|

Search Help |

|

Links Robert Graves Website Other RG Resources |

Biographical Studies

Working with Robert Graves (with ilustrations)

Before I met Robert Graves I had collaborated with Brendan Behan and illustrated Brendan Behan's Island. It was the Book Society's choice for 1962 and a bestseller. Yet the book's appearance with illustrations by an English-man was greeted with resentment by some mostly Irish - critics. 'Your drawings', Brian Inglis (then editor of The Spectator) told me, 'would have been nothing without Brendan's text'. 'There wouldn't have been any text at all without my drawings!' I retorted.

After the frustrations of trying to get a text out of Behan which in the end had to be put on tape, it was a relief indeed to find that Robert Graves's text for Majorca Observed was, in fact, already written! Like Behan, Graves lived on an island. Even if his was adopted, I was to discover, it was no less loved. Desmond Flower, then literary director of Cassells, Graves's main London publishers, had long wanted him to write at length about Majorca and wondered if a series of evocative drawings of life and landscape might tempt the great man and bring such a book into being.

Our subsequent collaboration involved a memorable Odyssey which opened a completely new chapter of my life, besides inspiring me to create many of my finest drawings. Majorca Observed remains my favourite partnership with a writer although I don't think Graves took it all that seriously. But it turned out to be more than just a book. Robert and Beryl, and their four children (William, Lucia, Juan and Tomas), exuded an aura of such civilised charm that I eventually decided to live in Deya where they accepted me as a friend and a neighbour.

My wife, the Scots painter Pat Douthwaite, and our threeyear-old son Toby came with me. We established ourselves in a rambling old villa at Son Rapina on the outskirts of Palma which we nicknamed 'the villa of a hundred chairs'. I sent Desmond Flower's letter of introduction to Robert Graves, who immediately responded: 'What with house, children, garden, guests, work we never go visiting anywhere; but any time you care to come here, do. Afternoons are best, but not Tuesday or Fridays, when we are apt to shop in Palma.'

A few days later, I paused at the gate of Canellun, with my heart literally in my mouth. A tall figure wearing a large straw hat, baggy khaki shorts and rope sandals strode around a large and verdant garden. Suddenly, I lost my nerve. Without something worthy of his attention, I felt at a complete disadvantage. I could only face him with a portfolio bulging with superb drawings under my arm. And so, from April to August, 1963, I laboured to depict the island's life and landscape.

It was more than a labour of love. With hindsight, I recorded the last vestiges of the old traditional way of life that Graves felt so much at ease with. The Fifties had seen the advent of mass-tourism.

But tourists generally kept to the beaches and resorts that had sprung up around Palma. Elsewhere, narrow highways linked obscure towns and remote villages empty of buses and trucks. Cars were few: ancient Salmons, bull-nosed Citroens and Renaults of pre-1936 vintages and oddly enough the occasional Soviet-built Ford truck shipped to the Republicans during the Civil War. The main form of transport were two-wheeled traps and diligences drawn by mules or ponies.

The island possessed an architectural heritage which reflected Roman and Moorish influences. After depicting oil-pipeline construction across the Deep South, and where America's industry began in the Connecticut Valley for Fortune,2 1 revelled in drawing remote estates such as Al-fabia and Raixa with their tranquil pools fringed by tall palms and carpeted with water-lillies; seldom visited by Mallorcans let alone foreigners.

By the end of the summer, I had completed some forty large drawings in conté or ink on a handmade Saunders paper. I then took the bit between my teeth and wrote to Graves. 'I'll be glad,' he replied, 'to see what you have reaped.'3 This time I opened his gate and strode up to the house. All went well, with Graves (now Robert) relating anecdotes about the many artists he had known from his former father-in-law William Nicholson to Paul Nash and John Aldridge; most of whom, such as Eric Kennington (1888-1960) for example, were well thought of by me at the time. During the First World War, Robert had sat for him and helped the prickly Kennington to get accredited as an Official War Artist. Besides writing an eloquent introduction to his first one-man show 'The British Soldier' at the Leicester Galleries in June 19144 Graves had also persuaded T E Lawrence to appoint Kennington as art editor and draughtsman for the masterly Arab portraits in the Seven Pillars of Wisdom.

