|

Search Help |

|

Links Robert Graves Website Other RG Resources |

Critical Studies

The Telluric Factor in the Gestation of the White Goddess

In the centenary of the birth of Robert Graves I started to do some research into the almost lifelong relationship between the poet and Majorca—and more specifically with the mountain village of Deiä. I concluded that it most obviously constituted a very moving love story between an eccentric British writer and a Mediterranean island.

Perhaps, though, there was more to it than just that.

When celebrating the fiftieth anniversary of the publication of The White Goddess, I thought of looking more closely into the matter of whether Graves' working surroundings could be linked to his search for the language of true poetry through that myth.

• I. Deiä •

Robert Graves published his first chronicle of Deiä in 1948 after having lived there for about nine years. He had arrived there in 1929 and had been forced to absent himself from 1936 to 1946 due to the Spanish Civil War and, subsequently, the Second World War. That account appeared in The Saturday Book under the title of "The Place for a Holiday". Later on, heavily edited and enlarged, with a postscript added, and renamed "Why I Live in Majorca", it became the nucleus around which the book Majorca Observed, published in 1965, was woven.

In the first version of that piece, behind the bland title "The Place for a Holiday", we are surprised by forceful statements and strong feelings. Many inklings of the powerful attraction that Deiä exercised on Graves become apparent. The magic of the conjunction of the mountains, the woods, the sea, the wind, the moonlight... and the appalling heartsickness of being deprived of it all, are there:

of all Europe the place which arouses the keenest nostalgic sense (...) is Deiä in Majorca.

178

(...) One Colin Campbell had written in 1719: 'Deiå consists in Countrey Houses separated from one another. The many

Fountains, Groves and Fruit-trees that are here contribute extremely to the Pleasantness of the Place. The Church is in the middle of a Plain on the Top of a small Hill.'

A more lyrical note has been struck by travellers of the present century: (...) 'Deiå is a tiny hamlet perched on the apex of a hill overlooking a garden valley. (...) The quaint little houses with their roofs of ribbed tiles rise above each other in tiers or groups, but each with its little terraced garden, (...) The mountains are so near that they seem about to fall and crush the hamlet. Eagles swing above, and wild canaries dart and thrill below. (...) Foliage is everywhere reaching to the rose and white summits, and down to the hidden river. '

(...) These extracts are interesting mainly because they show the strange hallucinatory powers that Deiä exerts on visitors from Britain. Campbell saw the church and the country-houses but did not see the village; his successors see the village, but neither the church nor the country-houses. Campbell imagined a plain where there was only a steeply terraced valley with nowhere a broad enough level place for a

tennis-court; his successors hear the trilling of wild canaries —there are no wild canaries in the island— festoon barren precipices with foliage and crown them with eagle's eyries, and credit the houses of Deiä with non-existent gardens. Germans have written even more extravagantly about the place (...)

This hallucination may have something to do with the moon. The church is said to be built on the site of an Iberian shrine of the Moon-goddess, and I am prepared to swear that nowhere in Europe is moonlight so strong as in Deiä; one can even match colours by it. And moonlight is notorious for its derangement of the wits. (91-92)

That 'one Colin Campbell' invoked and quoted by Graves was the Reverend Colin Campbell, a learned army chaplain posted to the island of Minorca which was a British dominion for most of the 18th century. He was the author of the first known history of the Balearic Islands in English. The book, like many of the period that sported the word 'history' on the title page, was an eclectic concoction, a mixture of history, descriptive geography, customs, art, and natural history. Just as a sample of the pitch of some of the reverend's statements, he wrote that "The Countrey does not produce Wild-Beasts such as Lions, Wolves, Foxes and Boars; but it is infested with some other no less noxious creatures" (8) with no further explanation.

It is doubtful whether Campbell visited Deiä personally as he also described each and every town, village and hamlet of the Balearic Islands. He probably relied on second-hand accounts as many authors of the period used to do. For the historical part he translated the work of Joan Dameto and Vicenq Mut, two local 17th c. historians. The book was dated in 1715 and it was printed twice, in 1716 and in 1719.Graves had access to the second edition.

