and somewhere amongst my souvenirs is a photo of John in the little restaurant at the beach at the Cala looking particularly disconsolate. I don't think I was, but I have also no recollection for once, of anything else that happened during that visit.

1973

My father and I had been on a business trip to Madrid, and decided to spend Easter in Deya with Julian and Mary Ashby staying at Es Moli. Of course we all turned up at Ca N' Alluny and Robert's initial reaction was one of disbelief that such good friends could possibly stay at such a blot on the landscape as Es Moli, and he proudly announced that he had never been there. Then, a look overcame him and he said that since we were there perhaps it would be all right for him to visit for dinner. This dinner duly took place, the manager of the hotel had been informed, the staff were on their best behaviour. Free champagne arrived and an extremely charming evening resulted. Was it helped by the fact that the barman was one of the fisherman's sons from the cottage I had had fifteen years ago?

On Easter Sunday, for the very first time, I went to Mass in the church at Deya and bought a I golden lithograph of the upper village which I gave to my father.

1974

In 1973 1 met an American called Gordon Taylor with whom I started to live. I had never lived with anyone before, and although Robert and Beryl must have known I was gay we never talked about any of my emotional involvements because they were so transitory. On January 1st of 1974, after a telephone call, Gordon and I arrived at Deya for five days to stay at La Torre, Robert's most private and special house. I felt very honoured that Robert had decided to lend it to us, and I remember going over the house on the first afternoon when he asked Gordon various testing questions about some of the objects. He pointed out a table and said what was so particular about it, and Gordon said it was made out of one piece of olive wood. Correct. Robert pointed out a piece of braided rope and Gordon said that it was an agale. Correct. But Gordon could not have known that it belonged to T .E. Lawrence.

Each morning Robert arrived at 8.00 0'clock with oranges, and on the first morning Gordon, with a raging hangover, said, on hearing the knock on the door, "who's there for Gods sake?" The answer from outside was "Beezelbub". I had never been in Deya in the winter and it was cold. There were charcoal braziers to heat us rather than the food. But it was wonderful to be with Robert and Beryl and with someone who was very important to me. We also met an 18-year-old girl called Julia Simone who was Robert's final White Goddess.

When we left Gordon understood a little more about the importance of Deya to me, but like certain visitors, was intimidated by the mountain of the Moon Goddess rising up and behind the village.

1975

We were invited to Robert's 80th birthday, but as we'd just started to run a little herb farm in Somerset I foolishly thought I was too busy to celebrate that occasion. My father was there I and I regret that I was not.

1985

Gordon and I and Louise Pleydell-Bouverie were on the island because we were looking for a house to buy or rent. We knew that Robert had been ill, but arrived one day to take Beryl and Paul Cooper

(Roger Cooper's brother) out to lunch at the restaurant at Can Quet (Can Quet had finally been swallowed up by Es Moli). Beryl told us a little about the last years in which Robert's mind had become entirely disorganised, and that she and other members of the family were awakened at any time of the night according to his whim.

After lunch she said she really didn't want anyone to see

Robert now, but as I was such an old friend she asked us back to Ca N' Alluny. Robert was lying on a chaise in the entrada, attended by a nurse and apparently asleep. He looked like some very old distinguished Roman emperor. He never knew that we were there, but I knew that it was unlikely that I would see him again, and I didn't.

But I will never forget the wonderful profile, at peace, silhouetted against the curtains of the window leading on to the balcony, where I had had so many conversations and so many drinks over so many years. Robert was the first great man I ever met, and maybe is the greatest man that I have known best. Knowing him gave me a confidence in myself and my abilities, which I had never suspected. As I go about the world and meet people, I think either of how Robert might behave in many different circumstances, or how he might expect me to behave. I gain enormous strength from this, and I am able to look at any situation and meet anybody with a confidence and directness that comes from my long and endearing friendship with the poet and writer called Robert Graves.

Robert wrote the following in an exercise book I kept from the fisherman's cottage in 1956. Marnie called me Yug, which is Guy backwards.

Guy has the cottage because he was once a kind and gallant Clifton school boy:

When a girl called Pamela (something) fell fowl of the fowl Oxford Jazz Club (back in 1952, I think, when Deya was a wilder place than now) he held her hand and dried her tears.

Anyhow: he really did something with that cottage, which was a sad place because of Juan Rasca's senile old mother with a lupus dying there: made it sing: filled it with flowers: put up a bookcase: threw splendid parties.

It is now renamed "Can Yug" in his honour.

Three cheers for Yug in three or four different languages!

Robert Graves (his mark) September 22nd 1956 & Beryl.