An empathy quickly developed between us. Even so, I was on tenterhooks as he began to look carefully through my drawings. But not only did he like them, especially those he described as 'the humorous ones' (I never understood what he meant by this), he started to think of his text, listing previously published essays and short stories (some had to be withdrawn as they were included in Collected Short

Stories).5 His only objection was the book being given the title of 'Robert Graves's Island'. 'After all,' he chortled, 'it isn't mine but theirs!' I replied that Doubleday, who were publishing the American edition, had thought up that title and suggested we call it Majorca Observed.

He then went on to tell me of his great love for Majorca and how he had walked over most of it. Pointing at various places on my map, he said I should not leave out this place or that village. For an island not more than fifty miles long, north to south and sixty east to west, there seemed a great variety of subject-matter. It became clear that I would need to return.

I did so in the spring of 1964. Robert wrote to confirm that

Karl Gay (his incomparable secretary-editor) had booked rooms at the Costa d'Or at Lluch Alcari, close to Canellun and Deya. 'The people there are good' Robert added, 'and the food better in April than in July by a long chalk' .6 The hotel itself was a fascinating survival from the Thirties with a clientele which resembled the cast of Jacques Tati's memorable farce, Monsieur Hulot's Holiday, who spent their days reading, correcting proofs or catching butterflies.

