|

Search Help |

|

Links Robert Graves Website Other RG Resources |

Feature

Donald Davie and Robert Graves: Some Notes and a Letter

Donald Davie, who died in September 1995 aged 73, was one of the foremost poets and critics of his generation. His Purity of Diction in English Verse (1952) and Articulate Energy (1955), both now published together by Penguin, established him as a critic of extraordinary range and clarity of thought. His first collection of poems, Brides of Reason, appeared in 1955, and between them, these three books helped define the critical and poetic stance of what became known as 'The

Movement'. For a while, the 'Movementeer' appellation suited Davie, as it did his friend Thom Gunn, but if Larkin and Amis constituted the group's 'Euro-sceptics', Gunn and Davie surely represented its restless, questing, and ultimately exploratory wing. Ironically, for a poet and critic whose first works were read as the Movement's manifestos, it was Davie who first encountered its criticism for alleged new-fangled modernity. One instance of this criticism can be found in D.J.

Enright's 'Robert Graves and the Decline of Modernism', in which Enright's side-swipes at Davie are framed in the greater context of a discussion of Graves's alleged ascendancy.

Davie's interest in Pound, born out of a need to engage with a poet he at first found disturbing, became a lifelong passion which led him to write several important books on Pound, and groundbreaking articles on a number of Modernist writers. The influence went further than his critical prose: his poetry too began to show a sustained and problematic engagement with writers so far outside the Movement pantheon as to stand in direct opposition to its overt poetic - and implicit political - values.

In 1959, as Davie was reviewing Charles Tomlinson's Seeing is Believing, these issues became clear. The fact that Tomlinson's book was being published in New York, he said, was 'a national disgrace', and he went on to attack

...the silent conspiracy which now unites all the English poets from Robert Graves down to Philip Larkin, and all the critics, editors and publishers too, the conspiracy to pretend that Pound and Eliot never happened. Tomlinson refuses to put the clock back, to pretend that after Pound and Eliot, Marianne Moore and Wallace Stevens have written in English, the English poetic tradition remains unaffected.

Davie's startling association of Graves and Larkin suggests that, to him at least, the 'conspiracy' derived from opposition to a common enemy, rather than from any intrinsic unity of purpose. The climate, it seemed, was one in which the author of The White Goddess and the author of The Whitsun Weddings were on the same side. Tomlinson, Davie goes on

...refuses to honour even the first rule of the club, by sheltering snugly under the skirts of "the genius of the language"; instead he appears to believe, as Pound and Eliot did before him, that a Valéry and a Mallarmé change the landscape of poetry in language other than their own. No wonder he doesn't appeal to our Little Englanders'.

Davie published this in Essays in Criticism in 1959. Interestingly, Graves, in the same journal four years before, had written of exactly the opposite sort of 'conspiracy', one that claimed that the poets Davie mentions were in fact, the only poets worth attending to:

Most of my younger contemporaries have been acquiescing in an organised attempt, by critics, publicists, and educationalists, to curtail their liberty of judgement, and make them bow down before a row of idols

This was first said in the course of one of the Clark Lectures, 'These Be

Your Gods, O Israel', by a poet soon to be elected to the Oxford Professorship of Poetry, defeating in the process F.R. Leavis and Enid Starkie.

Conspiracies and Cross-Purposes

To what extent does this talk of conspiracies help? Not much. On the one hand we have Graves claiming to be the victim of an 'Age of Criticism' which ignored him. On the other hand, we have Davie claiming that the literary climate was, either fearfully or obtusely, ignoring the very poets Graves sees as having been erected as living 'idols', and mentioning Graves, along with his Movement fellow-traveller Larkin, as a prime agent.

The fact that they should both have made these extreme (but not wrong) statements in the same journal is surely perversely emblematic, though not necessarily of clear-cut conspiracies. For in a sense, both are right, though it would take pages to demonstrate the intricacies of why. One could hazard a provisional suggestion, though: Davie the critic is talking about poetry-writing; Graves the poet is talking about poetry criticism. Davie is right to say that the English tradition of poetry writing has, broadly, paid little heed to Pound and Eliot, but Graves is surely right to say that they — and their tradition — had been 'idolised' in poetry criticism. This, at least, is something they're not arguing about, but only because they are, in fact, at crosspurposes.