Jeremy Hogben' s Story - 1956

Dear Guy,

My apologies for taking such an age to respond to your letter and 'Memories of Robert', but we have been away on two occasions and I needed to settle down to get my thoughts in order. I'm afraid that my memories of Robert and Deya are very fragmentary -we were only there for a few weeks and only, regrettably, on one occasion, and that was over 40 years ago! Anyway, here goes: -

1956

Our first year at Cambridge when we created our (in)?famous double room overlooking Trumpington Street, and the opportunity to enjoy the freedom of the long vac. with a trip by car over land and sea to Mallorca. I had re-established contact with my old school friend from Rugby, Andrew Bonar Law, with whom I had been a fellow subaltern in the D.C.L.I. in the West Indies and we three set off in his heavy black Triumph Mayflower with very little money, camp beds, tarpaulins to sleep under and (to Andrew's amazement!), Guy's large metal trunk full of linen, silverware and other items more suited to our Corpus Salon than a fisherman's cottage! I forget details of the journey to the island but the impact of the dramatic approach road to Deya with the steep drop to the sea below are still with me. Andrew and I were full of expectation at the prospect of meeting the legendary Robert Graves and this was soon fulfilled when he and Beryl came down to see us after we had settled in to the cottage. The impression he made was of great kindness, inquisitiveness and complete lack of pomposity -very refreshing to us as young undergraduates recently subjected to arrogant school masters, senior officers and university authority. He was obviously delighted with the way the cottage had been domesticated (mainly from Guy's trunk) and he, I remember, told us never to put anything on the parapet of the well in the sitting room to avoid contamination of the only source of fresh water. Our days in Deya were spent swimming down off the rocks, approached by a very steep path, below the house, car trips to nearby places such as

Formentor, Puerto de Soller, Manacor etc., painting (I had brought my oils). The evenings were special with the enjoyment of the charcoal cooked dinners and discovery of Mediterranean foods and wine. The highlight was always the occasional visit from Robert who would call in perhaps after his regular trip down to bathe at the "naked and the dead' as I think he called it. We spent many evenings discussing a wide range of topics such as the Arab/Jewish conflict in Palestine (my father had recently written a paper on the subject and I was born there!), Andrew's family and political connections, writings of his father's Richard Law (Lord Coheraine) and Bonar-Law (PM. 1922) recollections. It was all a new experience to be in the company of such a distinguished person who treated you on an intellectual flat playing field. I think he was amused at our rather juvenile efforts to save money by concocting sun cream substitute "marinades' made of olive oil and lavender water (from the trunk?!) and driving down the steep road to Soller with the ignition switched off to save petrol! Andrew formed a passionate relationship with one of the maids from Robert and Beryl's household and would disappear off into the night for frequent trysts. I forget how long we were at Deya, but from some accounts I made in an exercise book in 1956, Andrew and I moved on by car, sleeping rough, through southern Spain, over to Tangier and then back to England. A memorable part of my life. My only regret is that I did not take enough notes (or photographs) of the unique opportunity to be with such a distinguished figure in the same way that I later (in the 1970's) enjoyed with Paddy and Vivienne Glenary (Campbell) in the south of France. Another story!

Julian Ashby' s Story - 1962

It was a part of my lucky year: after 27 years, I had found Mary and a job as a book publisher on the same day. We had just become engaged, and the hazy mists of new love surrounded our plans to holiday abroad on the scented isle of Mallorca. We planned to travel with Annie Snow, a friend from Cambridge days who always seemed to know more about life than anyone else I knew, and who had recently acquired a new admirer named Bruce, a brain specialist.

A week in paradise and Annie, through my flat-mate Guy, knew just the place that would suit this romantic intent: Deya. A village set high above a secret cove amongst olive groves where tourists were rarely seen, and where there was a small cafe with two rooms just large enough to house very small double beds, and views across the village church to the cliffs beyond with the sound of the sea and the smell of resin and charcoal and Mediterranean cooking.

There was a possibility that we might be invited to visit the legendary writer Robert Graves, whose brooding presence invested the village with a particular sanctity for someone who at that stage approached book publishing with a deal of literary idealism. I had read much of his prose work with great enthusiasm: I Claudius, Wife to Mr Milton and most recently The White Goddess, which had made a very deep impression on my imagination if not my understanding. I was also a passionate reader of poetry and had published a little of my own in a Cambridge magazine, but I had found Robert Graves' poetry very difficult. His poems seemed to worship women in a way I could not understand, though I placed them on a high pedestal too.