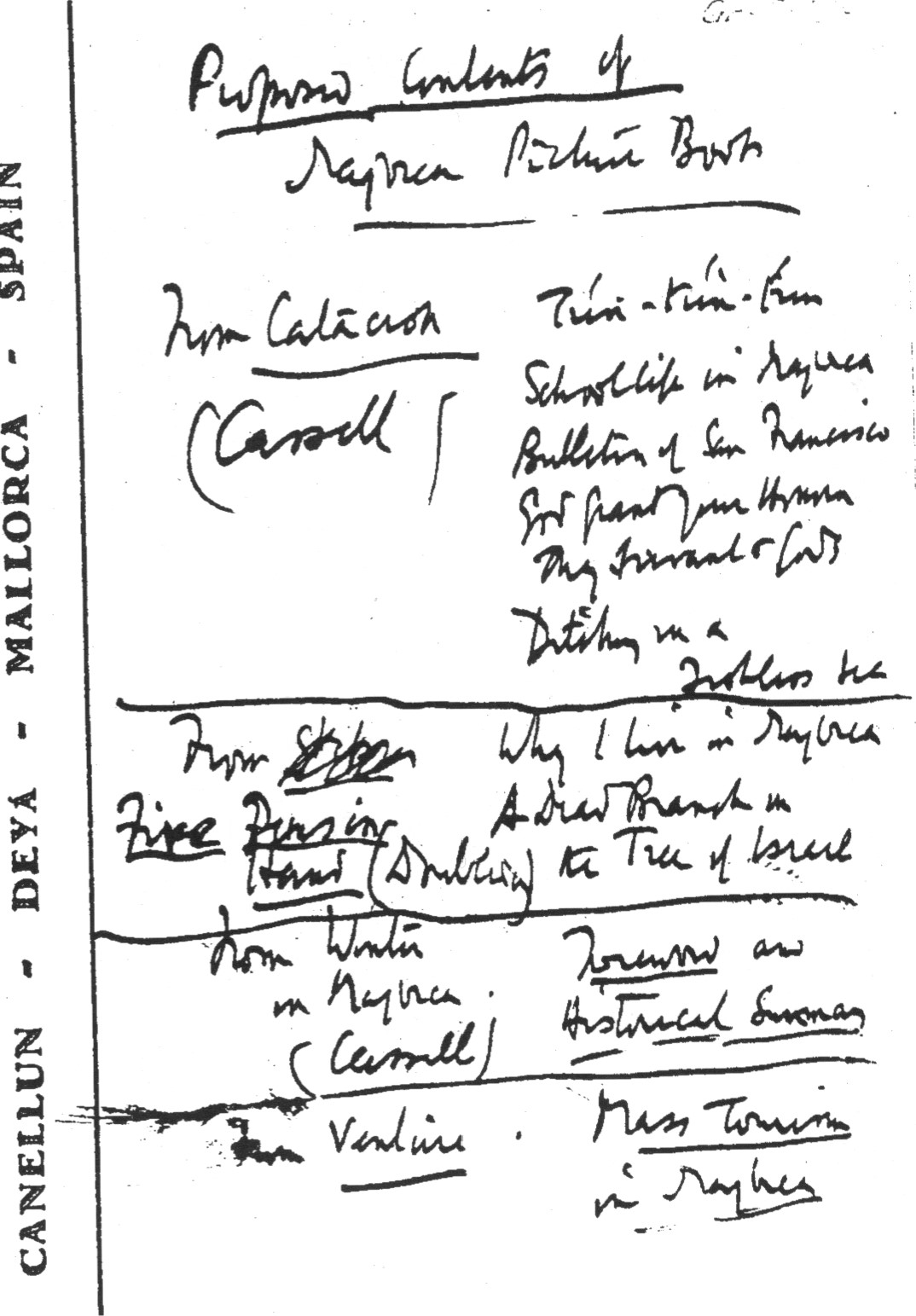

The next morning I walked to Canellun with Toby. We were greeted effusively by Robert as Karl ushered us into his workroom. Since our last meeting Robert had assembled the text for the 'Majorca Picture Book' as he now called it. He had dropped a heavy file on his right foot, which made walking painful. I was directed to open a great old chest and hand him a batch of typescripts which he later listed on a postcard (see illustration number 6). He then reviewed the subjects that remained to be drawn. These included Maria Bauza, a ninety-plus Deian and Don Ramon Compan of Lluch Alcari. 'I should not,' he added, 'leave out the hotel where D.H. Lawrence and Frieda stayed (from April to June 1929).7 Maria Bauza and Don Ramon were taken care of, but alas, I never got round to drawing where the Lawrences stayed until 1989 when I discovered the former Hotel Principe Alfonso in Terreno (which survives as the Canton Chinese Restaurant) and portrayed it in all its modernista glory.

Meanwhile, Toby had discovered Lucia Graves's old tricycle and was riding around the house with great glee, oblivious of a discussion about the possibility of Juan Graves working as my interpreter for the portraits of local dignitaries. 'Be quiet Toby!' barked Robert in his best parade-ground voice. 'Yes Rubber,' answered Toby. 'Rubber,' Robert repeated blankly. 'No one has ever called me RUBBER!' he roared, 'Call me Bob if you must!' 8

A delicious lunch followed, of garlicky ham and eggs, accompanied by a salad of tomatoes and pimientos, Benissalem wine with lemon-juice, and fruit, prepared by the gentle but sharp-witted Beryl. Robert kept up a monologue laced with scholarly asides. 'It is,' he admitted, 'a simple, but traditionally Mediterranean meal, Roman perhaps, although they would not have had the tomatoes.'