When I checked Graves' quotations on a first edition I realised that it was the very source from where he had acquired most of his knowledge about Majorcan history. Dameto and Mut, in spite of being the fathers of Majorcan historical studies, produced a work full of topics, errors and inaccuracies which have been challenged and corrected by subsequent generations of historians. Many of those wrong notions slipped into the writings of Graves who, on the other hand, showed a sharp insight when he dealt with contemporary Majorcan affairs. One example is his idea of the nature of the language spoken in the island; a matter to which I will refer later.

Nevertheless, going back to "The Place for a Holiday", the idea of the tellurian strength of Deiä is clearly expressed. By the way, the absence of tennis-courts in Deiä was not a matter of room, but of money; Richard Branson has had some built at the bottom of a deep ravine for the benefit of the customers of his Deiå hotel.

The magic of Deiä was not lost on the biographer Miranda Seymour when describing the first feelings that assaulted the poet when he arrived there: "Watching the sun dye the soaring walls of the Teix mountain crimson before they blanched in the ashy glitter of the moon, Graves had a sense of being in the landscape to which he belonged. In its bleakness and simplicity, the combination of mountains, sea and grey rock, Deiä took him back to Harlech. There was no ruined castle there, but this, too, was a landscape made for legends.

(...) One Colin Campbell had written in 1719: 'Deiå consists in Countrey Houses separated from one another. The many

Fountains, Groves and Fruit-trees that are here contribute extremely to the Pleasantness of the Place. The Church is in the middle of a Plain on the Top of a small Hill.'

A more lyrical note has been struck by travellers of the present century: (...) 'Deiå is a tiny hamlet perched on the apex of a hill overlooking a garden valley. (...) The quaint little houses with their roofs of ribbed tiles rise above each other in tiers or groups, but each with its little terraced garden, (...) The mountains are so near that they seem about to fall and crush the hamlet. Eagles swing above, and wild canaries dart and thrill below. (...) Foliage is everywhere reaching to the rose and white summits, and down to the hidden river. '

(...) These extracts are interesting mainly because they show the strange hallucinatory powers that Deiä exerts on visitors from Britain. Campbell saw the church and the country-houses but did not see the village; his successors see the village, but neither the church nor the country-houses. Campbell imagined a plain where there was only a steeply terraced valley with nowhere a broad enough level place for a tennis-court; his successors hear the trilling of wild canaries —there are no wild canaries in the island— festoon barren precipices with foliage and crown them with eagle's eyries, and credit the houses of Deiä with non-existent gardens. Germans have written even more extravagantly about the place (...)

This hallucination may have something to do with the moon. The church is said to be built on the site of an Iberian shrine of the Moon-goddess, and I am prepared to swear that nowhere in Europe is moonlight so strong as in Deiä; one can even match colours by it. And moonlight is notorious for its derangement of the wits. (91-92)

That 'one Colin Campbell' invoked and quoted by Graves was the Reverend Colin Campbell, a learned army chaplain posted to the island of Minorca which was a British dominion for most of the 18th century. He was the author of the first known history of the Balearic Islands in English. The book, like many of the period that sported the word 'history' on the title page, was an eclectic concoction, a mixture of history, descriptive geography, customs, art, and natural history. Just as a sample of the pitch of some of the reverend's statements, he wrote that "The Countrey does not produce Wild-Beasts such as Lions, Wolves, Foxes and Boars; but it is infested with some other no less noxious creatures" (8) with no further explanation.

It is doubtful whether Campbell visited Deiä personally as he also described each and every town, village and hamlet of the Balearic Islands. He probably relied on second-hand accounts as many authors of the period used to do. For the historical part he translated the work of Joan Dameto and Vicenq Mut, two local 17th c. historians. The book was dated in 1715 and it was printed twice, in 1716 and in 1719.

Graves had access to the second edition.

When I checked Graves' quotations on a first edition I realised that it was the very source from where he had acquired most of his knowledge about Majorcan history. Dameto and Mut, in spite of being the fathers of Majorcan historical studies, produced a work full of topics, errors and inaccuracies which have been challenged and corrected by subsequent generations of historians. Many of those wrong notions slipped into the writings of Graves who, on the other hand, showed a sharp insight when he dealt with contemporary Majorcan affairs. One example is his idea of the nature of the language spoken in the island; a matter to which I will refer later.