Our first visit to the Cala, running down through the ancient olive trees and coming upon fishing boats that seemed impossible to launch, a tiny eating place and the stony cove will never be forgotten. To our delight we found the Cala presided over by Beryl Graves, who was on her self-imposed tin-collecting patrol. She invited us to lunch the very next day. As we trekked back up the road an elegant black Citroen of pre-war origin drew up in a cloud of dust from which a mysterious tousle-haired, sallow, slim, dark-eyed woman emerged. We were introduced to Margot. She made a terrific impression: her magnetism, her restless unease, and her eyes. I saw her perhaps twice that week and yet fifteen years later recognised her instantly across a room in a friend's flat in New York. 'Ah, Deya!' she said. 'Yes, Deya...' and her voice trailed away.

We did go to lunch and the first impression of Robert was almost overwhelming, his physical presence, his superb head and ease of manner left me wordless. Fortunately Bruce's deep knowledge of the human brain fascinated Robert who was much enthused by mescaline and the mind bending drugs which were the talk of the time. There was general chat about the village and the cigarette smugglers who tore past our windows at night; one car turned over on the corner and the cigarette cartons were all over the place the next morning. Graves knew all about it and who did it. Their involvement with all things Mallorquine was fascinating. What was their position I wondered? Were they respected and loved yet regarded as foreigners, or were they truly accepted as part of the community? I heard William Graves 35 years later say that since that time the number of real villagers has dropped from 500 souls to 90, as they have sold out their houses to foreigners. But in those days foreigners were few and far between.

Mary and I walked on the mountain but did not dare to climb the rocky face above the village. We found an orchid of strange appearance and when we told Robert of it, he instantly identified it because it was growing through the beaten surface of the track. On out last visit to Ca N' Alluny, I dared to raise the subject of my enthusiasm for Robert's prose works, but I was rapidly cut short by the great man who dismissed all 'that' as catch-penny stuff unworthy of serious consideration.

We did not know it but the reason visits to London were in the air was that the Professorship of Poetry at Oxford must have been proposed. The year ended with a wonderful gathering organised by Guy in the rented flat in Montagu Square to celebrate Robert's election to the Chair.

1973

By now Mary and I were married with two babies and one salary. Guy's invitation to stay at Es Moli was delightful and affordable. But we were uneasy about staying there, and even the redoubtable Cooper pere could not predict Robert's reaction.

Luckily all was well, and we were swept along in the halo of the Cooper friendship with the Graves and were in and out of their house most days. Robert came down to the Cala with a new and voluptuous girl. She had trained as a dancer and two of her delicious physical characteristics were the deep dimples above her buttocks as she lay sun-bathing on the rocks. Robert and I invented a game of seeing who could most accurately land four pebbles (of jewel-like quality) in the dimples. I have a charming photograph of the winning throw.

Robert was in extraordinary physical health and challenged Mary to a swimming race round the outlying rocks. I remember running up to the top of the cliff anxiously to watch the progress and I feared certain drowning of the protagonists. Donald Cooper lay comfortably dozing on the rocks below, quite unperturbed by the goingson.

I was fascinated by the gliding, almost silent, presence of Robert's secretary in the background of our visits to Ca N' Alluny. I could hear him talk about foreign editions, mis-translations and all the details which a publisher knows so well. I wished to strike up a conversation with him but it would, it seemed, be out of place.

We made a wonderful expedition to Son Marrog and the Foradada and the cliffs beyond, watching the cormorants at their nests, before we said goodbye to Beryl and Robert.

It was 15 years before we visited Mallorca again, this time to stay with Guy in his lovely house in Pollensa. We drove over the mountain to lunch with Beryl and her striking daughter Lucia. That afternoon we walked up the little village street past the Posada, to the churchyard to pay our respects by the simple stone slab inscribed:

Robert Graves

Poeta

Guy and the Graves Family by Ross Harvey

I first met Guy at Christopher Fildes birthday party in 1955 drinking a great deal of Taylor's '04. I had never previously drunk such a splendid wine and it suffused proceedings in a numinous pink haze. The twelve of us were all 18-21 years old and if memory serves, our behaviour almost lived up to the very high standards of the hospitality. Our friendship therefore began auspiciously.

After my two years in the Royal Navy we resumed our friendship at Cambridge where Guy, two years my senior, had an established reputation for what in other circumstances would be called his salon where the company came from a wider social, intellectual and geographical spectrum than perhaps any other in the university. I then worked in Manchester for a few years and we resumed contact when I came to work in London in 1961. A New York lady of exotically mixed origins with a strong Hispanic content was very much part of Guy's intimate circle and it was with this lady's sister that we set out for my first visit to Majorca in 1963, reassured that dealing with the natives in a country district where English was unknown I would not be my problem ... or so I supposed — silly me.