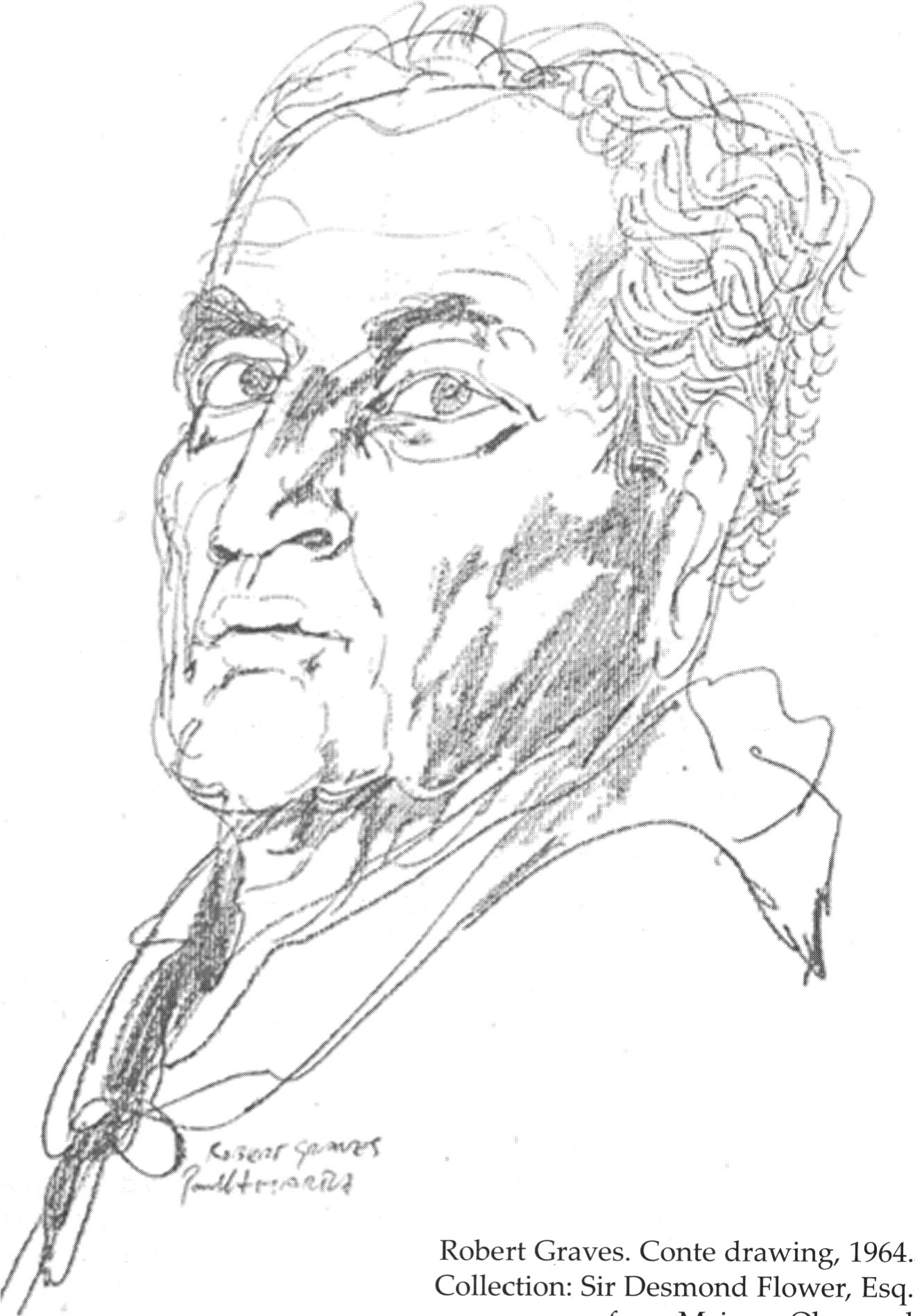

Desmond Flower was most anxious that I draw Robert's portrait. I dreaded having to do so. Although I had become an accomplished portraitist of not only the American workingman but of those European captains of industry who had been elected to the ranks of Fortune's top 500 capitalists. All had been especially anxious, therefore, to present a favourable image of themselves, which gave me the necessary licence to interpret their characters. Not surprisingly, few such portrait drawings, met with their approval. 'Surely, I thought, Robert Graves, would appreciate a candid characterisation of himself. Perversely, however, he did not!

He was, of course, what portrait painters call a 'natural'. At 68, his magnificently leonine head gave him the appearance of a Roman aristocrat. But le rejected the analogy. He clearly saw himself as a matinee idol! This was revealed by his unqualified approval of several appalling sketches made by his current muse, Cindy Laracuen Lee, who saw him as a Jean-Louis Barrault look-a-like in his younger days.

Moreover, he was in bad mood. Only that morning, a hawk had carried off the last of a cherished litter of Abyssinian kittens. But he did not want me to go away empty-handed. On the other hand, he would not respond to my requests that he try on his remarkable repertoire of stylish headgear. 'Draw me as I am or not at all! I he commanded. After breaking two graphite leads, I came up with a strongly expressive characterisation, only to be told he didn't like it! Yet, after Majorca Observed had been published, he told me that in fact, he liked it very much, indeed as had so many of his friends. I was talented, but I should always remember that people have a favourite age and prefer to be seen as thus.