Davie thought that Graves's high stock in the 1950s and 60s was due to the likes of Enright and Larkin seeking a foil against Modernism (we may recall that Larkin saw Graves's 'crankiness' as an antidote to Modernist 'crankiness'); Graves thought that his own low stock in the same period was due to the likes of Davie promoting Pound and Eliot. It is a peculiar spectacle: Graves and Davie, two eminently successful poets and critics, feeling isolated and marginalised by a so-called 'organised attempt' on the part of mainstream poetry to isolate and ignore them.

Graves on Davie and Davie on Graves

Graves and Davie were involved in what is for us a productive dialogue, though for them it must have counted as more of a sustained disagreement. The following is a partial record of their cross-purposes, and it is produced less for documentary reasons than for what it might tell us about issues of literary-critical history.

Davie sets the ball rolling, in a sense, by referring to Graves in Purity of Diction in English Verse, as a 'minor poet'. He does so in a triply dismissive way: first it is, of course, faint praise; second, it is as one among several 'minor poets' who employ 'impure, eccentric and mannered' diction; and thirdly, the book's apparatus lending a hand, it is a footnote. Davie's condemnation, however, is itself problematic, because it betrays a peculiar openness that precludes the easy invalidation of his criticism: he cites Marianne Moore, John Crowe Ransom and Graves in the list of mannered minor poets. This is a sign of things to come: all three represent vastly different poetic stances. Clearly, Davie's 'agenda' is not defined by 'school', so he cannot claim to be biased on that ground, however much of a critical agenda he undoubtedly has. It seems that it is not enough to be open-minded in one's tastes; the next step is to be so in one's distastes.

Three years later, in Articulate Energy, Davie uses Graves's poem 'Leaving The Rest Unsaid' as an example of 'subjective syntax', poetic syntax perfectly married to '"the form of thought" in the poet's mind'. Graves's poem is 'a tour de force', 'an admirable poem which drives this point home because it pushes this capability of poetic syntax to an extreme'. It was with this poem, in fact, that Davie was to end his reading at the Graves Centenary conference at St John's in August 1995.

These are more or less isolated incidents, and refer so specifically to technical matters (in the non-pejorative sense of the term which both poets respected) that they provide slim pickings for those in search of controversy. Controversy, if, as with the word 'conspiracy', one is prepared to overstate for dramatic effect, begins later.

In 'T.S. Eliot: The End of an Era' (1956), an essay which there is no point in summarising, Davie makes his 'case against "The Dry Salvages"' while at the same time reading Four Quartets as an unsurpassable achievement. Davie's sense of unsurpassable is not awestruck. He means, rather, that it cannot — in the sense also of should not — be surpassed. Davie uses Eliot's poem as evidence of the final 'working through' of what he calls the 'symbolist revolution', but calls for two things: to leave it behind, and a refusal to join 'the conspiracy to pretend that it never happened'.

Already the conspiracy theory has taken shape, and we sense that here too Davie wishes to be pulled in two directions: he hopes for 'a sort of poem more in harmony with the kind of poem written in Europe before symbolism was thought of', while knowing that this sort of poetry, when it comes, will have to understand and know that it has come after what he calls 'symbolism'.

A tall order, given that it requires absolute originality and a sense of tradition, and strangely comparable with Graves's own stance, elaborated at length from A Survey of Modernist Poetry onwards. It is comparable, but not the same, since the very terms at issue — tradition and modernism — are not ready-made tools of expression, but the definitions being fought over. Davie on Eliot is interesting, since this essay (among many others) gives the lie to those — like Graves — who accuse him of idolising Modernist poets. Davie is quite clearly doing something else: he states that the 'End of an Era' clause of his title is in fact written in the 'hope and confidence' that Eliot really is the end of an era. In other words, if the Modernist tradition is to be intelligently absorbed, it needs to be moved on from. This 'moving on', however, is itself only intelligent if it 'looks back'.