So it was that one hot afternoon in June I first met the living legend Robert Graves and from the first moment he did not disappoint. The beguiling informality of the court of King Robert extended to going barefoot, something I had not done since my Canadian childhood and he mischievously, or so I think, encouraged me to discard my shoes and go for a swim which required one to walk the stony cliff path to the beach. Well, before I got there the soles of my feet were raw and bleeding but I had been initiated into a very privileged and interesting microcosm.

He and Beryl had lent Guy his guesthouse of which the address was No 32 and was therefore known to us as the trente dosshouse. The four of us made it our home for a fortnight during which time Guy was group leader. Then, as now, he seemed to think it normal to have a dinner or a lunch party almost every day and none of us were let off lightly. There was in those days only one dish in my repertoire and so I had to make it once or twice. First get your chicken. But there were no shops. There were, however, peasants who for a sum could be persuaded to strangle one at their door. Getting the strangling gesture understood was the easy bit but getting the sum sorted was what I imagined our partly Hispanic team member might contribute as words would have been a help. She revealed at this critical point that all her Spanish was in her blood, and as for the lingo she was pure Manhattan. This inconvenience she amply compensated for in the most obvious way by lavishing her attentions only on one of us and he was a slip of a lad who is now a leading criminal barrister while she is now the wife of a three star American Admiral. Such is the way of the world but it was not so clear when we were all twenty something and she still in her teens.

The Graves household was my first experience of a bohemian system that worked. I suspect that this was mostly because Beryl was as sensible and as capable as she looked while Robert seemed to feed his muse on an improbable court of extremely diverse types. Among those present during my short stay was a Persian prince from the Hindu Kush and apparently a direct descendant of the Prophet; also there was a woman of some mystery to me as she was of indeterminate nationality, with excellent Spanish, no shoes and a life style that involved much time in Mexico, New York and the Levant as well as Deya. She was intensely feline, being both aloof and warm and one could see that a man who pursues the 'goddess' should have such a character in his circle. Possibly products of the poppy fields paid for the airfares. Perhaps too the Persian prince really could illuminate some of the ancient myths as they mutate between cultures and over many centuries from the same rootstock — that was his role, as I understood it. There were many others flitting about this Bohemian court, but these two were to me the essence of its difference.

The base for all this activity was a large family ranging in age from under ten years to over sixty with Beryl at the centre of it. This gave it an air of solidity, despite the more obvious circus of which Guy and his guests became a part.

As well as the house we were given the use of a motor. It was an old 'traction-avant' Citroen with running boards and far too large for some of the tiny tracks that served as roads. With our typical grasp of Spanish we called it 'el gangster car' and one evening when driving back from Palma Guy thought I was going too fast and so turned the ignition off. This had the effect of locking the wheels in the 'straightahead' position, so if I was going too fast before I was now going too fast in a straight line, which might have been alright if the road was straight too. It was not, of course, and how we avoided a hell of a smash I'll never know.

It must have been that magic ingredient which seemed to pervade those weeks in Deya. Robert made time to be a teacher even to people less exotic than his principal courtiers. I was the privileged object of such an occasion when he showed me some of the books in his study and explained why he liked them. I will long remember it. That is true of the whole holiday which was so unlike life at home.

'That Give Delight and Hurt Not' by Francis Kinsman

Four of us had trundled through France to Barcelona in July 1956 and eventually arrived on a ferry at Palma, Majorca. We haggled ineffectually for a taxi, which took us at horrible speed along the coast road to Deya; suffering somewhat from vertigo, we were greeted by Guy, our host. We descended a steep hill through olive trees with our luggage to a blissful cottage overlooking the bay. It was a mystic place, silently over-shadowed by the brooding benevolence of Senor Robert Graves, the island's Prospero.

He was the High Priest of the community, and had designed matters to incorporate a bunch of six cottages close to his own large house, so that during the summer months he could ensconce for himself a small knot of like-minded people who might be amusing.

We didn't meet up with Robert for three or four days; he was writing and therefore not to be disturbed. But Guy was his friend and we were friends of Guy's and therefore ultimately welcome. He was, I understood from Beryl his wife, subject to creative tantrums and did not want to be encumbered by others at such moments. Understandable.

However, we eventually turned up for lunch and there was a coagulation of children milling about. About nine in fact, all with the same names and of the same ages; either of Robert's through Beryl, or grandchildren through the children of his previous wife. Heady stuff for an impressionable undergraduate like me. They all looked identical and it was complex to find out who belonged to whom. We had a vast and varied salad and paella you would kill for.