Nevertheless, going back to "The Place for a Holiday", the idea of the tellurian strength of Deiä is clearly expressed. By the way, the absence of tennis-courts in Deiä was not a matter of room, but of money; Richard Branson has had some built at the bottom of a deep ravine for the benefit of the customers of his Deiä hotel.

The magic of Deiä was not lost on the biographer Miranda Seymour when describing the first feelings that assaulted the poet when he arrived there: "Watching the sun dye the soaring walls of the Teix mountain crimson before they blanched in the ashy glitter of the moon, Graves had a sense of being in the landscape to which he belonged. In its bleakness and simplicity, the combination of mountains, sea and grey rock, Deiä took him back to Harlech. There was no ruined castle there, but this, too, was a landscape made for legends.

Deiä corresponds to the Greek hea, meaning, goddess. It seemed entirely credible that this place, where the moon shone brightly enough on the Teix's walls to make day of night, should have been chosen for a primitive place of worship. To superstitious souls like Graves and Riding, it was a setting of magnetic power." (190-191)

11. The Moon •

Some relevant words are present in the preceding quotation: moon, goddess, magnetism. As we have already seen, Graves was obsessed by the moonlight of Deiä and he put it in writing on many occasions. During his first stay in the island, Graves had been very fond of inventing games to amuse his and Laura Riding's circle of friends. One of those games was played late at night, when Robert's party returned home along the unlit Deiä road after an evening spent at the village café. It consisted on identifying, by moonlight only, the colours of every garment they wore; even the different colours of the most complicated pattern printed on a neckerchief or shawl.

In 1931 Graves embarked on his well known adventure as a developer, trying to buy all the land between his home and the sea so as to avoid the building of an imaginary hotel run by Germans next to his home. He was convinced of this need by Laura and Gelat, his Majorcan friend and business partner, who took advantage of his proverbial dislike of the aforementioned nationals. That domain, designed to become the seat of a university to teach Laura's apocalyptic view of life was to be called Luna Land.

The poet also insisted on the deranging powers of the moonlight.

In June 1932, a surprising piece of news appeared on the front page of The Daily Palma Post alongside the information that a gang war had started in Chicago following the assassination of Al Capone's personal secretary. It was headed "Graves Would Become Deiä Dictator" and reported that:

in the Deiä hotel in which Robert Graves, athletic English author, threatened to become dictator of the colony.

Germans in their cups began to chide the Englishman for being a renegade German, since they pointed out that Graves is descended from Germans.

The attack was so bitter that Graves was impelled to strike out. His first blow was a clean knockout, but all the Germans immediately set upon him. By good manoeuvring he escaped, and collecting an Anglo-American following descended on the café to clean it out.

Four days later an angry letter by Graves forced an apology from the editors. The letter explained that

over a year ago (...) one evening in the presence of a number of village people I protested against the loose and vindictive manner in which a foreigner had been speaking about another foreigner, a friend of mine, of a different nationality from either of us who was at the time not physically able to act personally. I explained, with apologies, that as the representative of my slandered friend I was about to slap the slanderer's face. I then did so.

The only sequel to this was an accidental one. A foreigner of still another nationality and a friend neither of my friend, the person I slapped, nor myself, assaulted me one night on the road under the pretext of partisan feeling on the matter (...) I was obliged to knock him down.

The incident is partially clarified in Richard Perceval Graves' biography through a letter by Graves to John Aldridge. (160-161) It seems that the slandered friend was Laura Riding and the bellicose attacker was a Swede who, having already had argued with Graves, stood one night shouting before the poet's house waking everybody up. Graves went down, fought with him and went back to bed. That seems to be the most sensible and certified account; but I still like to imagine what Graves hinted in his letter to the newspaper, two deranged men throwing their fists against each other on a deserted, dusty road under the moon.

The Daily Palma Post, by the way, is an early sample of the long tradition of English daily papers in Majorca. Nowadays, the Majorca Daily Bulletin, now well into its thirty-six year of life, is the only English paper that is entirely written, edited and printed in Spain. These days, one has to look for it at the newstands behind or under the Mallorca Magazin, the German weekly. It has been reported that the Germans already own the 20% of the island; it seems that Graves' ancestral fear of a German invasion had a certain prophetic quality.