Davie is such an exacting and unsimplifying critic that he treats Eliot without a trace of idolatry, as here:

...our confidence in the poet has by this time been so undermined that we cannot, in justice to ourselves, take this as anything but incantatory gibberish. Faced with this, we have to feel a momentary sympathy with the rancour even of a Robert Graves — who, whatever his limitations, would never allow such slapdash inefficiency into his own verses.

Hard criticism this may be (to Gravesians), but it cannot be said that Davie is in awe of Eliot. There is no point worrying about Davie's disrespect: Graves himself was not renowned for the delicacy of his jibes at other poets. Unlike Davie, however, he did not damn them with faint praise: he devoted whole articles and lectures to their merciless pursuit. By 'rancour' Davie must surely have meant Graves's Clark Lectures, given in Cambridge in the academic year 1954-5, in which Graves attacked the 'five idols' of the contemporary canon (Eliot, Pound, Yeats, Auden and Dylan Thomas).

Davie's 'The Poet in the Imaginary Museum', published in The Listener in July 1957, brought out the real tensions in the poetry climate of the time. It was here that the groundwork for a 'dispute' both with Graves and with The Movement was laid. Both aspects of this dispute are captured in D.J. Enright's treatment of Davie in 'Robert Graves and the Decline of Modernism'. In his articles (originally written as broadcasts), Davie says several things that Graves was later to attack in public and in print. Davie argues several points that must have been anathema to Graves and to Gravesians. Here again, there is no sense in summarising Davie, but the closing paragraph of the second part 'The Poet in the Imaginary Museum' is telling:

If I am right, before the imaginary museum situation arose, poems could be complete in themselves, self-dependent, cut loose from the poet who wrote them, in a way no modern poem can be. That sort of pleasure can be afforded by modern poems only when they are minor, even provincial achievements. I have sympathy with those poets (such as Robert Graves, I suspect) who care so much for this kind of poetic pleasure that they choose to write minor poems possessing it, rather than major poems which must do without it; and equally I sympathise with those modern readers who for the same reason would rather read the minor poems of our age than the major ones.

Despite the fact that Graves has 'taken abundant note of modern anthropological researches', Davie places him alongside Frazer as representative of an older school of anthropologists intent on discovering 'one or two archetypal patterns underlying apparent cultural diversity'. Here too Davie applies an important distinction, by saying that modern anthropology insists 'on a diversity, which is irreducible, of any number of culture-patterns each of them sui generis', and by implication calling into question the validity of The White Goddess. There is, as is becoming clear, very little common ground between Davie and Graves, and what began as 'technical' matters — Davie's allusion to cramped and mannered diction — has now developed into irreconcilable differences of first principles. This should not obscure the fact that Davie's assessment of Graves is based, if not sympathetic reading, then at least on a clear awareness of the issues raised by his work. Graves is at once 'traditional', in the sense of refusing to allow for Modernism's having changed the poetic landscape, and peculiarly beholden to a brand of mystical anthropology that takes him too far outside 'Tradition' to be easily categorised. Davie will return to this question in his 1960 review of Graves's Collected Poems.

Meanwhile, Graves does not take Davie's 'Imaginary Museum' argument kindly. In 'The Making and Marketing of Poetry', published in October 1958 as 'The American Poet as Businessman', he addresses it face-on:

The latest pronouncement I have read on the subject of the creative writer's dilemma was made by Dr Donald Davie, a British critic. [...] If I have understood Dr Davie's argument, the exhibits from the imaginary museum which [poets] borrow and work into their poems must necessarily remain undigested. Thus Yeats did not really go Japanese in his Noh play imitations; or Pound, Chinese in his sinophilic Cantos; or Eliot, Indian in his brief bout of Buddhism at the close of The Waste Land.