Our existence on Deya was as Guy describes. We talked into the night about exotic things and the various occupants of the other five cottages would come and spend time with us to discuss Abelard and Heloise; Machiavelli and Hitler; and argue a lot about the meaning of life and everything. The evenings and mornings were late. There were short, breathless expeditions through olive groves, over special walks of Guy's; sometimes we might find ourselves in

Valdemosa - it may have been where Chopin and Georges Sand had a fling but we felt that it was pretty noxious. There were possibly only 30 tourists there but we were disdainful of it; God knows what it must be like today. There were no tourists in Deya; just the confreres of the Magus -an irresistible Robert coterie.

We often foregathered on the beach for lunch, where the sardine boats would come in and we would eat the new-caught fish, fried, on our fingers and buy bread and fruit and wine from a tiny thatched shack, swim in easy waters and climb uphill again. It was wonderfully simple but subliminally complex at the same time. Robert was the Prospero of this island, full of sounds and sweet airs, a place seething not only with youthful intellectual fervour but also with novelty and romance. I recall an "action painter", who is now extremely famous and gets hundreds of thousands of pounds for his work, bringing down a newly painted canvas, covering it with methylated spirits, lighting it and pushing it out to sea. For me, aged 22, this was absolutely the life.

Because of the "sweet air" of romance, people tended to pair off like partridges in spring. My immediate group certainly did so, the four of them leaving me by myself. However, luck was in the driving seat because of the unbelievable Marnie Pomeroy, mentioned by Guy, an American silversmith whom either Robert or Beryl had the inspiration to sense that I would like to sit next to for lunch. I loved her immediately and totally. She was a year or two older than me which made her the more exotic and probably hopelessly out of my range.

But the scented isle did its work and she kept turning up.

There was this area of rocks termed by Robert "The Naked and the Dead", and she took to sitting there like the Copenhagen mermaid, in a bikini, combing her hair. She seemed to begin to do this as soon as I approached because I could see her not doing it as I crept down the olive-tree path towards the place. Captivated though I was, I did not think there was a chance that she would be in the slightest degree interested in me. However, on the third occasion that I went down and found her there with her long blond hair and her legs tucked under, I did venture to kiss her at which she trembled and said: "Francis, I'm not made of bricks". At the time, I did not know whether this was a put-off or a come-on -but being, at that age, an innocent, I took it to be a put-off. With hindsight, I fear I was wrong. However, I wrote her a poem, this being a poetic place par excellence, and she also being par excellence; on the major condition that it was not to be shown to Robert himself. Anyway, she liked it; it ran as follows:

The Mermaid of the silver shore Was singing as I watched her there;

How had I known it all before,

Each shivering note upon the air.

She sang me magically down,

Under the organ-welling tide

She crowned me with her coral crown I took her for my coral bride.

Sweet Mermaid of the silver shore, Why have you stolen me away?

Half lulled, half lost, I long for more Tomorrows such as yesterday.

We then swam together very closely and deliciously. Nobody else knew she was my Miranda and I her Ferdinand. The next day I went down again by myself to recapture this incident but a storm had blown up, lashing the Mediterranean about like nobody's business. I decided that in her honour I would swim round a little rock island in the middle of the bay, some distance.

I started out easily, but on my way back realised that things were not quite so brilliant. I was being dragged along the shore by the current, quite out of control. Though a poorish swimmer I just managed to struggle to a rocky cove in some distress. I never told anybody about this, either, particularly Marnie; it would have been too demeaning. But I felt I had accomplished myself for her and was delighted. It was a magic time -I shall never forget Robert's haunting presence; leonine, lordly and inspiring us to be and do the marvellous things we really were and wanted.

Finally, there was the great party and cabaret given by Guy for

Robert's guests and aficionados. I wrote an introductory song which

Guy has quoted. I also made him sing a piece of mine about the Piltdown Man, whose provenance was rather suspect at the time; which he performed in a brilliantly camp way.

We ended up with a treasure hunt in which one of the items was "a book by Robert Graves". There were four teams and we knew that there were only three of his books in the whole house. His was the last team to reach this stage, so no book. Whereupon he took a piece of paper, folded it in half to make four pages, and triumphantly wrote on the front " A Book by Robert Graves", on the inside "Da di da, dee di dee", and on the back " The End". Naturally, his team won the competition. I tried to persuade him to let me have the original with the thought that it would probably be worth thousands of pounds in the long run, but irritatingly he screwed it up and put it in his pocket.

So Marnie and I went outside and watched the stars.

Marnie, I remember you. Robert, so many thanks for that.