According to Cristöfol Serra, a Majorcan intellectual and poet and an expert in obscure symbols, there are two places in Majorca very much influenced by the moon. Deiä and Port d'Andratx, some twenty miles to the south-west along the coast, where the German top model Claudia Schiffer and her fellow countryman, the Formula One driver, Michael Schumacher have built their villas and where the crabs are affected by a restless madness every full moon.

Graves was also well aware that it is believed that at the top of the Deiä hill there was an Iberian shrine dedicated to the worship of the Moon-goddess. In 1934 a house in this very site, next to the church, called Sa Posada, came up for sale. Graves acquired it and the diary he started to keep the following year is full of enthusiastic references to the house. Curiously enough, it was the only one of his properties that he always kept in his own name; perhaps he could not bear the idea of parting with a place with such strong connections with the figure of the White Goddess. It is true that in his old age, after having bequeathed the house to his son William, he donated it verbally to his penultimate muse Cindy Lee. A problem which was solved with a brief bout of family unpleasantness. The name of the house, Sa

Posada, has often been translated as 'the inn.' That is not very accurate as those kind of houses are common in rural Majorca and they have got nothing to do with a public inn. They used to belong to owners of substantial estates in the country—in this case it was part of the Es Moli estate—and they were used for spending the night in the village or town when the estate owners went there for business or pleasure. Perhaps the word 'pied-ä-terre' would convey the meaning more precisely.

In rural Majorca again, the influence of the moon has always been highly regarded. The calendar of the peasants was based on the cycles of the moon, not on the phases of the sun; and it was consequently called llunari pages, the peasant's moon-calendar. So strong is the tradition that in 1995, on the occasion of the centenary of Robert Graves, a Palma art school and a secondary school embarked in the design of a 1996 moon-calendar directed by the teacher and artist Maria Lluisa Agui16, a dear friend of mine. The result was a beautifully printed job, depicting a powerful photograph of the poet in its front page and containing thirteen months for the thirteen lunar cycles, each one headed with the corresponding Gaelic magical tree, animal and colour next to their Majorcan counterparts.

As we have already seen, Graves stated repeatedly that the moonlight of Deiä had a unique strength. When I contacted the Physics Department of our University with the intention of looking seriously into the matter I was received with polite, sceptical smiles. I tried to interest them in some practical research, like measuring the intensity of the moonlight in Deiä under a full moon, my powers of persuasion failed; not even dropping the name of my main witness, Robert Graves himself, seemed to carry any weight.

I was kindly explained that the distance from the earth to the moon is so great that one's location on the planet does not make any difference in the perception of the strength of the light reflected by the satellite. In the best of cases, a very pure atmosphere would help to ensure the optimum transmission of light. Also, the shorter the distance to the Equator, the higher the place of the moon in the sky vault. This means that the light would cross the atmosphere by a shorter, more perpendicular route, thus ensuring a smaller loss of intensity. So, a low latitude would also help.

In this sense Deiä, with a latitude of 39.7 degrees North, is not badly placed. Moreover, the orography of the terrain may also be influential to the point as the village is encased in an amphitheatre of limestone mountain walls of a whitish grey that might reflect and enhance the moonlight.

But in the end the physicists refused to endorse the notion that there is any special relationship between Deiä and the moon. When I pointed out the fact that Graves was a poet, not a physicist, they did not seem impressed at all.

• 111. The Wind •

The winds are another force of nature which are linked to the White Goddess myth in Robert Graves book

Whistling three times in honour of the White Goddess is the traditional witch way of raising the wind (...) (433)

In Majorca you can still find at the potter's stalls of any country fair the siurells, some white clay figurines decorated in red and green with a whistle attached to them. They are displayed alongside terracotta pots and pans the shapes of which remember those of the Phoenician and Roman specimens to be found at the museums. To most people the siurells are just a whistle, meant as a toy for children, from an age when plastic did not exist. Probably they have been saved from extinction because they have the right size, weight, price and charm to become a nice souvenir.