One might protest, at this point, that yes, this is exactly what Davie is saying: that Japanese, Chinese and Buddhist elements are not digested and seamlessly 'worked into' the work of these poets, and that their poetry functions on precisely that basis. Graves goes on:

Dr Davie holds that all contemporary English poets fail to be major, by not realizing how important it is to keep one foot in, and one foot out, of the imaginary museum — they have never ventured across the threshold, he says, and therefore remain provincials. He adds that, on the contrary, too many American poets make themselves too much at home in the museum galleries

The words 'failing to be major' and 'provincial', are of course, recognizable as coming from Davie, and Graves then quotes the passages from 'The Poet in The Imaginary Museum' in which he is mentioned as a poet who commits both errors. In fact, it may be only one error, but one that comes in two parts: first one is 'provincial', then 'one 'fails to be major'. Graves then makes an interesting statement, which perhaps has in its sights the poetry of the 1950s, and more specifically that of The Movement:

An ugly feature of the imaginary museum situation, which major critics have forced upon us, is that the sturdy provincials, American or English, who react against it, are also tempted to react against the ancient English tradition to which they are the fortunate heirs. They may be rightly vexed that in this age of drawing-room charades — of 'pastiche and parody' — certain major poets have used Tudor and Jacobean poetry as a sort of dressing-up trunk to be hauled down from the attic to supplement their Noh masks, Chinese brocades and troubadour lutes. But that is no reason for throwing it out.

Perhaps Graves is here thinking of what Blake Morrison called The Movement's 'failure of nerve', its self-conscious appeal to 'middlebrow' insularity, an insularity that was not cultural this time, but literary-historical, which avoided risks and remained defensively 'contemporary' at the cost of ignoring and ridiculing its own past. Perhaps Graves is complaining that the unbridled adulation of Modernists had provoked an equally unbridled suspicion of the more ambitious elements of the 'native tradition'. Certainly The Movement was 'antiromantic', and in its desire to avoid all traces of romanticism disdained as much 'English' poetry as it did European or American. For Graves, Pound and Eliot and their like were disastrous not simply because of their impact on their admirers, but because of the extreme reaction they provoked in their detractors. Unthinking devotion to

Dr Davie holds that all contemporary English poets fail to be major, by not realizing how important it is to keep one foot in, and one foot out, of the imaginary museum — they have never ventured across the threshold, he says, and therefore remain provincials. He adds that, on the contrary, too many American poets make themselves too much at home in the museum galleries

The words 'failing to be major' and 'provincial', are of course, recognizable as coming from Davie, and Graves then quotes the passages from 'The Poet in The Imaginary Museum' in which he is mentioned as a poet who commits both errors. In fact, it may be only one error, but one that comes in two parts: first one is 'provincial', then 'one 'fails to be major'. Graves then makes an interesting statement, which perhaps has in its sights the poetry of the 1950s, and more specifically that of The Movement:

An ugly feature of the imaginary museum situation, which major critics have forced upon us, is that the sturdy provincials, American or English, who react against it, are also tempted to react against the ancient English tradition to which they are the fortunate heirs. They may be rightly vexed that in this age of drawing-room charades — of 'pastiche and parody' — certain major poets have used Tudor and Jacobean poetry as a sort of dressing-up trunk to be hauled down from the attic to supplement their Noh masks, Chinese brocades and troubadour lutes. But that is no reason for throwing it out.

Perhaps Graves is here thinking of what Blake Morrison called The Movemen€s 'failure of nerve', its self-conscious appeal to 'middlebrow' insularity, an insularity that was not cultural this time, but literary-historical, which avoided risks and remained defensively 'contemporary' at the cost of ignoring and ridiculing its own past. Perhaps Graves is complaining that the unbridled adulation of Modernists had provoked an equally unbridled suspicion of the more ambitious elements of the 'native tradition'. Certainly The Movement was 'antiromantic', and in its desire to avoid all traces of romanticism disdained as much 'English' poetry as it did European or American. For Graves, Pound and Eliot and their like were disastrous not simply because of their impact on their admirers, but because of the extreme reaction they provoked in their detractors. Unthinking devotion to

