|

Search Help |

|

Links Robert Graves Website Other RG Resources |

Critical Studies

"Sullen Moods": Extant Drafts to Completed Poem

Love, do not count your labour lost

Though I turn sullen, grim, retired

Even at your side; my thought is crossed With fancies by old longings fired.

And when I answer you, some days

Vaguely and wildly, do not fear

That my love walks forbidden ways,

Breaking the ties that hold it here.

If I speak gruffly, this mood is

Mere indignation at my own

Shortcomings, plagues, uncertainties; I forget the gentler tone.

You, now that you have come to be

My one beginning, prime and end,

I count at last as wholly me,

Lover no longer nor yet friend.

Friendship is flattery, though close hid; Must I then flatter my own mind?

And must (which laws of shame forbid)

Blind love of you make self-love blind?

Do not repay me my own coin,

The sharp rebuke, the frown, the groan;

Remind me, rather to disjoin

Your emanations from my own.

Robert Graves wrote "Sullen Moods" in the spring of 1921 when he and his wife Nancy Nicolson were living at Boar's Hill in Oxford. The cottage in which they and their first two children lived was owned by John Masefield and his wife, who were upset when Nancy decided to open a shop on the grounds. The undertaking was a financial failure and, at first glance, seems to have been a most unnecessary distraction for Graves who found himself drawn into the role of shopkeeper, as well as children's nurse, when Nancy was not well. The distractions and irritations were many, understandably causing tensions and, clearly, unpleasant moods. In "Sullen Moods" he apologizes for his unpleasantness, but this seemingly simple poem had much more complex concerns. The drafts of the poem reveal that Graves had very much placed himself under the control of his wife, so much so that in "A Valentine," which also first appeared in Whipperginny (1923), he offered his suicide as homage. He would offer the White Goddess no more. In the poems in this volume, Country Sentiment (1920), and The Pier-Glass (1921), Graves tells of the healing power of his wife's love, as he recovered from the effects of World War I, as he made clear in "Author's Note" to Whipperginny:

The Pier-Glass, a volume which followed Country Sentiment, similarly contains a few pieces continuing the mood of this year, the desire to escape from a painful war neurosis into an Arcadia of amatory fancy, but the prevailing mood of The Pier-Glass is aggressive and disciplinary, under the stress of the same neurosis, rather than escapist. Whipperginny for a while continues so ... (v)

His "amatory fancy" resembles the sentiment found in traditional love poems in the complete devotion of poet/ lover to his beloved; but the beloved is cut from the same pattern as Keats's Merciless Lady. However, Graves's beloved takes command of his body and spirit to heal, not destroy, him.

What seems to be the first draft of "Sullen Moods" was written on an envelope with these words:

Oxford Times 11 rooms

Nice Gardens

Every Convenience

For Sale

Clearly, Nancy had already set him the task of finding a new place to live, and she knew exactly what she wanted as Virginia Woolf recorded Graves explained to her at their first meeting in 1925:

He cooks, his wife cleans; 4 children are brought up in the elementary school; the villagers give them vegetables; they were married in Church; his wife calls herself Nancy Nicholson; won't go to Garsington, said to him I must have a house for nothing; on a river; in a village with a square church tower; near but not on a railway— all of which, as she knows her mind, he procured. Calling herself Nicholson has sorted her friends into sheep and goats. (Conversations, 8)

The cottage was World's End in Islip. Graves may well have been writing out of peake when he put the first words of "Sullen Moods" on the envelope:

Self-love with love of you betwined

And must which laws of shame forbid

These two phrases will essentially inform all drafts of the poem: Graves cannot separate love of himself from love of his wife and is bound by laws other than those of marriage vows. Self-love, as Graves uses the phrase, is amour propre, one's own self-respect. In Graves's case, he can make no separation between his love for his wife and his own sense of worth. "Betwined" perhaps, but without doubt his selflove is dependent on her acceptance.

I assume the drafts to be earliest which are brief, incomplete, and with extensive strikeouts. There are three such drafts, which may well have been written in the order of my discussion. The first is very rough with more words stricken than not. Several clauses, though, emerge as "Help me see you as before;" "When overwhelmed and almost (unreadable) I stumbled on that

The verso of this page has few strikeouts and is in a clearer hand:

"Forgive me, do not think all lost"; "Think it no warning of

At the time, such a breakup is not indicated by any source. They needed money, had a growing family, and were happy. Later Graves's fears would be realized, as he told me when we talked in 1969: "I was a virgin until I was married and never slept with another woman until my wife forced me to. She left with that woman's husband, and I left with that woman". The "woman" was, obviously, Laura Riding, the man Geoffrey Phibbs. Though the two were not married in fact, they were so in Graves's mind. The story of this foursome and their breakup and the consequent injury to Laura Riding is too well known to need repeating here.