'And what is yours?' I asked.

'Thirty-five' he snapped, with just a hint of a twinkle in his eyes.

Despite Robert's fear that the Church might censor Majorca

Observed in Spain, it turned out to be a modest bestseller on both sides of the Atlantic. 'I had no idea the book would get about so much' Robert wrote. 'The joke is, ' he added, 'that I haven't made a penny out of it -all my recent earnings and less recent earnings to the amount of EIO,OOO have been embezzled by my agent (International Authors NV) now in prison- and I can't get any new money through because only he can sign contracts, and in prison one can't swing a pen. Robert's advance and royalties, therefore, never reached him. His Switzerland-based agents had embezzled this substantial sum (E30,000 in today's money) along with an even larger amount from Graham Greene.

Towards the end of the Sixties, I finally succumbed to the heady ambience of Deya and the Camelot-like court of Robert and Beryl, and bought Ca'n Bi, a sixteenth century finca below the Puig. The old house in Es Clot had sheltered many painters, writers and musicians over the years. The celebrated Catalan painter Santiago Rusinol (1861-1931) was said to have stayed there, as had Manuel de Falla and the English illustrator Arthur Rackham (1867-1939).

Now that we lived in the village throughout the year, we became more closely acquainted with Robert and Beryl. Both were kind enough to put my mind at ease about buying the house as they had known its owner, Don Gerardo de Thomas Sabater since 1946.

Robert himself loved the old house and reminisced about the happy times spent there at Don Gerardo's musical soirées. Besides, its apple trees made the best jam in Deya. On one memorable occasion, Robert and Beryl joined us for dinner. Pat, had not been nicknamed the High Priestess of the Grotesque in British Art for nothing. Facing Robert that evening was one of her latest and most disturbing paintings; a huge gothic extravaganza which by accident or design, portrayed a witch-like female sucking the life-blood of a gaunt reclining figure which I was horrified to see, bore a striking resemblance to Robert himself! I was never able to discover if Pat's painting was a consciously made footnote on the Cindy affair, or an unconscious comment on the new relationship with Juli Simon. Robert shot Beryl a nervous glance and apologetically murmured that perhaps they might join us on another evening. I passed the bad news on to Pat, busily at work in the kitchen. 'They' bloody not going!' she hissed. Pat (who had danced with Margaret Morris's Celtic Ballet as a teenager) then appeared and began performing a writhing erotic dance. Robert was enchanted.

'Paul, I he grinned, 'we'll stay after all.'

Beryl too, came into sharper focus as it became apparent that we shared similar political opinions although my own faith in social ism had been severely dented by what I had seen on the streets of Warsaw in October 1956. Between 1968 and 1976 during periods away from Deya, we exchanged the occasional letter. She was especially interested in Russia since making her first visit there in 1965; and more so after hearing I had spent two months there early in 1967 with Alarj Jacob, making drawings for our Russian Journey. A year later, she planned a second visit, and to enliven her stay I gave her the telephone number of Edmund Stevens special correspondent of the

London Sunday Times and doyen of the foreign press corps in Moscow.

Early in May 1968, Beryl accompanied Robert on their first trip behind the Iron Curtain. He had been invited by PEN to give a series of readings in Budapest and initiate the Robert Graves Poetry Prize. To his delight he was feted and fussed over like a visiting monarch. They then went on to Moscow, a less successful visit as Robert found the city depressing as indeed it was at the time. Edmund Stevens, however, rose to the occasion and according to Beryl, 'invited people they wanted to meet' at his elegant eighteenth century mansion in the fashionable Arbat quarter. There, with his statuesque Russian wife, a former ballerina in the Imperial Ballet, Stevens entertained the political grandees of yesteryear who had survived the purges, the upand-coming, and licensed dissidents. Beryl and Robert were intrigued and curious to know how Stevens 'manages the best of both worlds'. 'Has he at some time done the Soviet gov[ernment] a service?' 12 continued Beryl. Indeed, he had, not only as a master of the licensed leak who gave the Western press what they wanted to believe, but as a KGB informant.