Davie entitles his review 'Impersonal and Emblematic', and suggests that Graves's gifts as a poet lie in his capacity to write 'emblematic' as opposed to 'symbolic' - poetry in an age where, rightly or wrongly, 'symbol has been most practised and most highly esteemed'. Davie is emphatic that the one is not inferior to the other, and his praise for Graves's 'achievement' is qualified but sure. The point Davie makes about Graves's place alongside Pound, Auden, Thomas and Eliot is important: how will the he be perceived in the future, in 1998 for instance? Will the literary historian place Graves among those poets who, like Eliot, Pound, Auden and Thomas, actually alter the way poetry is being written, as they indisputably have, or at least for a while did? Will literary history be able to 'place' him by following the reverberations of his poetry along definable movements in English poetry? Davie does not, we notice, ask how Graves will 'rank', but how he 'fits in', implying that there has to be something to 'fit into', that there has to be a context, even if that context turns out to be of the poet's own making. But Davie withdraws from the question as soon as he raises it: 'because it prejudges the issue', so we are left where we started.

The clue comes in Davie's first paragraph, in which he notes Graves's 'self-consciously independent' front and his 'self-imposed exile'. These are references to Graves's persona, granted (and Davie's article goes on to compare Graves with Yeats in a way that would have greatly displeased Graves), but they might help us to speculate usefully about Graves's 'situation'. The four poets Davie invokes have been deeply influential, and they have done so by, broadly speaking and in different ways, disrupting the traditions which they inherited. But they also, more importantly, had contexts: their poetries have contexts, but they were all, in their way, also creators of their contexts. Perhaps we could even grasp the nettle and say that they created for themselves more context than they did tradition. Beside them, Graves seems almost bereft of context, all the while being manifestly more 'traditional'. Certainly, to the late twentieth-century, a 'context' for Graves is altogether harder to find than the tradition which produced him.

To go back to the 'Imaginary Museum' theory, which I think raises without explicitly stating this problem, the simultaneous availability of a multitude of 'traditions' (linguistic, cultural national) necessarily comes at the cost of 'context'. At the risk of sounding 'postmodern', it is perhaps the case that such ease of access to traditions precludes any stabilising context, and that the 'Imaginary Museum' is a place where the link between traditions and their contexts have been broken. It may be reading too much into Davie's point about 'fitting in', but the phrase, side-stepping value-judgements as it does, pushes one to look elsewhere for a respectable means of addressing such issues. If the word 'tradition' is, as we suggested earlier, not a tool of expression but part of what needs to be expressed, then the idea of a 'context', especially when it is posited as something that can come after rather than merely before or during, a particular poet's work, looks likely to help (a little) with Graves. It might also help with Pound and Eliot and Auden. When Graves asserts in the foreword to his Collected Poems that he is part of the 'Anglo-Irish tradition into which [he] was born', and at the same time devotes so much space to attacking his contemporaries, we might legitimately wonder whether Graves too does not see this: he is comfortable with his 'tradition', but knows that he cannot be comfortable with his context.

A Letter from Donald Davie

Davie was one of the first English critics, and one of the earliest

English poets, to recognise the American poets Charles Olson, Louis Zukovsky, George Oppen and others. These are poets England still has difficulty with, but Davie's difficulties were productive, enlightening, managing to keep hold both of what he objected to and what made his objections surmountable. His 'Recollections of George Oppen in a Letter to an English Friend' is a masterpiece of recalcitrantly 'difficult' mourning and resisted sentiment:

Pathfinder, though? Trailblazer? Never for me, threading the roaring dells and snapping branches of morose inspirations, aspirations, habits held up to the weak light, scowled at. Not a bit of help to me was George, or George's writing: though he achieved his startling poignancies, I distrusted them, distrust them still.

Perhaps this, in caricature, captures part of Davie the critic, as well as Davie the poet: an English temperament, temperamentally both open and resistant, distrustful and committed. With Pound, with Oppen, with the Black Mountain poets, indeed with any form or idea with which he engages, Davie is so far centred in his reasons for resisting it that his qualified accession to it (if and when it comes) seems all the more spectacular and truthful. Many of Davie's poems are about resistance, about knowing that life is too complicated for contradictions ever to be resolved into anything other than dilemmas:

How else explain this bloody-minded bent

To kick against the prickings of the norm;

When to conform is easy, to dissent;

And when it is most difficult, conform

('The Nonconformist')