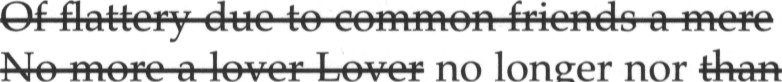

The next draft was written on the verso of a letter (dated 2nd April, 1921) from Holbrook Jackson, editor of To-Day. A Journal of Literature and Ideas, asking Graves for a poem to include in the June issue. Although there are numerous strikeouts and some unreadable words, the concern is clear: Graves believes their love is changing, perhaps into a kind of friendship:

then know that

Since you came to be

Thy whole life's care from start of end

no no

no no

no

longer

no

longer

Friendship is flattery, who could need use

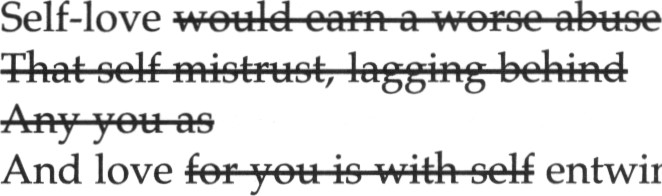

The flatterers art on my his mind will cause a worse abuse

Self love much deception

Self love much deception

Than (unreadable) behind that laying

(Unreadable) do not hurt yourself from me (Unreadable)

And pay me back

I seldom think

Graves used two pens in this draft, suggesting he went back to it. One is very sharp and dark, the other lighter. The last two lines are in the clearer pen. This page provides an early draft for the last two stanzas and makes the connection between the two which Graves did not make when he published the poem: self-love results in the deception of flattery as a way of distancing people from each other; hence disguised moods are flattery (paying undue homage) which he will not do with her, accepting blame for his bad mood. He hopes she will be open with him, not pay him back with flattery. This reading differs from that of the published version, in which he simply asks that she not repeat his mood. Keeping the concern with flattery, Graves wrote: "Must I then flatter my own mind?" Lacking her love, his own selflove would be diminished to friendship, scarcely a condition to provide him with the will to live.

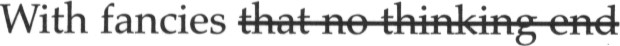

The next draft is on an opened envelope from The Bocardo Press, Oxford, dated 16 April 1921.The half with the address is almost unreadable, though the words "fear" and "alarm" are decipherable. The other half of the page begins:

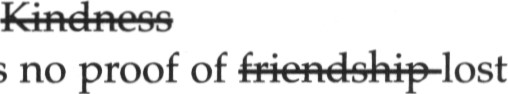

His harshness is no proof of friendship lost

Even in your presence my my

Or if by old fears crossed tired

I answer you sometimes days

I answer you sometimes days

Vaguely and wildly so that you stand

That my love walks in other ways

Forgetting That it What What

Forgetting That it What What

What

What

Tired Grown! With scorn for me

Tired Grown! With scorn for me

Sick For sweetheart long since came to be all

But you have beeeme

Essential Essentially to to me

Such flattery as I give my friends own

Such flattery as I give my friends own

Graves does not enter new material in this draft, but seems to be trying out words, which he will largely, and wisely, reject: "Essential Essentially," "sweetheart" like "Stoutheart" in the previous draft were not retained in the published version. The word "fancies" will be echoed in "Author's Note" to Whipperginny indicating that "Sullen Moods" is one of those "amatory fancies" that helped his recovery from his war neurosis. "Sullen Moods" can be termed a fancy most easily if fancy is thought of as a distraction or illusion, though caprice may be closer to Graves's meaning.

The next draft has one strikeout, and in a clear hand Gives the title and a few phrases:

Sullen Moods

It is no proof

Bound

Blind to the laws that hold it here

Denying home and children here

Denying home and children here

The title and the incomplete sentence appear on the page as if Graves intended a more formal draft of the poem, but he breaks off the draft.

The rest of the page has only two irregularly spaced phrases. Graves may well be again testing words. But the irregular spacing of these phrases and the stricken out "Despising" suggest Graves fell into a deeper and darker mood soon after he began writing the draft. Whatever the case, his withdrawal from "home and children" is the concern of this draft. No more should be made of this, however, than would be of anyone's irritation.