Although Beryl doesn't now remember who they met at the Stevens's soirée, and no record exists in Robert's diary, they did have tea with Nadezhda Mandelstam, the widow of the poet, Osip Mandelstam, then at work on her tragic memoirs, Hope Against Hope which were published in 1970. 13 This experience alone must have depressed Robert.

Beryl, as I did, loved Russia for itself; its incredible architecture; from the onion domes and the Moderne of Moscow to the

Palladian splendour of, Petersburg. On the merits of the Soviet regime itself, however, Beryl remained sceptical. 'I wonder,' she wrote, after her third visit with Tomas and Margot in 1969, 'if they've missed the road altogether and are going on being imperialists - pretending to be communists?' 14

I was always glad to return to Deya after the occasional working trip, usually to America but sometimes to Britain. Life and work could be resumed at a more leisurely pace. With Robert's encouragement Pat started work on a series of large pastel drawings with goddesses as her theme; one for each letter of the alphabet; each chosen by Robert. This extraordinary series was sponsored by the Scottish Arts

Council and shown at the Edinburgh festival of 1982 as Worshipped Women, to which Robert contributed an introduction. I began work on a portfolio of lithographs which incorporated handwritten poems by Robert, commissioned by the publisher Edward Booth-Clibborn and entitled, Deya.

One of the delights of living in Deya was the intense joie de vivre of the summer, the high point of which was, without any doubt, the summer play. The play itself had replaced Robert's birthday party on 24 July and that of William and Lucia previously on 22 July. By the early Sixties it had become a regular event when a little open-air theatre was built on the terrace of an olive grove below Canellun. There was never any plot, just a theme, sometimes written by its leading participants around an idea originated by Robert and produced by whoever had the time and energy, like the formidable Judy Stoma, a flinty Anglo-Irish ex-pat who had worked as a production assistant on various Hollywood epics filmed on location in mainland Spain.

One such play staged in 1967 reflected on a highly relevant topic - the smuggling of marihuana - loosely based on Aristophanes's satire, The Frogs; 'To the Lighthouse' was enlivened by comic choruses freely adapted from various Beatles songs. In a 8.5mm film I shot, Robert himself was a somewhat unconvincing Dionysus, whilst I played the part of 'Baron Von Krapp', the leader of the smugglers. Juli Simon gave bravura leaps in balletic interludes partnered by the everebullient Ralph Jacobs and two other girls whose names I have forgotten. George Simon also had a walk-on-part as an absent-minded lepidopterist complimented by the equally scatty Norman Jenkins, an American painter who played the itinerant artist unfolding his stool and setting up his easel to paint the inevitable pot-boiler. Much fun was had, both in rehearsals and the actual one-off performance when we forgot our lines and ad-libbed. The writer Jakov Lind, however, was not amused. It was his first summer in Deya and had just moved into the Mirador, a nearby summer pavilion to work on his novel, Soul of Wood, a Kafkaesque evocation of the Nazi occupation of his native Austria. Jakov darkly dismissed our play-making as being 'straight out of bloody Chekhov'. A hint perhaps of the catastrophe to come like that which engulfed Tsarist Russia.

Throughout 1971, I worked on the Deya lithographs, evolving five landscapes to accompany an equal number of poems, which were written by Robert on film so that they could be stripped on to the lithographic stones in the Paris studio of Mourlot. In an indirect or symbolic way, my images sought to express the poets' celebration of love, invoking moods of anticipation, rapture and ultimate betrayal. Robert made a short list of poems he had already written, and left me to decide which to interpret. He had given me eight, of which I chose five. I then tried to relate these to my own state of mind, and sought to find an equation. I suppose what I was trying to do was evoke, the euphoria of love. Robert's words were magical and gave me a renewed awareness not only of the contorted age-old olive groves, the parasol pines and the ruined towers set against a translucently turquoise sea but the very roots, stones and insects which lay beneath them. 15

Additional versions in watercolour were used as illustrations

for a third project, an editions-deluxe of selected verse entitled Poems. Introduced designed by Elaine Kerrigan, designed by Freeman Keith and printed by the Stinehour Press of Vermont, this handsome volume was published by the Limited Editions Club of New York in 1980. 16

It was during the final phase of the work on this book, that Robert's strong physique and questing spirit began to flag. He suffered increasingly from loss of memory and was unable to speak coherently as cerebral thrombosis gradually sapped his strength. By July 1980, he was unable to sign the colophon pages. He had gallantly managed a few, but as his signature became too illegible to decipher, the task was abandoned.