Davie's last poetry reading, and his first for some years, was at the

Graves Centenary Conference at St John's College, Oxford, in August 1995. He shared the platform with Seamus Heaney and James Fenton, and gave a spirited and perfectly-judged reading. We had begun a correspondence a few months earlier, and a few weeks before he came to Oxford, I wrote to ask him how, in 1995, he felt about Graves. Here is a relevant extract from his scrupulous and informative reply:

As for the more urgent matter of how Robert Graves figured for the English poets of the 1950s ... I fear I can supply only Dead-Sea fruit. Graves's claim on us was one of the shamelessly many matters on which The Movement refused to accept responsibility. I seem to have written an approving review called 'Impersonal and

Emblematic', and also a broadcast on 'The Toneless Voice of Robert Graves'. But in those pieces I spoke only for myself, not for the group of us. Nor did I persist for long. For the Gravesians were not in a mood to receive any olive-branches. The Movement, so far as it represented a socio-political shift, was 'anti-Romantic', whereas Graves and the Gravesians were, in their own quite special understanding of the matter, unashamedly and even belligerently 'Romantic'. Graves's Clark Lectures, The Crowning Privilege, made it clear, if anyone had doubted, that the issue was non-negotiable. A great pity — opposing stances in (not literary theory but) literary history made it impossible for us to acknowledge what we (I, at any rate) owed to Graves as an exemplar in the building of lyric stanzas.

As no doubt you are aware, the Gravesians survive among us; and some of them are influential, like Robert Nye, who has pontificated about poetry in The Times for 30 years, and the more flamboyant Martin Seymour-Smith, who ten years before that was the man I had in my sights in my 'Rejoinder to a Critic'. The nicest and most honourable of them was the late James Reeves, who was my valued friend; but my affection for him could not get round the fact that he wrote a book rabidly assailing Alexander Pope as the type of the anti-poet. I think that is telling: 'romantic' is what I have called them, and what they proudly call themselves, but in many ways (e.g. about Pope) it would be more accurate to describe them as unreconstructed Victorians. None of us in the Movement could fail to discern that, and to keep our distance from it.

In short, though some of the Movementeers (e.g. Amis, Larkin) chose to posture at times as anti-Modernists, the alternative to modernism that Graves and the Gravesians offered was not to our liking at all — it was altogether too 'unsmart' and fusty; to give us a little more credit, Auden had entered our bloodstream, whereas Gravesians wouldn't give him the time of day.

There remains what I've called 'the building of lyric stanzas'. The man had opinions that couldn't be taken seriously; on the other hand at his best he could be a model of how to manage syntax across rhymes and line-endings. It's my grateful sense of that which made me happy to accept the invitation to read some of his poems in Oxford.

I don't think my attitude to Graves has changed essentially since the 1950s. He was in many ways a monumentally silly man; but when he wasn't peddling opinions, he had a lovely ear and an enviable command of the varieties of English diction. It occurs to me that I feel rather similarly about our current Poet Laureate.

I hope this helps, a little.

His letter is characteristically informative and precise, and it lacks any note either of bardolatry or regret. He knows both what he admires and what he does not in Graves's work.

We are, it seems, more or less back where we started. Among the poems that Davie read at the Graves Centenary Conference was

'Leaving the Rest Unsaid', the tour de force which he had cited entire in

Articulate Energy in 1955. On the day he arrived, as we were drinking in the Eagle and Child, he said how pleased he was to be invited to the Graves conference. He then told me: 'Graves is far too important to be left to his admirers'.

Patrick McGuinness, Jesus College, Oxford

THE WILFRED OWEN SOCIETY

"My subject is War, and the pity of War. The Poetry is in the pity All a poet can do today is warn."

The Wilfred Owen Association was formed in 1989 to commemorate the life and work of the renowned poet who died in the final week of the First World War.

Philip Larkin described him as "an original and Unforgettable poet'?} "the spokesman of a deep and unaffected compassion".

Owen's poetry retains its relevance and universal appeal; it is certainly much more widely read and appreciated now than at any time since his death.