Their subjects are always the same, a man with a hat and a long staff, a horseman, the devil, and a lady, a matronly figure. Some anthropologists have seen them as magical totems used to call the necessary winds for the winnowing, a theory enthusiastically embraced by Robert Graves. He described them at length in The White Goddess and identified each of the characters with a Greek deity. The potters who make them usually respect scrupulously the traditional forms but, being a popular art, they cannot avoid looking for inspiration around them. I can swear I have seen Dionysus on a Harley-Davidson motorcycle and Aphrodite on a wind-surf board.

In November 1995, a wonderful exhibition on Robert Graves life was opened in Palma. A painting by Nils Burwitz was hung in a prominent position and it was used on the cover of the catalogue. In it, the White Goddess was represented as a siurell, green and red on white, the half-moon horns on her head, the serpent in her right hand and the double-edged axe in her left hand.

Strong winds in Deiä can have an unsettling effect, they can even carry some danger. The half circle of mountains that hug the village has sometimes turned a strong gust of wind into a cap de fiblö, a sort of Mediterranean tornado smaller and more short-lived than the tropical kind but capable of putting lives in danger and causing appalling damage. It is a rare phenomenon but by no means unknown in the life span of a Deiå native.

The writer Anais Nin remarked on the wind of Deiä. She visited the village as most writers who set foot on the island did. There was a time when any hotel manager asked by a customer to recommend a nice place to rent a house for a period and settle down to write, would invariably point to Deiä. The fame and prestige of Graves had given the village the halo of 'the writer's place.' Anais Nin picked some days in which the south-east was blowing, a hot and asphyxiating wind which carries the dust of the North African desert and causes powdery whirlwinds that have the most unsettling effect on people. It inspired her a vivid short story appropriately titled Sirocco that appeared in her collection Little Birds.

• IV. The Magnetic Mountain •

Graves never tired of repeating to whomever wanted to listen, that the Teix mountain that looms over Deiä held a strong magnetic power. Its effects on a creative mind were positive, enhancing the creativity, but on an idle mind they could end in madness, a very negative form of madness. He even went as far as presenting his friends and visitors with stones from the Teix so as they could carry with them some of the mountain magnetism.

Anthony Burgess wrote in his autobiography that: "Deiä had little to recommend it except the Graves magic. A literal magic, apparently, since the hills were said to be full of iron of a highly magnetic type, which drew at the metal deposits of the brain and made people mad. Graves himself was said to go around sputtering exorcisms while waving an olive branch." (199) This time I knew better than to approach the Department of Geology. Even I knew that the Teix is a block of limestone in which the metallic components are negligible if existent. About the metal deposits of the brain I am still an ignoramus. Instead, I turned to the writings of Carlos Garrido, who has been doing the most comprehensive research and compilation of the magical aspects of the Balearic Islands. I was thrilled when I discovered that a whole section of his book Mallorca mågica dealt with the magic mountains and one chapter was on the Teix. My excitement turned into discomfiture when I read that the main proof of the supernatural power of the mountain was... the influence it had exercised on Robert Graves!. Apart from that, there are some recorded UFO sightings, 'King James' chair' —a throne sculpted in the rock from where one of the three Jameses of the Royal House of Majorca liked to watch his dominion—and some old legends. In times past, peasants from the plain went to the Teix for some seasonal forestry tasks, when they came back they told strange stories, possibly seeking the admiration of their fellow villagers. This was the origin of those legends.

Nevertheless, I am acquainted with some members of an informal, friendly club of hill walkers that go to the Teix every full moon and, no matter the weather, sleep in the open air. They must find something in it, as they keep on going up there.

But that positive magnetism that Graves, there is no doubt, sincerely felt in Deiä, can also be seen from the reverse side: the intense homesickness he suffered when away. Miranda Seymour again reported it very perceptively when describing the arrival of Laura Riding and Graves in London after they had had to flee because of the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War: "Mary [Sommervillel took Graves and Riding out to supper at the Café Royal on their first evening in London. Her guests were unable to make more than a polite pretence of enjoying themselves. They had gone for less than a week and the sense of homesickness was already overwhelming. (...) [Robert], deprived of his daily routine and his familiar landscape, (...) was restless and lost. Karl, who had enjoyed listening to the ballads he sang while he worked in the Canellufi kitchen, noticed that he sang no more after their arrival in England. It is striking too, that he suffered continuous poor health for the next two years. (...) Laura, often working until near dawn on her book about Troy, wrote with uncharacteristic pathos about Cressida's sense of being exiled from Tenedos, her island home." (241-243)

• V. A Society Ruled by Goddesses •

The Majorcan rural society has marked matriarchal features as many anthropologists have pointed out. In the country it is quite common for the mother of the family to hold absolute authority and to make all important decisions. The Majorcan word madona is a very clear example of that. It is originally the same word as the Italian madonna, but having developed a very different meaning. Madona has, in fact, two meanings depending on the context. It means 'the lady of the house', but also 'female owner' in general, from the largest property to the most trivial object.