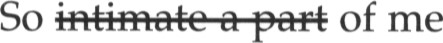

And in the next draft, he completes what he began with the above failed draft, a test version of the poem, close to what will be the published one:

True love

It It

It It

It

is

It

is

That I grow sullen, grim, retired

Even in your presence, my mind crossed

With fancies by old longings fired,

Or that I answer you some days

Vaguely and wildly, so you fear

That my love walks in alien ways

With scorn for what once bound it here.

If I speak harsh this harshness is which indignation with my own Short comings, plagues, infirmities

If I speak harsh this harshness is which indignation with my own Short comings, plagues, infirmities

And I forget to change my tone

For you who long proved to be

For you who long proved to be

My %'ke4e one beginning, prime, and end.

I think of you as wholly me

Lover no longer nor yet friend

Friendship is flattery, wke-eae who could use his own mind?

Friendship is flattery, wke-eae who could use his own mind?

The soothing art

The laws of shame refuse

entwinedentwined

entwinedentwined

entwined

entwined

Hew-t-keR Your self with myself close

*ken do so do not pay me my coin,

With sharp reproof or se44•eR frown or groan,

But my memory to disjoin Your emanation from my own.

But my memory to disjoin Your emanation from my own.

Become once more the distant light

The hope of glory not yet proved Of a perfection wasted quite

Since by such imperfection loved.

Graves signed this draft as he did a very similar one. Most of his changes in the two drafts concern diction. Increasingly, he replaces the flat and prosy and the self-consciously poetic with words that reflect his own poetic language, a heightened poetic one not yet free of the Georgian influence.

In these drafts, however, he wrote a final stanza that he did not retain in the published version:

Be once again the distant light

Promise of glory, not yet known

In full perfection—wasted quite

When on my imperfection thrown.

He retained this stanza in four of the last five drafts, eliminating it only from an incomplete draft. This final stanza is quite remarkable in anticipating what will be his relationship in the future with Woman / Muse / Goddess.

Four of these drafts begin:

Think it no proof of love half-lost

That I grow sullen, grim, retired

Even in your presence, my mind crossed

With fancies by old longings fired

And two of the drafts retain the stanza from a very early draft:

Help me to see you as before

When overwhelmed and dead almost

I stumbled on that secret door

Which saves the live man from the ghost.

This stanza was retained in what I assume was the final draft which began as did the published version:

Love, do not t-ki•Rk count your labour lost

Though I turn sullen, grim, retired

Even at your side; my thought is crossed With fancies by old longings fired.

With the exception of the final stanza, this draft is essentially the same as the published one. Graves did well to eliminate the final stanza with its Victorian, even Tennysonian, resonance. He was at this time still struggling with his father's influence, an influence he credited Edward Marsh with having helped him overcome.

Aside from the final stanza, the most important part of these late drafts is a marginal comment Graves made on what is probably the next to last since it retains the opening: "Think it no proof of love halflost". At the bottom of the page, underneath his signature, Graves wrote in a very clear hand:

Proof of hypnotic not being able to remember original drafts

This statement indicates Graves's understanding of the poetic process as trance-like or dream-like, a belief familiar to those more acquainted with Graves's later writings, those initiated by "The Roebuck in the Thicket," the inspired beginning of The White Goddess. Graves's "Postscript 1960" to The White Goddess explains that his awareness of the Goddess occurred while he was working on The Golden Fleece. He wrote about 70,000 words in three weeks, probably in a near trancelike state (488).

Another similarity between the poem "Sullen Moods" and Graves's later writings, especially those concerned with the Goddess is the utter dependence of Graves as poet (and as man) on the love and will of the woman/ Muse / Goddess. His acceptance of her domination is unreserved as he made clear in both "Sullen Moods" and in "Postscript 1960": "Being in love does not, and should not, blind the poet to the cruel side of woman's nature—and many Muse-poems are written in

helpless attestation of this by men whose love is no longer returned" (491). In "Sullen Moods" Graves had accepted that his love was "no longer returned" and questioned whether friendship could suffice. He seems to conclude his dependence excludes the possibility of friendship.

The major difference between Graves as writer in the twenties to Graves from the thirties (at the latest) on is that he has rejected the information from psychological sources for that from historical and mythological. The reasons for this change are fascinating and will occupy much of the rest of this chapter.

Frank Kersnowski, Trinity University, Texas

WORKS CITED

Graves, Robert. Wipperginny. London: Heinemann, 1923. The White Goddess. London: Faber, 1961.

Kersnowski, Frank (ed). Conversations with Robert Graves. Jackson and London; University Press of Mississippi, 1989.

The drafts of "Sullen Moods" are in the Modern Poetry and Rare Book Collection at the State University of New York at Buffalo and are published here with the Permission of William Graves and the State University of New York at Buffalo.