In 1993, the Centenary of Owen's birth, and the 75th anniversary of his death, the Association established permanent public memorials in Shrewsbury and Oswestry and organised a series of publiC commemorative events.

The Association publishes a regular newsletter and promotes readings, talks and performances. It promotes and encourages exhibitions and conferences, and awareness and appreciation of all aspects of

Owen's poetry. It also intends to establish a commemorative fund to promote poetry in the spirit of Wilfred Owen,

For more information please write to:

The Membership Secretary,

17 Belmont, Shrewsbury SYI ITE, UK

GARCANET

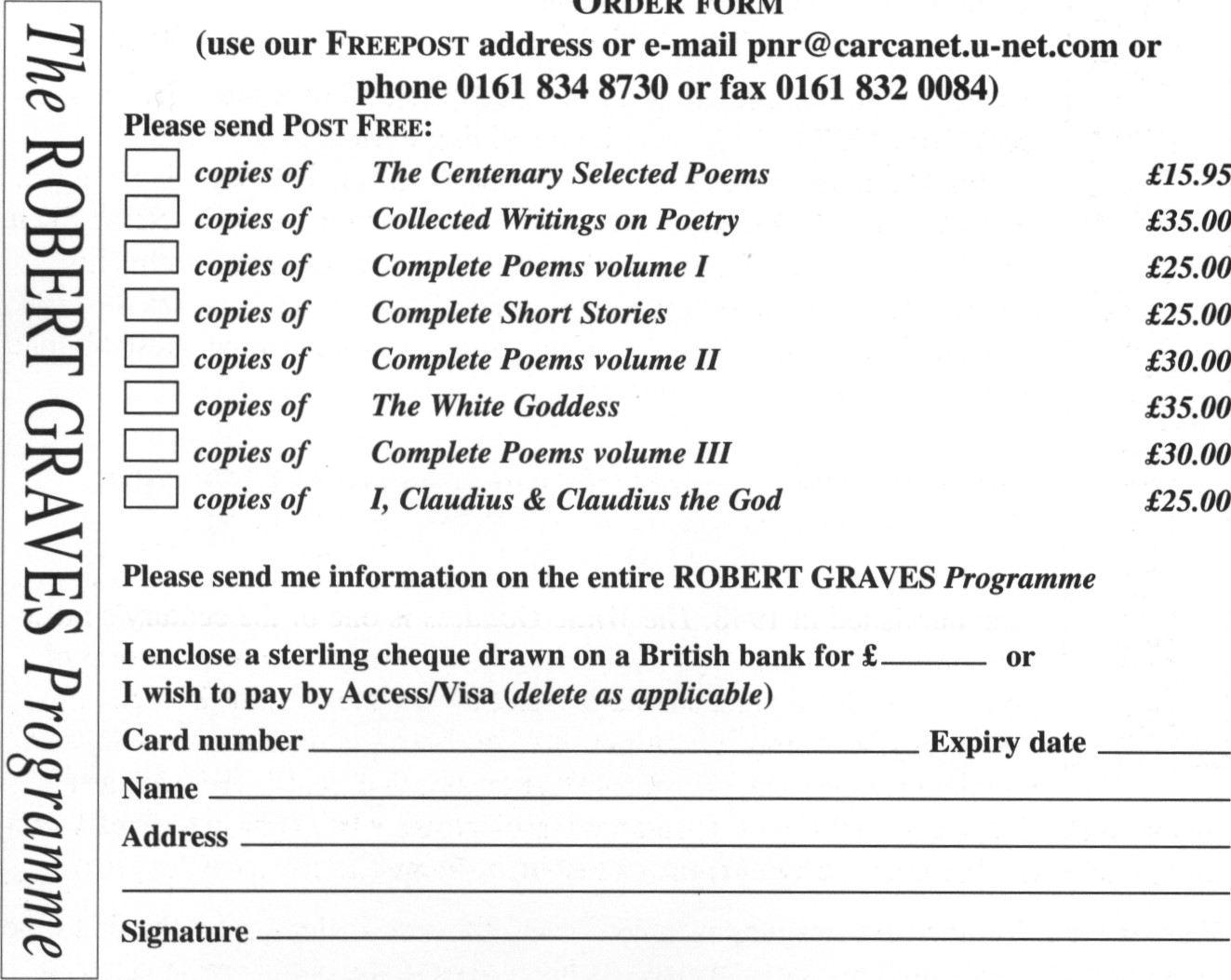

In 1995, the centenary of the poet's birth, Carcanet launched The ROBERT GRAVES Programme which, over the next decade, will bring into print the bulk of Graves's writings in verse and prose in new editions with introductions by poets, scholars and other authorities. 22 volumes are currently projected.