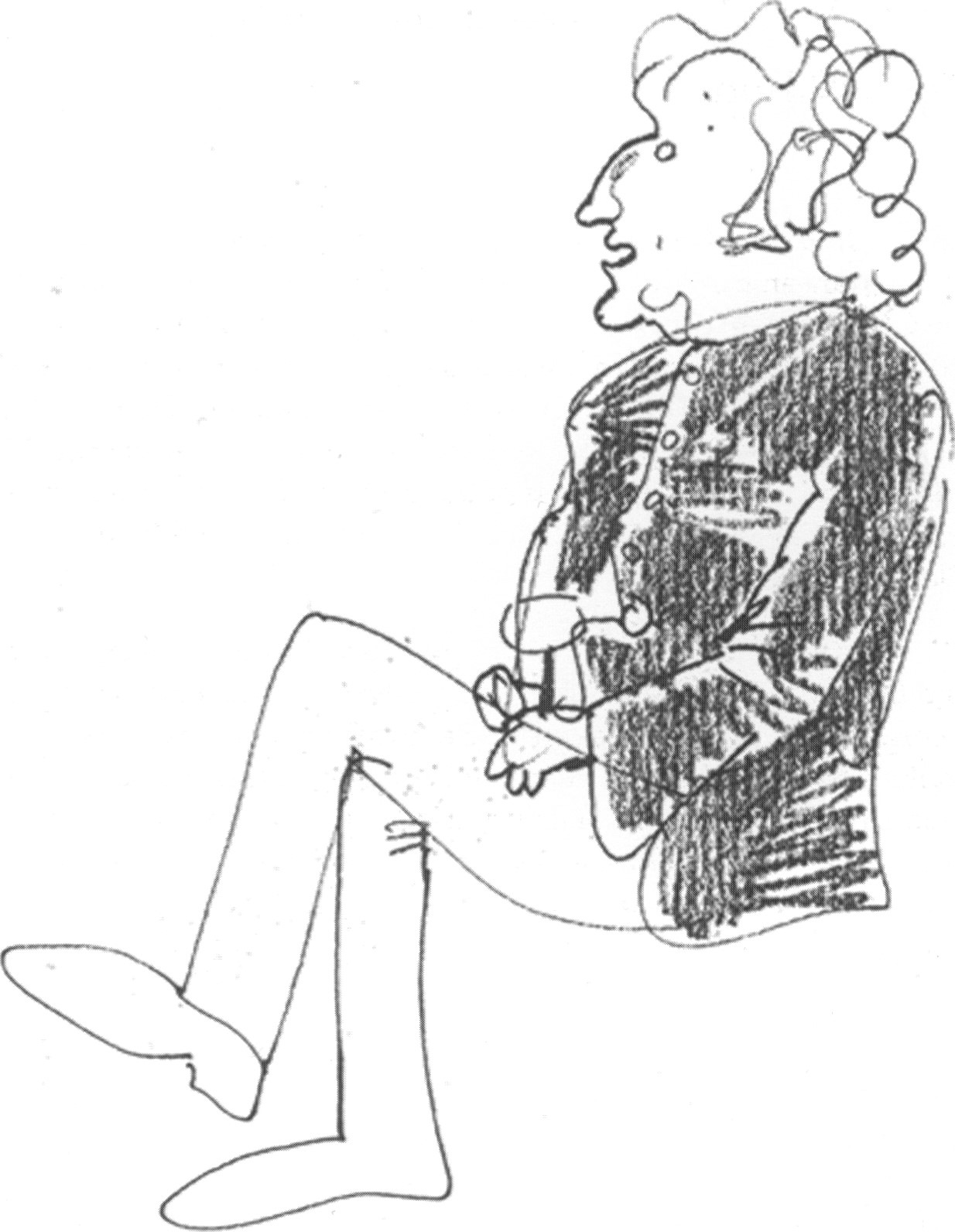

I last went to visit him a few days before his eighty-fourth birthday in July 1979. My companion was Eva Figes, who then spent part of her summers in Deya. Beryl made us welcome as Robert stumbled across the living room helped by Juan. Honor Wyatt was also present. As all began to talk, I took out a sketchbook and began to draw the noble grizzled head for what I felt had to be the last time. I visualised a medallion type of portrait in profile and sought to capture the now imperial cast of his features; for he had metamorphosed into a Roman emperor since I drew him in 1964. Suddenly, he sensed that I was not involved in the conversation around him and turned towards me.

'What' he gasped, 'are you doing?'

'Paul' interjected Beryl, 'is drawing your portrait for the book.' 17

'Well, ' Robert rejoined, 'let him get on with it!'

We all laughed. It was a flashback to Robert Graves in his prime.

Notes

L RG to PH, 30 March 1963.

2• Fortune 'Watching 2600 miles of Pipeline Growl Drawings by Paul Hogarth. February 1963.

'The Connecticut Valley, where American Industry began' Drawings by Paul Hogarth. December 1963.

3 • RG to PH, 17 August 1963.

4

. Harries, Meirion & Susie, The War Artists London: Michael Joseph,

1983.

5

•

6• RG to PH, 26 January 1964.

7• PH in conversation with RG

8• PH in conversation with RG

9• PH in conversation with RG

10• RG to PH, 8 January 1965

IL RG to PH, 12 October 1965

12

•

13

•

14• BG to PH, 12 February 1969

15• For detailed account with interviews with RG and PH, see 'Poetry and Art Combine' Robert Graves and Paul Hogarth collaborate' Daily Teleqraph Magazine 423, 8 December, 1972, 42-47

16• Poems was given the Francis Williams Award for the Best Literary Illustration between 1977-82

17. poems

Works Cited