In the past, before the improvement of communications, Majorcan villages were sealed societies where endogamy was unavoidable. Surnames kept repeating themselves and, as an old Majorcan custom is to give the children the Christian names of their grandparents, there is also a surprisingly poor variety of those. This created a serious problem of identification, hence the important role of nicknames. They were used as surnames and were passed from parents to children. They were also eventually renewed when an individual did a remarkable feat or, very often, for the most trifling reason which was forgotten in two generations.

As often as not, the sons and daughters turned out to be called by their mother's nickname, not their father's who, presently, ended answering to his wife's nickname. That matriarchal feature is most striking when we realise that a nickname had the full value of a surname, if not more.

Also, the old Majorcan marriage law, still in force, allows the wife to buy, keep, and dispose of property with complete independence of her husband, an independence extended to all her properties acquired previous to marriage. All marriages that take place in the island are automatically bound by that law which strongly differs from the one that rules in the rest of the Spanish State which is much less respectful to the right to property of married women.

The kind of couple that Robert Graves and Laura Riding were helped them to blend surprisingly well into Majorcan society. Seymour's biography showed an amazing coincidence between Graves' opinions and Majorcan law and custom when Robert properties were nominally transferred to Laura: "He had long been convinced that women had a better right to be property owners than their menfolk. (...) As the owner, a woman achieved independence and a measure of esteem; (...) this gift was no less than Graves was ready to offer any of the muses of his later years. It was one of the ways in which he choose to honour the women he venerated." (207)

It has often been said that the people of Deiä thought at first that Robert was Laura's servant given his devotion for her and the contrast in their appearance. She wore rich antique Majorcan garments, which did not look ridiculous on her, and he dressed with his usual simplicity and carelessness. I do not quite agree with this. In spite of being unable to prove it, I suspect that to the eyes of many local people they were just another couple with a conspicuous madona, a kind of couple of which you could find thousands of examples in Majorcan villages. Obviously, Laura was many steps above a simple madona, she was a queen, a goddess. The same biographer expressed it brilliantly: "As a poet, he was ready unequivocally to declare himself the servant of his personal muse. The poems which appeared as Ten Poems More in June 1930 were written during the first winter months (...) In one of this collection, 'The Terraced Valley', Riding was presented as the mythical queen of Deiä. (...) Epilogue I, published in (...) 1935, contained poems which (...) mythologized Riding's authoritative role, (...) the images are chilling (...) she is the moon (...) she is Fate (...) she is compared to the cold brilliance of crystals." (193, 234-235)

There is little doubt that The White Goddess was conceived in such an atmosphere, so laden with magical, magnetic, mythical and feminine currents. In the autumn of 1933, Laura Riding, with the help of Eirlys Roberts, was working on a book about the role of women. The idea had sprung from Laura's conversations with Graves about the essence of myth. The results were published much later, in 1993, under the title The Word 'Woman' and Other Related Writings. The book has sometimes been seen as a precursor of The White Goddess.

Notwithstanding Graves' empathy with the genius of rural Majorca, his knowledge of Majorcan things was haphazard and chaotic, in spite of being highly intuitive and regularly correct. The kind of language spoken in the island was one of the things he was never able to get a clear idea of, and, what is more, he never bothered to fill that gap. The misnaming of his home, Canellufi, has been a matter abundantly commented on. In the name even there is a character that does not belong to the Catalan alphabet, the Spanish ene

Graves wrote a great deal of nonsense about Majorcan language, calling it purer than Catalan and Provencal, a sort of Italianish French or a coarse dialect of Spanish; words that have caused much astonishment and indignation when read by Catalan philologists. Some of those absurd notions had been learnt in Campbell's translation of Dameto and Mut, the two 17th c. local historians who were by no means specialised in the study of languages. Graves did not take the trouble to revise or to update those mistaken assumptions.