General Editor Patrick Quinn

Professor of English at Nene College, University of Northampton, Patrick

Quinn is the author of a study of the writing of Graves and Siegfried Sassoon, The Great War and the Missing Muse (AUP, 1993) and the edited study of British writers of the 1930s entitled Recharting the Thirties (AUP, 1996). He is the editor of Gravesiana: The Journal of the Robert Graves Society, a biennial journal dedicated to Graves studies.

AUGUST 1997 PUBLICATIONS

Complete Poems Volume 11 edited by Beryl Graves and Dunstan Ward

In this second volume of the Complete Poems, all of Robert Graves's work from 1927 to 1942 - the Laura Riding Period, as series editor Patrick Quinn describes it in the Centenary Selected Poems - is included.

'The Cool Web', 'Flying Crooked', 'Down Wanton Down!' , 'Never Such Love', 'Danegeld', 'Parent to Children' and other favourite anthology pieces date from this rich period in which Robert Graves makes the astonishing transition from his early work and becomes incontestably one of the great lyric poets in our literature.

The White Goddess - an historical grammar ofpoetic myth edited with an introduction and additional material by Grevel Lindop

First published in 1948, The White Goddess is one of the century's most extraordinary books. A poet's impassioned introduction to the world of poetry, it is also a great scholar's quest for the meaning of European mythology, a polemic about the relations between man and woman, and an intensely personal document. It stands beside Yeats's A Vision as a major work of modern myth-making, and the clarifications it wrought in Graves's own mind made possible the writing of some of his finest poems.

This new edition incorporates major corrections to the text, including for the first time all Robert Graves's final revisions, as well as his replies to the book's reviewers and his own account of the months of inspiration in which The White Goddess was written.

MAY 1998 PUBLICATIONS

Complete Poems Volume 111 edited by Beryl Graves and Dunstan Ward ISBN 1 85754 2800 352 PP €30.00 HB After Laura Riding had parted company with him in 1942, Robert Graves moved into a new and decisive phase in his work, producing the White Goddess and Black Goddess poems. This final volume of the Complete Poems brings together the last three decades of the poet's work including many previously uncollected poems.

I, Claudius and Claudius the God edited with an introduction by Richard Francis ISBN 1 85754 2797 356 €25.00 1--1B

I, Claudius and Claudius the God depict one of the strangest and most terrifying epochs in the history of

Europe, as the Roman empire fell into the hands of cruel, mad, incompetent emporers: Tiberius, Caligula. Nero. These shocking and yet oddly comic novels depict the licentiousness and rapacity that triggered the power struggles of ancient Rome. Published in 1934 as dark clouds once more gathered over the western world, they dramatise the always unresolved struggle between anarchy and social order, and in doing so explore the strength and limitations of the values of decency and reason when confronted by evil.

PUBLISHED VOLUMES

The Centenary Selected Poems (1995)

edited by Patrick Quinn

Complete Poems Volume I (1995)

ISBN 1 85754 126 X

160 PP

€15.95 HB

edited by Beryl Graves and Dunstan Ward Collected Writings on Poetry (1995

ISBN 1 85754 171 5

448 pp

25.00 HB

edited by Paul O'Prey

Complete Short Stories (1995)

ISBN 1 85754 172 3

577 PP

€35.00 HB

edited by Lucia Graves

ISBN 1 85754 131 6

340 PP

€25.00 1--1B

ORDER ORDER

ORDER ORDER

ORDER

FORM

ORDER

FORM

Send to our FREEPOST address

Carcanet Press, FREEPOST MR6474, Manchester M3 9AA