Behan, Brendan. Brendan Behiln's Island. With drawings by Paul Hogarth.London: Hutchinson, 1962. Paperback edition, 1990 includes a preface by Paul Hogarth.

Graves, Robert & Hogarth, Paul. Maiorca Observed. London: Cassell, 1965. New York: Doubleday, 1965. Reprinted 1966.Reprinted 1997 by Ediciones La Foradada. (Jose de Olaneta, Palma de Mallorca).

Jacob, Alaric & Hogarth, Paul. A Russian Journey. London: Cassell, 1969. New York: Hill & Wang, 1969.

Graves, R P, Robert Graves & The White Goddess 1940-1985. London: Weidenfeld & Nicholson, 1995.

Letters from Robert Graves to Paul Hogarth, 1963-65. Courtesy, University of Victoria, British Columbia (Special Collections).

Letters from Beryl Graves to Paul Hogarth, 1968-69. In the possession of the author. Copyright Beryl Graves.

Graves, Robert & Hogarth, Paul. Deya. A Portfolio of Five Poems on lithographs. Edition of 75 signed and numbered by RG & PH. London: Motif Editions, 1972.

Douthwaite, Patricia. Worshipped Women. 26 drawings by Pat Douthwaite with an Introduction by Robert Graves. Edinburgh Festival, 1982.

Graves, Robert. Poems. Introduction by Elaine Kerrigan. Limited Editions Club of New York. New York, 1980.

Proposed contents of Majorca Picture Book (Majorca Observed). Undated postcard by Robert Graves. Ten items are listed, with indications of previous publication. In the published book, these were rearranged to make nine items. Courtest, University of Victoria, BC.

from from

from from

from

Majorca

Observed

from

Majorca

Observed

Paul Hogarth RA - Robert Graves watching the artist at work, Deya

1972.

Study of Robert Graves Standing.

Drawn at Canellun, 24 July 1975. Pencil.

30 x 24 cm. Courtesy, the Artist

Robert Graves at 80

Canellun, Deya, 1975.

Robert Graves at 84

Conte & Watercolour, 1979.

repro Newsletter of the Limited Editions Club of New York., 1980. Collection: The Artist

Robert Graves at Ca'n Susanna Deya, February 1967