Native Majorcans speak Catalan, a language spoken in French Catalonia, a region north-east of the Pyrenees; in the Spanish east coast, as far south as Alacant (Alicante), a strip several hundred miles deep in most places; in the Balearic Islands and in the town of Alguer (Alghero) in Sardinia—a living remainder of the ancient Catalan Mediterranean empire that stretched as far as Istanbul. The speech of a

Majorcan and that of a French Catalan differ much less than that of a Yorkshireman and a Highlander. It is a community of six million speakers, as many as that of all the Scandinavian languages put together.

At the end of the seventies, after the death of Franco, nationalism resurfaced in force and language became a political issue. Some representatives of a nationalist political party tried to enrol Graves in a campaign to reinstate Catalan as the official language. Graves absolutely refused. The story was not made public and I learnt about it only very recently through a friend of mine who is an old member of that party.

I had to explain to him Graves' principle of not interfering in local affairs as it is expected from a well-mannered guest and that he could probably sense that there were some very strong feelings behind the matter. Moreover, he probably was surprised to learn that Catalan was spoken on the island. My friend told me that the nationalists who were privy to the story did not have a high regard for Graves. I pointed out to him that they probably had not read his excellent novels, his wonderful poetry or his amazing classical studies either.

Nevertheless, I am sure that the Majorcans who have, would love the image of a White Goddess, followed by a twice-born

Dyonisus a few steps behind, disembarking in an old, magical island where the inhabitants wore no clothes. The men carried three slings; one in their hands, for stones; the second, smaller, tied around their foreheads, for pellets, as deadly as lightning; and the third, the largest, around their waists, for rocks that could stop a Roman horse.

Works Cited

Burgess, Anthony. You've Had Your Time. The Second Part of the Confessions.

London: Heinemann, 1990.

Campbell, Colin. Ancient and Modern History of the Balearick Islands, The.

London: William Innys, 1716.

Garrido, Carlos. Mallorca mägica. Palma: Olafieta, 1987.

Graves, Richard Perceval. Robert Graves. The Years With Laura 1926-1940.

London: Weidenfeld, 1990.

Graves, Robert. Place for a Holiday, The. In: Russell, Leonard (ed.) The Saturday

Book 8th Year. Watford: Hutchinson, 1948.

The White Goddess. London: Faber, 1948.

Graves, Robert and Hogarth, Paul. Majorca Observed. London: Cassell, 1965

Seymour, Miranda. Robert Graves. Life on the Edge. London: Doubleday, 1995

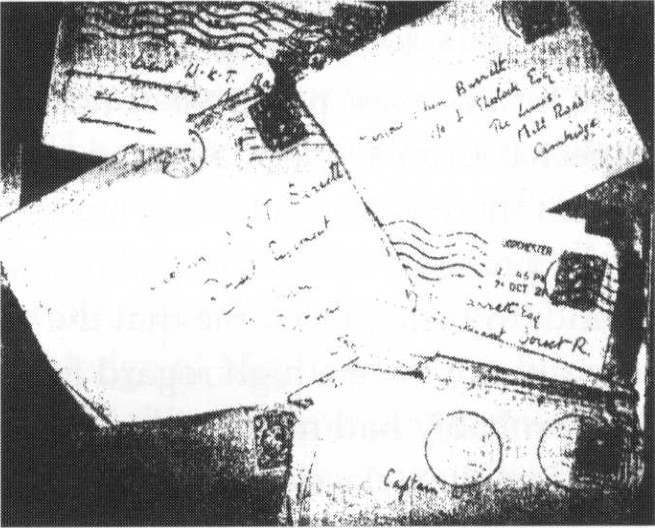

Letters to Ken

from 1917- 1961

A small volume of 37 previously unpublished letters from Robert Graves to Ken

Barrett, a fellow patient at Somerville Hospital during World War I. The letters discuss Graves' first love, marriage, poets and poetry.

Copies may be obtained from Mrs G Doggart, 4 King's Walk, Henley-onThames, Oxon RG9 2DJ at $17 each including post and packaging.